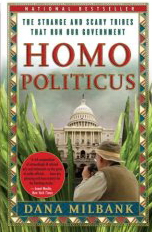

The year 2008 has given us a strangely-titled book, Homo Politicus – The Strange and Scary Tribes that Run our Government by Dana Milbank, columnist for the Washington Post. Using the language of cultural anthropology and the terminology of ethnography, he tells one tragic comedy after another about how Washington rules the “American Empire.”

Milbank races through tale after tale exposing the folly of unrestrained egos. The New York Times’ book review described it this way:

….a rich compendium of astoundingly ill-advised acts and statements on the parts of public officials, he fails to register the threat posed by such ineptitude. Instead he treats greed, egomania, ruthlessness, corruption, stupidity and extreme feats of partisanship lightly…. It’s as if he thinks these things are funny. (Janet Maslin, New York Times, December 20, 2007)

Milbank as pseudo-ethnographer calls his tribe “Potomac Man,” drawing and elaborating upon each of his analytical categories: status, caste, kinship, folklore, folk law, norms, deviancy, shamanism, aggression, taboo, festivals, rituals, human sacrifice, and fertility rites. After introducing each concept he tells a handful of stories to illustrate the primitive character of the Washington, DC culture.

Real ethnographers should study the way Milbank ends most stories with a witticism or hilarious comment. A little bit of humor goes a long way, especially in long, dry qualitative accounts.

Without humor this would be an exceptionally depressing book. The author demonstrates that the government running the world’s only superpower is a byzantine ruling caste made up of wealthy White House officials, members of Congress, corporate lobbyists, and media elites. His stories reveal how this power elite has been able to do such things as convert propaganda into news, control our language (e.g., hunger becomes “low food security”), fire auditors because they do a thorough job, redefine torture, and allow a Neocon cult to make foreign policy. Ironically this autocracy claims to be the epitome of democracy.

It would be comforting if all of this were merely the doings of the present administration. These tribal maneuvers, according to Millbank’s stories, are typical of both Republicans and Democrats and characteristic of earlier administrations. However Millbank’s piles and piles of contemporary anecdotes left me with the impression that not until the Bush administration did American government become a joke.

Let us hope that enough people will take Milbank’s critique of American government seriously to fix the broken system. Obviously not enough safeguards have been built into the political system to ensure that it remains a government of and by the people. That is not at all funny.

Comments 1

ronanderson — September 6, 2008

The author, Dana Milbank, should not be confused with political liberals. He recently wrote a very critical, unfair critique of Obama in the Washington Post.