A few years ago, before I had even begun to contemplate having a child, I regularly read Ayelet Waldman’s blog, Bad Mother, now repurposed in book form. What most appealed was the sense that someone was pulling back the curtain on what was always made to seem (with a ring of beatific sacrifice) easy, naturalized, and rewarding. Waldman’s commitment to honesty about the work, boredom, and at times ugliness (in all senses) of mothering her four children felt transgressive and, with its escape-valve honesty, like a relief. Soon enough, it seemed like the label “bad mother” began to proliferate — as angsty confessionals began to turn up everywhere. What has remained fixed, however, is the polarized use of the terms “good” and “bad” although their definitions almost interchange as Elissa Strauss astutely writes: “In the beginning, bad mommy was gritty and sometimes off-putting, but overall she offered a more realistic parenting model than the good mommy, and so she took off on mommy blogs and in the hearts of conflicted mothers across the nation.”

Soon enough, it seemed like the label “bad mother” began to proliferate — as angsty confessionals began to turn up everywhere. What has remained fixed, however, is the polarized use of the terms “good” and “bad” although their definitions almost interchange as Elissa Strauss astutely writes: “In the beginning, bad mommy was gritty and sometimes off-putting, but overall she offered a more realistic parenting model than the good mommy, and so she took off on mommy blogs and in the hearts of conflicted mothers across the nation.”

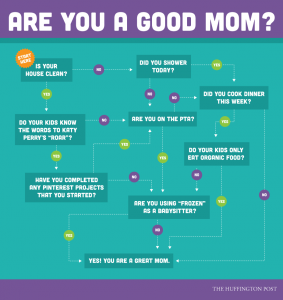

As Strauss recapitulates, then “bad mothers” started getting “a little judgey themselves” as terms such as “mom-policing” and “sanctimommy” proliferated in a culture of “reverse bullying,” as she puts it, that still bifurcates how mothering is classified, often enough with political implications. The recent brouhaha that emerged when New York City first lady Chirlane McCray dared to admit her ambivalence about about giving up work was quickly translated into a meant-to-be-shocking “I Was a Bad Mom” headline. Jennifer Senior’s astute retort blames the media-generated need to distort ambivalence into mom-shaming. A video produced for American Greetings’ online greeting-card shop went viral this spring, playing upon the impossible-hardship-of-motherhood theme, with its problematic categorization, once more, of motherhood as a job which is endlessly demanding but eternally worthy.  Between the tropes of “good mother” and “bad mother” rests the realities of most women.

Between the tropes of “good mother” and “bad mother” rests the realities of most women.

Thankfully, a body of literature has sprung up by writers committed to investigating the nuances of an experience that is perpetually shifting, even moment to moment. Speaking out honestly about mothering can still be fraught, but as feminist blogger Andie Fox writes: “By sharing private and difficult moments as mothers we create a more complete picture of the reality of motherhood — it ultimately frees us all…. But the fear in us in disclosing is palpable — that we might be frauds and that our secret moments exclude us from being good mothers.”

The wealth of essays found within The Good Mother Myth, edited by Avital Norman Nathman is a treasure. With chapters by Girl w/Pen’s own Deborah Siegel and Heather Hewett the thread that weaves throughout is exploration of what “good” and “bad” even means when it comes to parenting. If being “bad” means eschewing cultural constrictions, these writers are glad to take on that mantle, often while still feeling the need to explain how this deviation is for the best. The tropes often found within literature about parenting are all here: “I’m too young,” “I’m not ready,” “But my partner’s left the picture,” “I’m not sure about the sacrifice,” and “I haven’t overcome my own childhood enough,” alongside heavier issues such as mental illness, postpartum depression, and anxiety.

More unusual are contributions from parents positioned outside the mainstream of what is often represented. Erika Lust, an independent filmmaker who currently lives in Spain, writes straightforwardly about prioritizing time without children for the sake of her career and for her partnership as she hopes that motherhood, rather than challenging sexuality, can be a source of its inspiration. In the essay, “Confessions of a Born-Bad Mother,” author Joy Ladin writes astutely about transitioning from male to female: “I might be recognized by mothers (the ultimate judges) as a ‘great dad,’ but the top of the fatherhood scale fell well short of the lowest rung of true motherhood.” Ladin’s perspective, after inhabiting both gender roles, is intriguing as the “namelessness” she experiences as a transgender parent opens up a new space for negotiation, albeit, as she writes, one often filled with tears and confusion.

Food is a common theme. In “The Macaroni and Cheese Dilemma” Liz Henry comments on her guilt in reaching for the ubiquitous boxed product in the context of writing about parenting and poverty alongside decisions around abortion. “It may not be a roasted chicken with asparagus and couscous, but that doesn’t mean it’s not Good Mothering,” says Carla Naumburg in “Mama Don’t Cook.” Naumburg takes on the onus of “nourishing souls” at the family kitchen table, with “good family meals,” an obligation she refuses. In Heather Hewett’s touching essay, “Parenting Without a Rope,” she navigates caution and overprotection in regards to her daughter’s life-threatening allergies, and the delicate positioning the child-with-allergies and the parent-of-a-child-with-allergies must take within the classroom and social situations. Competition, self-perception, and the spiraling thoughts that ensue, are hilariously captured by Amber Dusick as she writes about a trip to Target in which she spots another Mom who looks perfectly put together and whose kids look “calm and clean and happy.” After which, she writes, “my heart sank — pretty much all the way down to my vagina, and then easily fell out on to the seat of the car.” The new pressures of selective exhibitionism, mediated through social media, is Sarah Emily Tuttle-Singer‘s theme in “No More Fakebook.”

What’s clear is that mothers are caught between more than just the polarizations of “good” and “bad.” There’s joy and hardship, fury and sweetness, days of spiraling despair and moments of unbridled amazement. Judgment lurks behind every corner, and some days it’s the self in the mirror who seems to be casting the sharpest glance. As the phrase “good mother” is turned over and over, its meaning becomes more porous and latticed by nuance. Kristin Oganowski writes, “I challenged the idea that the ‘good’ pregnant woman keeps quiet when she loses a pregnancy, and that the Good Mother hides the loss from her other children and carries on with work and family obligations as if nothing happened.” In “The Impossibility of the Good Black Mother” T.F. Charlton takes on issues of race when she writes, “Still, the images projected on me as I walk my neighborhood streets are not of the Good Mother. No, they are of the Black welfare queen, the baby mama, of women maligned and demonized as everything a mother should not be, foil and shadow to the Good (White) Mother.”

Blogger Andie Fox, while on an annual holiday with female friends and their kids, sans husbands, is frank about the joy they feel when unleashed from the imposition of societal expectation. Hearkening back to a line by foremother Adrienne Rich, Fox writes, “Her discovery back in the seventies that being a ‘bad mother’ could actually make you a ‘happy mother,’ and that happy mothers are good for their children, should not have been news to me when I started my own journey into motherhood in 2005.” Commenting that Rich’s thoughts are “as revolutionary today as they were then, more than forty years ago,” so the cycle spins.

As a poet, I have to give a shoutout to two other books that have joined The Good Mother Myth on my night table’s stack. Rachel Zucker, whose work I have reviewed previously, teaches literature and creative writing and also works as a doula. Motherhood has always been central within her work, but never as explicitly. In Mothers, Zucker writes primarily about her relationship with her own, Diane Wolkstein, a professional storyteller. Zucker’s prose rotates around an axis of trying to understand their relationship, foremost as a daughter, but also as a mother of three sons, as a writer in search of literary foremothers, and as an adult woman who still craves mothering from other maternal figures.

I appreciate Zucker’s celebration of the literary mothers she has had, particularly Alice Notley, whom she quotes and corresponds with throughout the writing of this book. Yet, much reads like a series of journal entries about coming to terms — literally — about what motherhood means as Zucker gathers fragments from her past and holds them up against her present moment. I can’t help but wish she offered more synthesis of what she’s connecting, or, at the least, more nuance and less worry. Instead, the lines feel collaged onto the page with the reader left to associatively connect the gaps. While her diary-like entries intrigue, there seems a deliberate turn from the satisfaction of a narrative arc. I suspect this is, conscious or not, part of Zucker’s refusal to participate in her mother’s art, storytelling, and to break her writing in parallel to her subject(s) — how mothering shatters continuous time and divides the mind.

The book’s epilogue is its most surprising part — and the most powerful. The inclusion of a letter Zucker’s mother writes to her, eschewing this very book’s publication and urging Zucker not to tell these stories — takes on a poignant resonance by the time the reader gets to it. Clearly, her own urge to write is both heritage and embattlement. She ends with the central tone of ambiguity mothering represents for Zucker: “There are mothers. I found and lost them and was born to one and she is hardly mine. What I make of her. Neither real nor wrong nor ever really mine.”

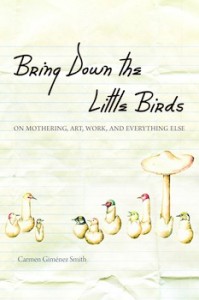

After meeting Carmen Gimenez Smith at the 2014 AWP conference, and then hearing her speak at this truly innovative colloquium on feminist poetics, I was eager to read her contribution, published at the vanguard of these other two. Like Zucker, Gimenez Smith has to untangle her mother’s story in order to understand her own. In Bring Down the Little Birds: On Mothering, Art, Work, and Everything Else she catalogues parts of her life as a mother of a toddler, as a professor, as a poet, as a spouse, as a daughter, as someone who is preparing to have a second child. Written in single lines or short bursts of prose, her writing is lyrical, thoughtful, and shot through with honest anger and frustration as well as the amazement that comes in sudden, saving bursts. The narrative of more fully inhabiting motherhood, as she goes from having one child to two, is freighted with the simultaneous worry about the demise of her mother’s memory and the complicated recognition of Gimenez Smith’s need, as a mother, to be mothered, while recognizing she may well soon be in the role of parent to her own mom.

After meeting Carmen Gimenez Smith at the 2014 AWP conference, and then hearing her speak at this truly innovative colloquium on feminist poetics, I was eager to read her contribution, published at the vanguard of these other two. Like Zucker, Gimenez Smith has to untangle her mother’s story in order to understand her own. In Bring Down the Little Birds: On Mothering, Art, Work, and Everything Else she catalogues parts of her life as a mother of a toddler, as a professor, as a poet, as a spouse, as a daughter, as someone who is preparing to have a second child. Written in single lines or short bursts of prose, her writing is lyrical, thoughtful, and shot through with honest anger and frustration as well as the amazement that comes in sudden, saving bursts. The narrative of more fully inhabiting motherhood, as she goes from having one child to two, is freighted with the simultaneous worry about the demise of her mother’s memory and the complicated recognition of Gimenez Smith’s need, as a mother, to be mothered, while recognizing she may well soon be in the role of parent to her own mom.

Bring Down the Little Birds bristles with honest emotion as Gimenez Smith explores the conundrums mothering presents. She writes about the presence of her belly “like a bullet” in the room when she discusses intellectual matters at a student’s defense and the hiring of a housecleaner “to serve as a mediator between the house and me.” Her writing manages to be sharp even as she hones in on the liminal: how hard enduring a moment can be, how much anger is buried inside a dose of joy, the amazement glittering inside still dangerously sharp fragments.

“I want so much” she says frankly, and then later, “A long day at home, no work. Full of resentment.” All of which is tempered with lovely recognitions of other ways in which time can now pass, as she says of her firstborn child, “I’m telling him the world and he is telling it back.” Married to another writer, both know they must guard their time, yet, “My personal time comes at a larger price” Gimenez Smith writes, “I want to find a number value for it, but I don’t have the time. It seems like two and a half to my husband’s one.”

Hovering between poetry and prose, a strength is Giminez Smith’s ability to telescope forwards and backwards, as she remembers her life, pre-child, and looks into the future. Her meditations into her maternal legacy are rich, and allow Gimenez Smith to frame her own entry into motherhood: “I grow into my mother, I grow old with her.” She is skilled at writing about the underweave, the backing that holds a garment together, and there we find this book’s lyrical gift, keen observations weighted down by reality, flying into unseen spaces.

“The good enough mother. The real mother. Other mothers,” Zucker meditates in the middle of her book. These shifting variations are pertinent to all these writers. Zucker simply continues: “I too seem to have gotten older. Am the mother.”

Comments