The new Avengers movie just came out. I haven’t seen it yet. But I’m a fan of superhero movies. It’s not something I’m particularly proud of as a feminist. But I’ve been reading comic books since I was a kid and seeing some of those characters on the big screen brings back lots of memories and childhood fantasies about superpowers. The interwebs have been alight with discussions about women superhero characters in this movie and whether those of us who care about gender equality ought to be happy about them or not. Some have argued that Black Widow and the Scarlet Witch are feminist heroes we ought to celebrate. Others have been more critical. Regardless of which side you fall on, it’s hard to deny that the cast of superhero men standing alongside Scarlett Johansson (who plays Black Widow) casts her as a bit of a Smurfette.

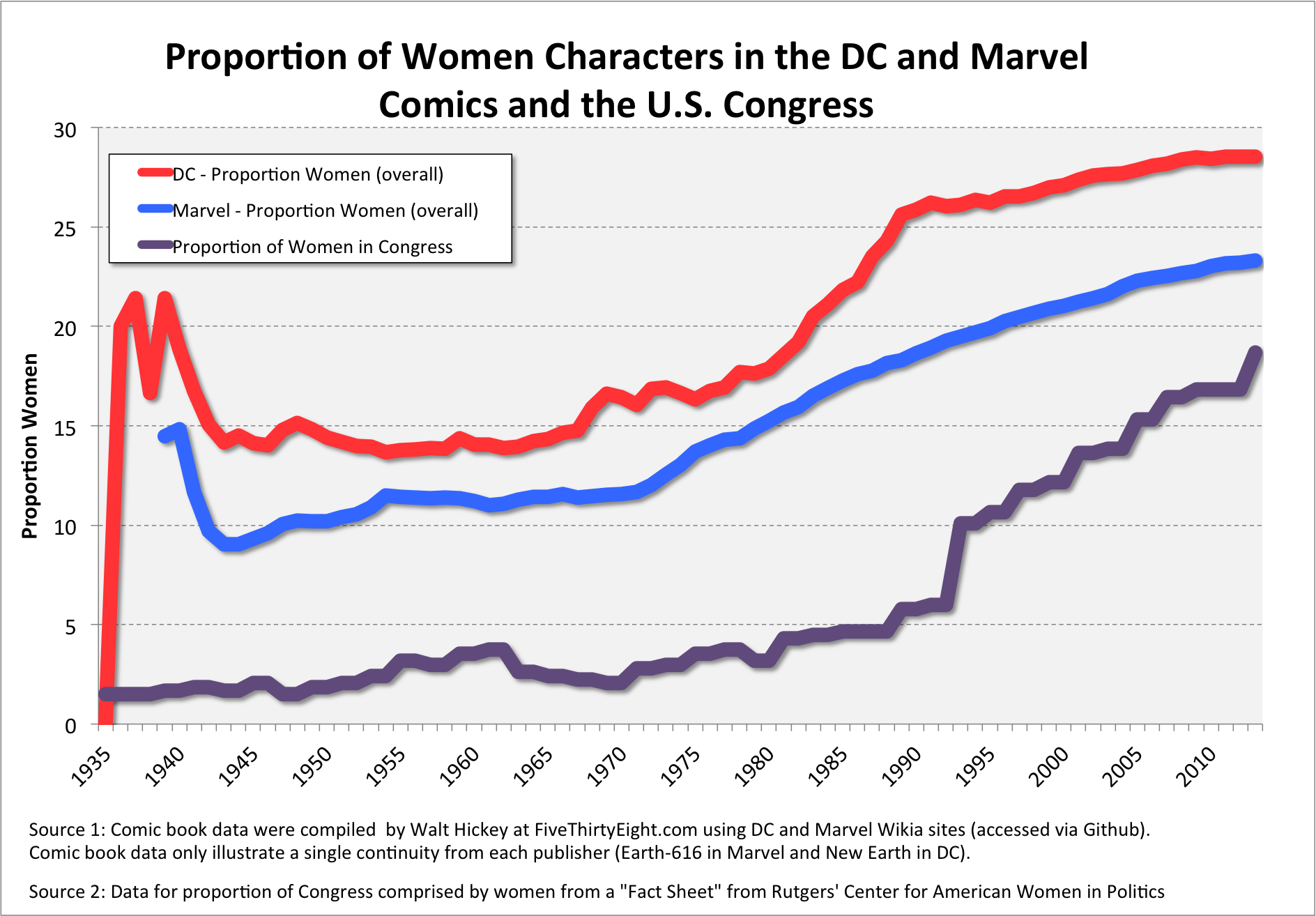

Over at FiveThirtyEight.com, Walt Hickey has written a series of posts of gender representation in comic books (here) and comic book movie portrayals of (see here and here). In his initial post, Hickey collected data from DC and Marvel Wikia databases to get a sense of all of the characters each comic book publisher had produced.* More characters have been produced than you might imagine. DC has created just shy of 7,000 characters. The Marvel database includes more than 16,000. Using this data, Hickey made some basic claims about the entire comic book universes each publisher has produced. One fact we learned from this is that the ratio of women characters to men has been slowly improving. For instance, in 2013, the Marvel universe was about 23.3% women, while the DC universe was approximately 28.5% women. But, the graphs show that the ratios appear to be leveling out shy of 30%. Men are more likely to be deceased than women. Women characters in both universes are most likely “good” (as opposed to “neutral” or “bad”) characters, while there are more “bad” men than “good” ones in both comic book universes. While there are some signs of change in this data, it doesn’t come close to achieving gender parity.

Using Hickey’s data, I’ve graphed the proportions of women in each comic book universe along with the proportion of women in Congress over the same period of time (below). One fact immediately apparent is that superhero women seem to be faring a bit better than women in U.S. politics. In fact, the proportions of women in many of the “heroic” professions in the U.S. fall well below Marvel and DC’s universes. Women in the U.S. comprise less than 25% of federal law enforcement, less than 15% of local police and sheriff’s officers, and less than 10% of state police and highway patrol (here). Women comprise less than 4% of career firefighters in the U.S. (here). Similarly, women are less than 20% of the U.S. military as well (here). Virtually all of the jobs in the licit economy that involve higher than average work-related death rates are—perhaps unsurprisingly—dominated by men (here). Certainly, which occupations are deemed “heroic” in the first place is also important to consider. Indeed, the idea of a “hero” seems already gendered.

Superheroes are important for lots of reasons. The stories we celebrate tell us important information about the societies in which we live. The characters we celebrate and those we oppose provide us with information about what we value. As Arthur Berger writes, “There is a fairly close relationship, generally, between a society and its heroes” (here), to which Jon Hogan adds: “The superhero comic book is part of popular culture because it can help us better understand what traits we value and why we value them” (here). Berger and Hogan seem to be asking us to consider what comic books are doing, rather than what they should be doing.

Superheroes are important for lots of reasons. The stories we celebrate tell us important information about the societies in which we live. The characters we celebrate and those we oppose provide us with information about what we value. As Arthur Berger writes, “There is a fairly close relationship, generally, between a society and its heroes” (here), to which Jon Hogan adds: “The superhero comic book is part of popular culture because it can help us better understand what traits we value and why we value them” (here). Berger and Hogan seem to be asking us to consider what comic books are doing, rather than what they should be doing.

I used to assign a short reading by Ursula K. Le Guin to students at the conclusion of a gender studies course I taught. Le Guin is a science fiction writer (a genre dominated by men). She’s perhaps best known for The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)—a story about an alien society without gender. The alien race in the story shares the biological and emotional characteristics of both sexes, only adopting sexed characteristics (both embodied and emotional) once a month. After writing the novel, Le Guin was often asked whether she believed we were headed for a post-gender society. She responded in the Introduction to subsequent editions:

Yes, the people in it are androgynous, but that doesn’t mean that I’m predicting that in a millennium or so we will all be androgynous, or announcing that I think we damned well ought to be androgynous. I’m merely observing, in the peculiar, devious, and thought-experimental manner proper to science fiction, that if you look at us at certain odd times of day in certain weathers, we already are. I am not predicting, or prescribing. I am describing. I am describing certain aspects of psychological reality in the novelist’s way, which is by inventing elaborate circumstantial lies.

Perhaps when we celebrate comic book universes, we are not imagining future societies and futuristic possibilities. Perhaps they are best thought of as stories about who we are today and what our society actually looks like. Le Guin argues that science fiction is better understood as descriptive than predictive. Perhaps, in other words, comic books are “elaborate circumstantial lies” about who we actually are.

Perhaps when we celebrate comic book universes, we are not imagining future societies and futuristic possibilities. Perhaps they are best thought of as stories about who we are today and what our society actually looks like. Le Guin argues that science fiction is better understood as descriptive than predictive. Perhaps, in other words, comic books are “elaborate circumstantial lies” about who we actually are.

Beyond the numbers, however, there are also other features of gender that are difficult to ignore. Men and women superheroes are also depicted in patterned ways that reinforce problematic assumptions about gender. Artist Kevin Bolk re-imagined the poster for the original Avengers movie depicting Black Widow in a “masculine” pose and Hawkeye, Captain America, Thor, Iron Man, and Hulk in stereotypical “feminine” poses. The image attests to the fact that the number of women is really only the tip of the iceberg when in comes to addressing gender inequality in comic books.

Comic book universes (particularly those that have become famous outside comic cons and fan circles) exaggerate and celebrate gender differences. There are writers and artists who push back against this tendency in the industry. And important strides have been made. Women writers and artists are receiving more recognition and support. Both DC and Marvel have introduced gender and sexual minority characters. But, which of these characters will achieve fame and fortune is more of a question. I don’t know of existing data on the comic book characters about which movies have been made, but my hunch is that that sample would include a higher proportion of men and fewer non-white characters than each universe boasts.

________________________

*The data are publicly available at Github if you’re interested in playing around with it. The data are only collected through 2013 and only for a single continuity for each publisher – Earth-616 (Marvel) and New Earth (DC).

Comments 3

Daily Feminist Cheat Sheet — May 7, 2015

[…] does the proportion of women in each comic book universe compare to the proportion of women in Congress over […]

Studying Race and Gender in Comic Books with Color Codes | Inequality by (Interior) Design — June 4, 2015

[…] representative is beyond the scope of the post. But, it’s an interesting question. While we know that there are dramatically fewer women in comic books than men, inequality is not only a matter of numbers. Portrayal matters a great deal as well, and color […]

Rosalyn — March 5, 2016

excellent post Im a massive Marvel fan from Sweden