When men have children they start earning more—it’s the “daddy bonus.” The size of the bonus? About 11 percent of average earnings across a wide variety of educational, racial and ethnic characteristics. It begs some good questions, and sociologists Melissa Hodges and Michelle Budig at UMass Amherst have answered a lot of them in their recent Gender & Society article, “Who Gets the Daddy Bonus? Organizational Hegemonic Masculinity and the Impact of Fatherhood on Earnings” (abstract).

For example, you might ask, is the daddy bonus because men who are better at earning are also more likely to have kids? This is called the selection hypothesis, and Hodges and Budig’s analysis says “no.” In fact, having children creates a reversal of fortunes, a case of “negative selection.” The dudes who have kids have characteristics that suggest lower earning, not higher earning. But they end up turning it around when the babies arrive.

Is it because dads start to work more? When men become fathers they do work more. But that doesn’t produce the daddy bonus. Instead, the authors found that being married to a woman (a marriage bonus) accounted for about one-half of the increased earnings. Unmarried dads? No daddy bonus.

Is it because dads benefit from the breadwiner/caregiver model? Research sometimes shows that when wives de-emphasize market work (part time work or staying home) this is associated with men’s higher earnings (you can see a case of it here). Not so for whites and African Americans in this study, though it was true for Latinos. The “marriage bonus” for all groups, however, may relate to having the benefits of the extra share of domestic work that wives tend to do regardless of labor market participation.

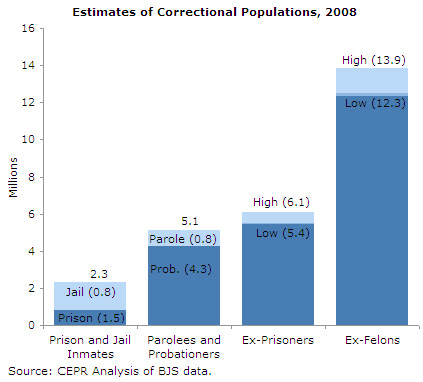

Does everyone get the daddy bonus? Yes and no. All fathers, regardless of race and ethnicity, gain a wage advantage. But look at this: white dads received an 8.3 percent bonus, black dads a 7.3 percent bonus, and Latino dads a 9.2 percent bonus.

The authors explain: “Most men experience gendered advantages in the labor market, but not all men are equally privileged…. Men’s ability to capture the ‘patriarchal dividend’–privileges and rewards accruing to men by virtue of living in a gender-unequal society–varies by their other status characteristics….” What they are talking about is “hegemonic masculinity.” Think of it as the “war within the sexes” – you can read more about it here.

Hegemonic masculinity is a big term for a concept that we all know intuitively: that being a good man gets blended together with other cultural norms to amplify male privilege for some men more than others. As Joan Williams has explained so well, we think the “ideal worker” (you can find a discussion of here) is gender neutral. But work is organized so that people who don’t have competing responsibilities–for example, for the kids–fit in better than people who have work-family conflicts. And those people, overwhelmingly (though not always) are men. Indeed, many of the cultural norms relate to work, others relate to heterosexuality. The effect is that it just seems obvious who has “earned” their rewards.

Hodges and Budig found that the fatherhood bonus is bigger for white men in professional/managerial positions, for white men and Latinos with college degrees, white men in occupations that emphasized mental activity more than physical activity, white men and Latinos in jobs that de-emphasized strength, and (as mentioned above) Latino men with more economically dependent spouses.

So, all men benefit from college education (though the benefits aren’t so great for everybody, as you can read here), and all men benefit from fatherhood. But fatherhood benefits for college educated white men is about 21 percent, Latino men 19 percent, and African American men is 7.3 percent (no different from the benefit for non-college educated African American dads).

The authors sum it up: “…the effect of becoming a father is another source of privilege for privileged men, but less so for men who are in more socially disadvantaged positions.” So, if you were looking for an example of “hegemonic masculinity,” now you have one.

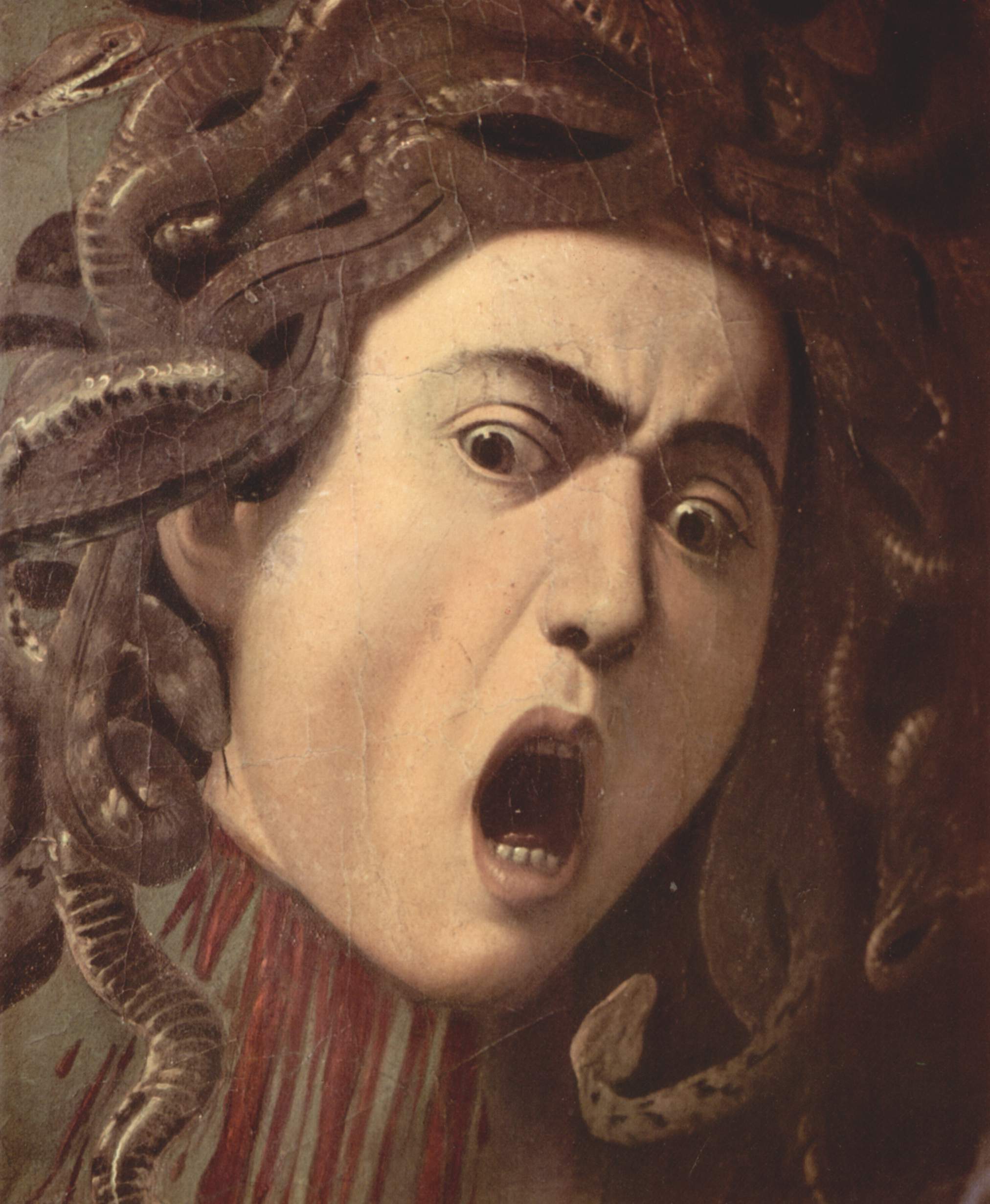

Bridgette A. Sheridan

Bridgette A. Sheridan

Here’s something we don’t need a piece of research to tell us (though I’m going to tell you about a really good example): men with MBAs earn a lot more than women with MBAs. Most of the gap is explained by having children – which costs women but not men. Most of that parental-status tax costs women because they have to give up time at the office.

Here’s something we don’t need a piece of research to tell us (though I’m going to tell you about a really good example): men with MBAs earn a lot more than women with MBAs. Most of the gap is explained by having children – which costs women but not men. Most of that parental-status tax costs women because they have to give up time at the office. Jeeze. Just read

Jeeze. Just read  Here’s how it works: if you call it a “diversity initiative” or a “work family intervention” or stuff like that there’s the chance that you will see resistance to the project of, well, promoting diversity, or creating a family-friendly work place. On campuses, all the earnest and the marginalized check it out and everyone else goes, “what? Oh, I don’t think I got that email.”

Here’s how it works: if you call it a “diversity initiative” or a “work family intervention” or stuff like that there’s the chance that you will see resistance to the project of, well, promoting diversity, or creating a family-friendly work place. On campuses, all the earnest and the marginalized check it out and everyone else goes, “what? Oh, I don’t think I got that email.” Heard from

Heard from