The other week, Girl w/Pen bloggers and masculinity studies scholars Tristan Bridges and CJ Pascoe called us to pause the war on pink and take a look at boys’ toys, prompting a response from media studies scholar Rebecca Hains (author of the forthcoming The Princess Problem: Guiding Our Girls Through the Princess-Obsessed Years) and a reflection from me on feminist history and popular feminist debate.

The other week, Girl w/Pen bloggers and masculinity studies scholars Tristan Bridges and CJ Pascoe called us to pause the war on pink and take a look at boys’ toys, prompting a response from media studies scholar Rebecca Hains (author of the forthcoming The Princess Problem: Guiding Our Girls Through the Princess-Obsessed Years) and a reflection from me on feminist history and popular feminist debate.

This week, I invited Rebecca to dialogue with me. Here is our exchange. And keep an eye out for some thoughts on it all coming soon from Girl w/Pen blogger Susan Bailey, too! You can learn more about Rebecca’s work here.

Deborah: In my post the other week (“Who’s Afraid of the War on Pink?”) I looked back at the history of arguing “enough about girls, let’s focus on boys,” to mixed effect. You make the thoughtful point that the ploy is not merely a harmless rhetorical effect. Can you elaborate?

Rebecca: In all honesty, the argument that we need to stop (“or at least pause”) the war on pink didn’t even come off as a rhetorical device to me. I’m sad to say that it just came across as ill-informed. There isn’t a war on pink; there’s a thoughtful, measured argument that while pink isn’t inherently bad, it’s limiting the play worlds and imaginations of boys and girls alike. So “Who’s Afraid of the War on Pink” reads, to me and my colleagues, like a straw man argument. The authors were conjuring up a nonexistent epidemic of myopic thinking, instead of engaging with anyone’s actual writing on the subject of girl culture and the rise of pink. I expect better from our esteemed colleagues in masculinity studies: if they would like to engage with those of us working in girlhood studies, and perhaps learn from our successes (we’re happy to share what we’ve learned), that would be terrific–they just need to demonstrate that they’ve read at least some of our work so that we can have a meaningful conversation.

Besides, straw-man arguments strike me as more problematic coming from a feminist academic blog like Girl w/Pen than, say, an anti-feminist source like Christina Hoff Sommers. (A case of “the medium is the message,” perhaps?)

Deborah: Tell us a bit about your book that’s coming out next fall, The Princess Problem: Guiding Our Girls Through the Princess-Obsessed Years (Source Books, 2014). Is there any way in which you think girls can be active agents in princess play? In what ways do you hope your book will steer popular debate? And what do you most want to change?

Rebecca: Thanks for asking. The Princess Problem is really a handbook for parents to raise media-literate daughters–girls who are able to think critically about marketing, the beauty ideal, gender stereotypes, and race representation. This is an important task for 21st-century parents: We must coach our children, guiding them to become critical viewers of media culture in general. And yet media literacy is not something that’s a mainstream concept yet in the U.S.; many other countries include media literacy in their K-12 curricula, but that’s not the case here. I’d like that to change.

I focus in my book on princess culture in particular because “princess” is so pervasive–it’s THE defining pop culture phenomenon in early girlhood. And it’s the perfect example to use in a text on raising media literate girls because the issues we need to discuss with our daughters so often differ from than the issues we would discuss with our sons. (For example, body image issues are a very different beast when it comes to girls and boys.) But the principles I teach in The Princess Problem could easily be extrapolated to raising media-literate sons, too.

And yes, I absolutely believe girls can be active agents in princess play. Kids are not passive victims of media and toys; they’re active consumers who regularly defy our assumptions. That’s a position I’ve espoused in some of my earlier work–for example, my study of girls and Bratz dolls.

It’s important to note, then, that in The Princess Problem, my goal is not to persuade girls that princesses are bad or to “de-princess” them; rather, it is to help parents help their girls reason become critical viewers who can see that there are many, many ways to be a girl.

Deborah: I loved your recent post at Sociological Images (“When Cowboys Wore Pink”), where you concluded, “Monochromatic girlhood drives a wedge between boys and girls — separating their spheres during a time when cross-sex play is healthy and desirable, and when their imaginations should run free.” Some of our Brave Girls Alliance colleagues have created incredible alternatives. From where you stand, what do you see as some of the most exciting challenges to the children’s industrial complex as we know it?

Rebecca: The Let Toys Be Toys movement is doing terrific work challenging the status quo in the UK. By calling for toys to be desegregated–grouped by theme or interest type, rather than by gender—they’re empowering parents and children to think outside of the pink and blue boxes that marketers have been placing children into. I’d really love to see a comparable movement here in the U.S. and Canada. With folks like Melissa Wardy of Pigtail Pals, Michele Yulo of Princess Free Zone, and Ines Almeida of Toward the Stars raising so much consciousness about the limitations that today’s marketing foists upon kids of both sexes, it’s the right time.

I’d like to see a movement that goes one step further, too, and challenges marketers to put an end to the incessant pink-washing. By “pink-washing,” I’m specifically referring to the instances where marketers or toy makers create a product that is pink for no reason other than to make it as girly as possible. After all, there’s nothing wrong with pink–it’s a perfectly nice color–but there IS something wrong when it’s a) promoting sex role stereotypes and b) basically the only color found in little girls’ worlds. They deserve a full rainbow of colors.

Pink-washing is unfair to our boys, as well: I just heard from a mom the other day whose two-year-old son wanted a toy shopping cart for his third birthday. All she could find at her local Toys R Us was a pink cart. She bought it anyway–but she knows that the adult men in her family are likely to think it’s weird (which is a shame). But, come on; have you ever seen a real shopping cart in pink? I haven’t. I doubt they exist. Pink-washing toys that have no good reason to be pink–that would be considered gender-neutral if they were not–perpetuates so many retrograde stereotypes about sex roles, it’s offensive.

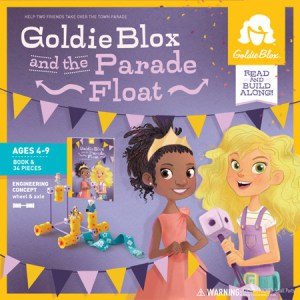

Deborah: When GoldieBlox, a company initially celebrated for its creation of a toy designed to foster girls’ interest in engineering, ultimately disappointed many of us by slapping a princess narrative on it, it seemed challenging, at the time, to articulate a position that both acknowledged the step in the right direction and pushed for more. (My feeble attempt posted here.) In the war between industry and better alternatives, is it always necessary, do you think, to choose sides? How do we measure progress in a world half-transformed?

Rebecca: I prefer to think of it as a dialogue rather than a war. I don’t want to fight companies; I want to hold them accountable and ask them to do better. Companies have so many stakeholders to work with that they often don’t realize that they are perpetuating gender biases. If they receive constructive criticism from enough parents and advocates, though, they can create better offerings.

Unfortunately, the world is indeed half-transformed in these matters, and it’s often a case of one step forward, two steps back. For example, we can look at Disney’s films and see that slowly but surely, their representations of race and gender have been improving with time. I believe that their efforts at racial inclusivity and empowered female characters signal that they’ve been paying attention to their critics over the years. The problem is that in a behemoth company like Disney, change comes very slowly; and their own Consumer Products Division isn’t keeping pace with the positive changes within the Studios division.

So when it comes to the toys, we’re seeing the same old stale ideas about what’s “princessly,” or stereotypically feminine–even when the products are based on innovative new on-screen characters. That was certainly the case with Disney’s Consumer Products Division’s horrible redesign of Merida last year: she was strong on screen, per Pixar’s wishes; but as her look didn’t “fit” with the existing high-glamour Disney Princess brand, Disney’s Consumer Products Division made several changes to Merida’s looks (see posts here, here and here), undercutting everything parents and kids loved about Merida. What a conundrum.

So when it comes to the toys, we’re seeing the same old stale ideas about what’s “princessly,” or stereotypically feminine–even when the products are based on innovative new on-screen characters. That was certainly the case with Disney’s Consumer Products Division’s horrible redesign of Merida last year: she was strong on screen, per Pixar’s wishes; but as her look didn’t “fit” with the existing high-glamour Disney Princess brand, Disney’s Consumer Products Division made several changes to Merida’s looks (see posts here, here and here), undercutting everything parents and kids loved about Merida. What a conundrum.

Deborah: It’s a conundrum indeed. Frozen, anyone? I’m already wondering how princessly those Anna and Elsa action figures will be.

I invite you to follow me on Twitter @deborahgirlwpen, join me on Facebook, and subscribe to my quarterly newsletter to keep posted on my coaching workshops and offerings, writings, and talks.

Comments 4

Getting your daughter through the princess stage | blue milk — January 16, 2014

[…] From Girl w/ Pen! with Deborah Siegel interviewing Rebecca Hains in “Girls, Boys, Feminism, Toys”. […]

Back to Pink, Kind of. | yourbabynanny — January 16, 2014

[…] is kind of a reblog from Bluemilk, I saw her post referencing the recent article/discussion Girls, Boys, Feminism, Toys: Deborah Siegel and Rebecca Hains Discuss. The discussion between Deborah Siegal and Rebecca Hains, points to issues with the anti-pink […]

Elline Lipkin — January 23, 2014

Thank you Deborah and Rebecca for such a thoughtful discussion. This was great to read and I have a lot of faith the the conversation is changing across venues, academic and otherwise. It's especially useful to think again about how these stereotypes affect boys and how to moderate our expectations in a "half-transformed world." There's so much change to wish for and hopefully make happen, how to take the most deliberate next step often seems the challenge.

Deborah Siegel — January 26, 2014

Thank YOU, Elline, for continuing to lead the conversation on this all at GWP with us. And for the amazing work you do (and of course your awesome book Girls Studies). Here's to the deliberate next step -- steps -- and to continuing the work, all around.