This month’s guest column* by Tristan Bridges, Ph.D., deals with a recent research publication on a correlation between testicle size and nurturing instincts/behaviors in men. Bridges, a sociologist at The College at Brockport, State University of New York, is currently working on a project dealing with the meanings of “man caves” in contemporary U.S. households.

__________

So…I’m going to go ahead and say that this is the wrong question to be asking. This question proceeds from a belief that testicles CAN tell us something about dads. A new study is making the rounds in the news that addresses the relationship between testicle size and parenting behavior among men (well… 70 men… not randomly sampled…). The paper is entitled “Testicular Volume is Inversely Correlated with Nurturing-Related Brain Activity in Human Fathers” in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. I can think of more than a few titles that might have been catchier (and clearly, journalists reporting on the research had a similar idea).

In fairness, I don’t have access to the complete study (though I’ve requested it). But the problem is also in how this study gains attention in the media. It’s a great example of how a correlation combined with cultural stereotypes and assumptions can run wild. When correlations combine with popular stereotypes concerning a particular topic (like, say, the relationship between testosterone and any number of socially undesirable behaviors), questions about the science sometimes get lost because it looks like something was “scientifically proven” that we already wanted to believe anyway.

In fairness, I don’t have access to the complete study (though I’ve requested it). But the problem is also in how this study gains attention in the media. It’s a great example of how a correlation combined with cultural stereotypes and assumptions can run wild. When correlations combine with popular stereotypes concerning a particular topic (like, say, the relationship between testosterone and any number of socially undesirable behaviors), questions about the science sometimes get lost because it looks like something was “scientifically proven” that we already wanted to believe anyway.

So, here’s the relationship the researchers found: men with smaller testicles tested more positively for nurturance-related responses in their brains when shown pictures of their children. The study reports that men with smaller testicles had roughly three times the level of brain activity in the area of the brain associated with nurturing. These men (with smaller testicles) were also men with lower levels of testosterone—something that has previously been shown to be associated with nurturing behavior among men.*

Side Note: Just for fun, I’d love to know how to measure testicular size. Is it a measure of circumference (in which case I’d want to know: width or height)? Is it a measure of total tissue volume? And, how is the measurement taken? There’s probably a great “How many grad students does it take to….?” joke in here somewhere. But, I’ll rise above the temptation.

The researchers, then, have found a correlation between nurturing-related brain activity and testicular volume (and, to be fair, this is right in their title). But, off the top of my head, I can think of more than a few ways of explaining this correlation differently than they have. And, if you’re not up on your research methods, a correlation simply means that two (or more) trends, variables, etc. can be shown to vary together. So, age an income might be an example. But proving that one variable or trend is actually causing another is more difficult. To prove a causal relationship, you need three things (to convince the scientists anyway):

- Correlation—you’ve got to be able to show that the two things you’re saying have a relationship actually have a relationship with one another.

- Time Order—you’ve got to be able to show that the thing you’re saying is “causing” the other thing happens prior to the change you’re claiming is “caused.”

- Rule Out Other Possible Explanations—even when you’ve established a correlation and can show time order in a way that favors your interpretation of the relationship, you still have to consider alternative ways of explaining the same finding.

Okay, back to the testicles. So, the study shows a correlation. And, there are really three explanations for the correlation. Either: a. testicle size is causing (or inhibiting) nurturance, b. nurturing behavior (or lack thereof) is causing testicular volume, or c. something else is to blame for both nurturing behavior and testicular volume.

Stanford neuroendocrinologist Robert Sapolsky wrote a great essay on the relationship between testosterone and violence. Sapolsky argues that there is a huge cultural bias favoring an understanding wherein higher levels of testosterone are seen as responsible for increased violence (especially in men). But, research actually favors the opposite understanding: violence causes spikes in testosterone levels (see, time order really is important). My sense is that a similar misstep is taking place in the debates about testicular volume, testosterone and nurturing behavior among men.

The authors of the testicular volume study are upfront in claiming that they are unable to actually demonstrate that testicular size is a “cause or a consequence of male life-history strategies”. However, like the relationship between testosterone and violence, they have cultural bias on their side in suggesting the relationship is causal. Cultural stereotypes surrounding testosterone create an environment in which testicle size (and associated levels of testosterone) are much more likely to be framed as the culprit.

So, a possible interpretation of this study (and the one that the media has been quick to adopt) is that some men seem biologically better suited to be fathers—to actually participate in nurturing and caregiving. But, a more complex implication could be that caregiving and nurturance are not qualities for which people are more or less biologically suited. Engagement in nurturing and caregiving behaviors causes changes in both women and men—emotional, behavioral, and, yes, physiological as well. If I had to guess what the actual relationship is between testicular volume and nurturance, I’d guess that testicular volume is a consequence, not a cause, of nurturance among men. While they haven’t proven causation, this is, biologically speaking, the interpretation with more evidence.

Why does this matter? In a culture in which women are culturally understood as responsible for the caregiving of children, it’s easy to assume that women’s nurturing qualities are somehow hardwired. Similarly, in a cultural environment in which men have (in recent history) done relatively little caregiving, it might be easy to similarly assume that they are somehow naturally ill-suited to nurture. Correlations like this let men off the hook for being bad parents. It sounds like they can’t help it. But, there are plenty of factors that work against men’s active involvement in their children’s lives in the U.S. today. They just aren’t biological.

*To be fair, this study is longitudinal and does acknowledge time order. What’s problematic is the assumption that parenting activity is the only behavior that might have this effect on men’s testosterone levels, as well as the assumption that men’s testosterone levels are naturally high prior to “partnering.” To prove that these differences in testosterone levels are naturally occurring and biologically determined, we’d need to show cross-cultural universality in men’s pre-parental and post-parental testosterone levels. I’m not aware of any research on this topic.

__________

Note: this column was originally posted on Inequality by (Interior) Design and is reposted with the author’s permission.

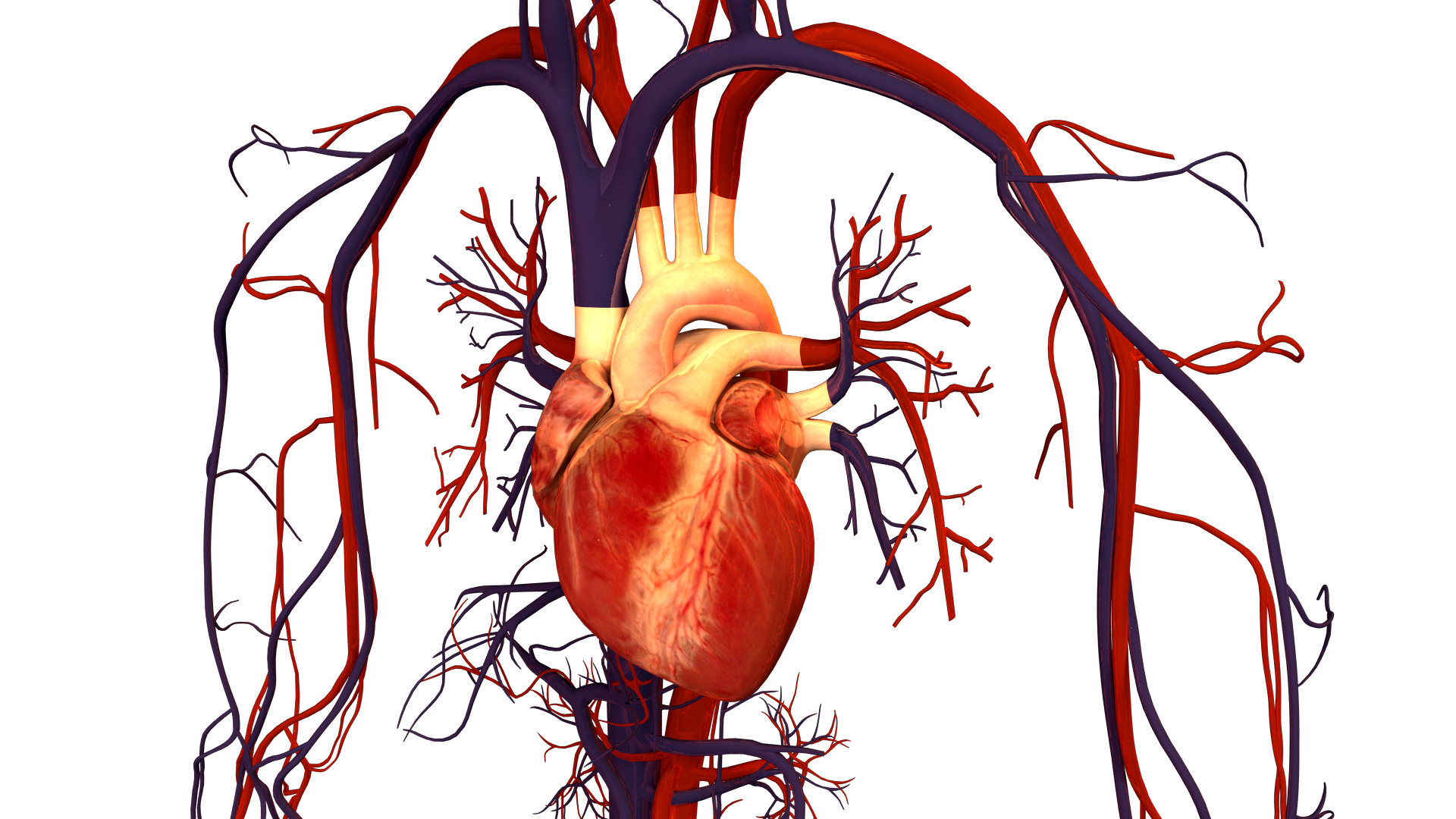

As a women’s health researcher, I am concerned about how long it is taking to bring attention and resources to this problem. After all, it has been decades since we’ve learned that cardiovascular disease affects women every bit as much–or even more–than it does men. Indeed, since 1984, cardiovascular disease has killed

As a women’s health researcher, I am concerned about how long it is taking to bring attention and resources to this problem. After all, it has been decades since we’ve learned that cardiovascular disease affects women every bit as much–or even more–than it does men. Indeed, since 1984, cardiovascular disease has killed