I studied a group of fathers’ rights activists and men undergoing divorce, separation, and custody battles for a little over a year. Fathers’ rights organizations were, for me, an interesting place to study anti-feminist gender politics because they are, in many ways, one of the most successful arms of the men’s rights movement more generally. Fathers’ rights activists and advocates are asking for things feminists have long sought from men: a greater investment in their children, a move toward a model of parenting that moves beyond the “provider” model. And all of these things make fathers’ rights groups the most politically palatable and mainstream of the virulent misogyny that characterizes the men’s rights movement more generally.

At the weekly meetings I attended, I regularly heard men pushing back against this stereotype, wanting to be “more than a paycheck” in their kids’ lives. And in my experience, the men who gave up on their custody battles the most quickly, those who lost contact with their children, or failed to show up at the times designated by the court had one thing in common: most of them had daughters. In the group I studied, men with sons stuck with and struggled through really challenging custody arrangements and incredibly tense relationships with the mothers of their children. My study did not involve a sample from which I can generalize about this idea. But there is a host of interesting scholarship on how fathers in straight couples engage with their children contingent upon the gender of their children.

Gender is a big topic of discussion when people have babies. It shapes the sorts of names we consider (or don’t). It shapes the way we set up the nursery, what color we paint the walls, the infant clothes we buy and receive, the things we imagine our child doing one day (or not). And research suggests that, among heterosexual couples, fathers are more invested in gender conformity than mothers. It’s not uncommon to hear that heterosexual men want boys—or are expected to want boys. Sex selective abortion is a really powerful illustration of son preference. But son preference can be measured in other ways as well.

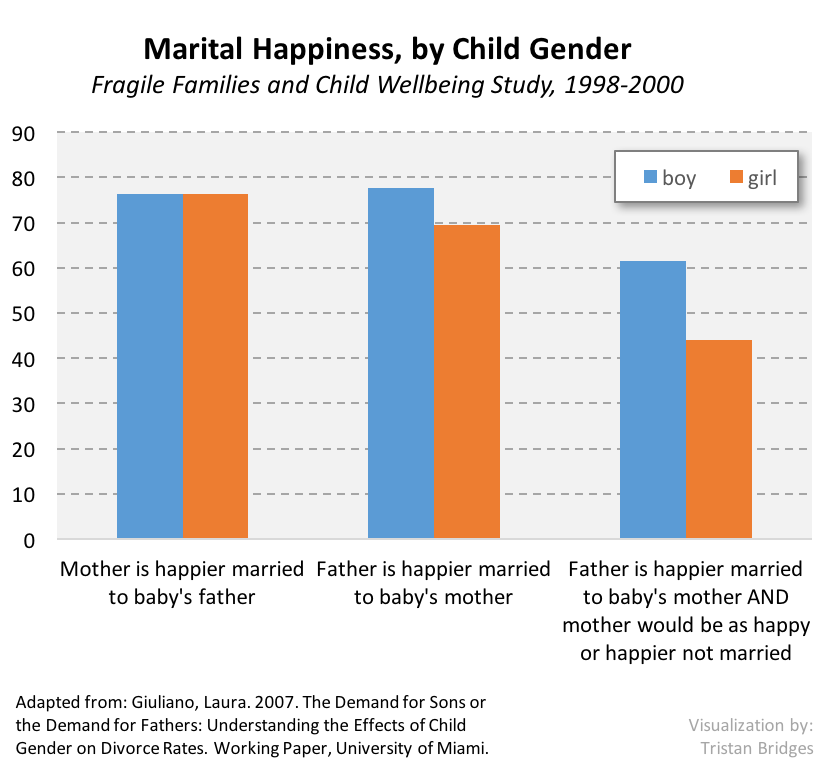

I just read a working paper by economist, Laura Giuliano examining the effects of having sons versus daughters on heterosexual marriages.* The paper was initially published as a working paper in 2007. So, it’s a little dated. But the data and argument are really fascinating, if frustrating. Children take a toll on marital happiness for both mothers and fathers (shocking, I know). Among heterosexual married mothers in Giuliano’s sample, there was no meaningful difference in the level of marital happiness among mothers who had sons compared to those who had daughters. Among fathers, however, the story is a bit more complex. Heterosexual married fathers with sons had significantly higher levels of marital happiness than those with daughters (see graph below).

This makes men look like the problem here. But, Giuliano found that women are invested in this issue as well. She also discovered, for instance, that couples in which the fathers had higher levels of marital happiness but the mothers said that they would be as happy or happier NOT married were disproportionately likely to be couples with sons. This suggests that mothers in heterosexual marriages that make them unhappy are much more likely to remain married if the child happens to be a boy. One hypothesis for which Giuliano found support is that this discrepancy is produced by a collective perception that sons and daughters have different needs and that fathers are more essential in the raising of boys than girls. Add to this that fathers of sons in Giuliano’s sample also engaged in different parenting practices. Fathers with sons were more likely to look after and spend more time with their kids and the wives of fathers with sons held more positive views of them as parents.

There’s a lot of literature out there on how we need to get men engaged in modeling healthy masculinity to the next generation—showing boys that parenting and care work aren’t feminine practices; they’re human practices. But all of this can’t be accomplished alongside an “androcentric” ideology that holds that boys and men are somehow more important than girls and women, more deserving of our time, attention, and apparently even affection sometimes. It’s great that men are participating more as parents. But we have a long way to go if they’re still waiting to see if the child is going to be “Matthew” or “Megan” before deciding whether to ask for a more flexible schedule at work.

_______________________________

*I learned about this research from Emily Bobrow’s great essay in The Economist, “It’s a Boy Thing” (shared on social media by Philip Cohen).

Comments 1

Masculinity and Son Preference Among Heterosexual Men | Chicago Black Pride — May 27, 2016

[…] This post originally appeared at Feminist Reflections. […]