Slowly but steadily, we’ve been introducing a number of changes around The Society Pages, particularly in the last couple of weeks. Today, as you head into the weekend, I’d like to bring your attention to the first installments of several new features that we’ll be building on, and, of course, warn you that our web editor, Jon Smajda, will be carefully carving out a new place for each of these items on our front page. Which is to say: spoiler alert! TSP 2.0 (or, more likely, 5.1.4) is on its way.

Slowly but steadily, we’ve been introducing a number of changes around The Society Pages, particularly in the last couple of weeks. Today, as you head into the weekend, I’d like to bring your attention to the first installments of several new features that we’ll be building on, and, of course, warn you that our web editor, Jon Smajda, will be carefully carving out a new place for each of these items on our front page. Which is to say: spoiler alert! TSP 2.0 (or, more likely, 5.1.4) is on its way.

Roundtables: This afternoon, our associate editor, Letta Page, put up the inaugural Roundtable, in which our intellectually curious and always gregarious graduate team members reach out to social scientists on the topics of the day. Our first features some movers and shakers talking about research on social movements, from how you do it (and do it well) to how you carve out your own role within the movement as an embedded social scientist. As Letta puts it, “This is the first of many Roundtable installments to come—a wide-ranging attempt to look at a topic through many different lenses. Soon, we’ll be taking on politics and humor and how sociologists and political scientists each have a different idea of just what polling is and does. Enjoy!”

Special Features: I’m excited to report that, as of this afternoon, we have two Special Features up for you to devour. The first is Letta’s talk with Jessie Daniels about using documentaries in the classroom effectively—and about which ones you might want to adopt. We’ve gotten some great feedback, including a number of comments from educators and students sharing their own favorite films for class, and we hope to create a permanent repository for the latest and greatest in clips, shorts, and features for your use. In our second Special Feature, grad student Sarah Shannon talks with public sociologist Joe Soss about his new book, Disciplining the Poor, and discusses how race, welfare, and poverty policy intersect. Soss gives some clear results from his research and some straightforward ways that policies might be better created and implemented.

Our Special Features will expand to include all sorts of wonderful things—from the photographic/sociological conversation we see shaping up between our own Doug Hartmann and Minneapolis photographer Wing Young Huie to edited interviews from our Office Hours podcasts and beyond.

Reading List: Just a couple of weeks old, you’ll be seeing the Reading List grow over time. Every few days or so, we’ll be putting up a new or classic work in social science that we find particularly relevant for the public discourse, and if you click on the title “Reading List” from any single article, you’ll find the whole running list. We’ve also tagged each recommendation so that, in time, we’ll make it easy for you to pull your own topical reading list on demand.

White Papers: If we keep pushing hard, we should be launching our first new TSP White Papers late next week. More in the vein of a Contexts, New Yorker, or Economist article than anything out of an academic journal, these papers are to be written by well-informed social scientists stripped of their jargon and lit reviews. In 3,000 or so words, the White Papers will give you a smart, grounded social scientific take on a given issue, and a list of suggested readings, should you hope to follow up and dig deeper yourself.

I do want to stress that, while you will notice design changes, the core mission of The Society Pages remains the same: to bring social scientific knowledge to the broadest public audience in the most accessible, open way possible. Heck, you can even follow us on Twitter (@TheSocietyPages) for thoughts from the HQ throughout the day. You won’t have to pay to read what we write, you won’t have to worry that we’re muzzling our amazing bloggers (we couldn’t possibly have the time with the prolific likes of Sociological Images, Graphic Sociology, Cyborgology…), you won’t have to look up word after word in a desperate attempt to understand what we’re saying. We’re talking about society with society.

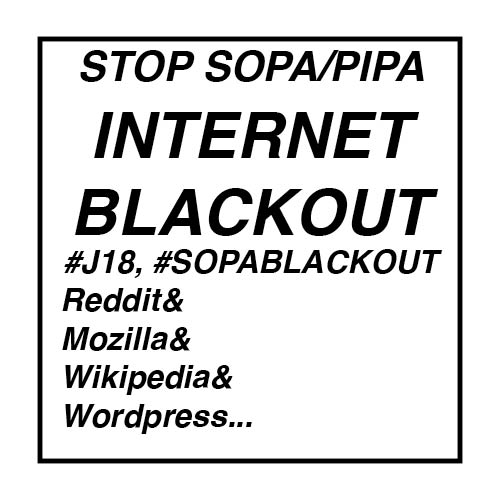

One of the core values of The Society Pages is that knowledge should be transparent, accessible, and uncensored. Proposed legislation,

One of the core values of The Society Pages is that knowledge should be transparent, accessible, and uncensored. Proposed legislation,

The Society Pages’ wondrous Monte Bute (that’s him, above, flashing the peace sign to the police) was picked by one MPR reporter as his favorite story/interview of the year, and so the reporter has published a quick update from the land-of-Bute:

The Society Pages’ wondrous Monte Bute (that’s him, above, flashing the peace sign to the police) was picked by one MPR reporter as his favorite story/interview of the year, and so the reporter has published a quick update from the land-of-Bute: