We’ve made the society pages! No, not those society pages. These ones.

We’ve made the society pages! No, not those society pages. These ones.

For those of you know us already, the only thing that’s different, really, is our url. Our content will remain unchanged. For those who are meeting us for the first time, allow us to introduce ourselves—and what we’re doing here.

Girl w/Pen is a group blog dedicated to bridging feminist research and popular reality. We publicly and passionately dispels modern myths concerning gender, encouraging other feminist scholars, writers, and thinkers to do the same. We’re a collective of feminist academics, crossover writers, and writers who have left the academy to pursue other thought leadership forums and forms.

Like researchers and writers themselves, blogs grow up, evolve, and shift shapes. Such has been the story of Girl w/Pen, which began in 2007 as a way for me to keep friends and family posted as I hit the road on book tour. The name, Girl w/Pen, came in a flash, an easy way to describe myself at the time—an academic transitioning to an identity as a writer in a different realm.

Girl quickly became girls (I know, I know, women—but it was the youthful blogosphere, right?). When I started giving workshops on translating academic ideas for trade, participants of my seminars contributed guest posts. Some became regulars. Other fellow travelers followed suit, coming in and out as interests and workflow allowed. In 2009, we decided to turn GWP into a full-fledged group blog, with a full roster of columns, and the name stuck. Though admittedly anachronistic, our name continues to speak to the writerly journey many of us have taken, are on, and aspire to, as we put our thoughts to metaphorical paper, raise our collective voices, experiment, bridge research and reality, rabble rouse, and inform.

GWP has become a true interdisciplinary forum, enriched by its range. Our current lineup of columns includes:

Bedside Manners (Adina Nack): applying the sociological imagination to medical topics, with a special focus on sexual and reproductive health

Body Language (Alison Piepmeier): Because control of our bodies is central to feminism. (“It is very little to me to have the right to vote, to own property, etc., if I may not keep my body, and its uses, in my absolute right.” –Lucy Stone, 1855)

Body Politic (Kyla Bender-Baird and Avory Faucette): A co-authored column on queer bodies, law, and policy.

Girl Talk (Allison Kimmich): truths and fictions about girl

Mama w/Pen (Deborah Siegel): reflections on motherhood, feminist and otherwise

Nice Work (Virginia Rutter): social science in the real world

Off the Shelf (Elline Lipkin): book reviews and news

Second Look (Susan Bailey): a column on where we’ve been and where we need to go

Science Grrl (Veronica Arreola): the latest research and press on girls and women in science & engineering

Women Across Borders (Heather Hewett): A transnational perspective on women & girls

We’re delighted to be teaming up with The Society Pages, where we join an active and far-reaching multidisciplinary blogging community, supported by publishing partner W.W. Norton. When we first started looking for a home, TSP was the first that came to mind. Major props to Adina Nack for suggesting it, Virginia Rutter and Heather Hewett for seeing it, Lisa Wade and Letta Page for brokering it, Jon Smajda and Kyla Bender-Baird for so beautifully executing it, and Doug Hartmann and Chris Uggen for having the vision in the first place—and for welcoming us in.

Here in our new neighborhood, you’ll find long-established and esteemed blog neighbors like Sociological Images, Thick Culture, and Sexuality and Society—blogs that in many ways share our DNA. You’ll also find here roundtables, white papers, teaching resources, and Contexts magazine. Everyone here is invested in bringing academically-informed ideas to a broad public, to speaking about society with society—just like we’ve always been.

Those of us thinking in public about the way feminist research informs our surroundings and shapes our world look forward to settling into our new digs. As ever, we invite you to join us. We welcome your comments and critiques, your follows (@girlwpen) and your shares. We welcome pitches for guest posts. We’ll keep evolving, enriched by our TSP neighbors, and by you.

We’re honored to be here, and to be a part of your society. Please don’t hesitate to get in touch, and let us know what you think.

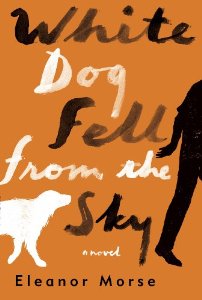

In yesterday’s issue of The Washington Post, I review White Dog Fell from the Sky, a new novel about an unlikely friendship between an American expat and a South African refugee (“Eleanor Morse’s White Dog Fell from the Sky”).

In yesterday’s issue of The Washington Post, I review White Dog Fell from the Sky, a new novel about an unlikely friendship between an American expat and a South African refugee (“Eleanor Morse’s White Dog Fell from the Sky”).

![High Society by jesuscm [on/off]](http://farm7.staticflickr.com/6152/6251499620_dab1f2b75c.jpg)

You heard about the letter: Princeton alumna Susan Patton

You heard about the letter: Princeton alumna Susan Patton  The folding of

The folding of  Earlier this month I wrote about

Earlier this month I wrote about