If you haven’t already, I’d encourage you to take a little time and read the new TSP white paper on religion and political culture in contemporary American life.

(https://thesocietypages.org/papers/religion-and-politics/) It is by our friend and Minnesota colleague Joe Gerteis who not only writes well and thinks big, but also has that rare ability to bring classic sociological theory and research to life and real-world relevance. We are excited how Gerteis uses Max Weber’s observations about religion in America over 100 years ago to frame an explanation for some of the cultural dynamics of our current political climate. Perhaps not surprisingly for those of you who have heard or read Joe’s previous work, ideas about social solidarity, trust, and exclusion figure prominently. And just so you know, we subjected Joe’s ideas to relentless double-blind review and our esteemed readers both agreed and offered a few observations and suggestions that made the piece even better. Suffice to say, it all fits together so seamlessly and flows so naturally you’ll may wonder why you didn’t put it all together this way yourself.

Goodmorning, dear readers! In case you haven’t noticed on our front page, a new TSP department has slipped into our site navigation bar: Changing Lenses. The first post will really tell you what we’re up to there, but the short version is that I will be teamed up with my frequent on-court foe, Wing Young Huie, to have a conversation about perspectives roughly every week. Please do check it out.

In response to the sport and politics white paper Kyle Green and I recently wrote for this site, ThickCulture writer and loyal friend of TSP Andrew Linder emailed to suggest that although Barack Obama is obviously not the first “sports president,” he may be the first “ESPN President” or “SportsCenter President.” Andrew’s point (now up on ThickCulture as a more fleshed out post—jinx!) was that, although ESPN had become a cultural fixture under Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, Obama represented the core network demographic in its first two decades of its existence and it seems to have been formative for him. To the extent that ESPN has transformed sporting culture, then, Obama is the first President to be fully fashioned in and through that new culture.

This seemed plausible enough—and was definitely borne out in a recent interview the President gave to the star sportswriter/reporter Bill Simmons. At least two things about the interview should be pointed out. The first is why Obama chose this particular venue and reporter: “Simmons,” as one report put it, “is revered by the under-30 crowd” and “has more than 1 million—1,642, 522 to be exact—Twitter followers.” Indeed, his “B.S. Report” podcast, on which the Obama interview originally appeared, is said to be one of the most downloaded podcasts on the web. The second point is how this interview and exchange reveals what a great fan of sports and sports talk our President actually is.

Not only is his obsession with ESPN’s SportsCenter evident, Obama shows himself to be an extremely knowledgeable sports fan, gifted in the arts of sports talk and debate. Talking with Simmons, the President riffs on Linsanity (claiming to have been on the bandwagon early) and the joys and challenges of coaching his daughters, argues about the best NBA teams and players of all time (MJ and the Bulls figure prominently), revisits his vision for a college football playoff, and waxes poetic about his philosophies on sportsmanship and scoring in golf. Obama even brags a bit about the “solid” crossover move he threw on NBA All-Star point guard Chris Paul in a summer scrimmage. All this is to say, Obama doesn’t just talk about sports, he’s really talking sports.

Entertaining (and impressive) as I found all of this, I was even more intrigued by a follow-up Washington Post post that explained why the President would take time out of his unbelievably busy schedule to do this interview (as well as other sports related activities such as his sit-down with Matt Lauer during the Superbowl pre-game show in February or his annual NCAA/march madness picks). “Sports,” according to the WSJ, “is a universal language that can bridge ideological, cultural, and socio-economic gaps …you are much more inclined to like people who share that fandom regardless of whether you have anything else in common with them. You feel some sort of connection to them. They speak your (sports) language.”

The piece goes on to speculate that sport may be particularly a particularly important medium (and media outlet) for Obama “whose background—biracial parents, childhood in Hawaii, Harvard Law School, etc.—is somewhat unfamiliar to many of the voters he needs to convince to back him if he wants to win a second term in November.” While talking with sportswriters “isn’t going to convince on-the-fence voters that Obama is one of them,” the writer says, we shouldn’t “forget the connective power that sports holds in the world of politics.” The article concludes: “Obama’s ability to speak the language of sports is a major political plus for him.”

Whenever I get to teach a criminology seminar, I always assign a little James Q. Wilson in the very first week. Not his influential writing on policing, mind you, but his powerful 1975 critique of academic criminology in Thinking about Crime. With his death this week, I’m Thinking about Wilson. Though we came from very different places, his work reshaped my approach and orientation as a social scientist, public criminologist, and TSP editor.

Whenever I get to teach a criminology seminar, I always assign a little James Q. Wilson in the very first week. Not his influential writing on policing, mind you, but his powerful 1975 critique of academic criminology in Thinking about Crime. With his death this week, I’m Thinking about Wilson. Though we came from very different places, his work reshaped my approach and orientation as a social scientist, public criminologist, and TSP editor.

In that book, Professor Wilson argued powerfully and convincingly that (a) we lacked strong evidence about the most critical questions about crime policy; and, (b) we then fell back on our views as private citizens when we were consulted as crime experts:

[W]hen social scientists were asked for advice by national policy-making bodies they could not respond with suggestions derived from and supported by their scholarly work … as a consequence such advice as was supplied tended to derive from their general political views as modified by their political and organizational interaction with those policy groups and their staffs (p. 49) … I am confident that few social scientists made careful distinctions, when the chips were down, between what they knew as scholars and what they believed as citizens (p. 68).

During my first heady days of graduate school, I was simultaneously encountering similar ideas from Max Weber. But the spot-on power of James Q. Wilson’s polemic hit me like a line drive to the chest. I immediately recognized myself as the sort of mushy-headed liberal who sought a Ph.D. credential as a bully pulpit for offering well-intended but baseless policy pronouncements.

After digesting Thinking about Crime, though, I resolved to conduct the sort of research that would provide a sound evidentiary base for policy. I cannot claim complete fidelity to this approach (nor, I suppose, could Professor Wilson), but it led me to research questions where I could make myself useful (e.g., employment and crime, felon disenfranchisement).

I’ve also taken to heart Professor Wilson’s admonition to distinguish the research-based opinions we present as experts from those derived from our private beliefs as citizens. My friends and students recognize this as the “hat” issue: I’ll offer a private opinion on anything from Tony Lama boots to the Fed’s quantitative easing policy, but I try to be a little more circumspect when wearing the expert hat (which happens to be a brown fedora).

While I’ll stipulate to some important “Yeah, buts” here (recognizing instances where we all stray from our high-minded ideals), Thinking about Crime still functions as both critique and call to action — for individual careers and for whole disciplines. Engaging pressing policy questions can give added meaning and purpose to our work. But such engagement is most legitimate and authoritatitive when it is founded on a real base of knowledge, interpretation, and analysis.

The good news is that “what we know as scholars” has changed much since Professor Wilson wrote in 1975. Social scientists are today assembling a more powerful, relevant, and solidly credible evidentiary base; we are thus better able to offer policy suggestions “derived from and supported by our scholarly work,” while also bringing much-needed global and historical perspectives to contemporary debates that would otherwise be framed too narrowly.

The ongoing challenge, for our careers and our disciplines, is to find new and effective ways to bring this knowledge and perspective to light. Hence, our mission at TSP: to bring social scientific knowledge and information to broader public visibility and influence. And regardless of your opinion on James Q. Wilson’s scholarship or his political inclinations, he stood as a highly visible and remarkably influential public intellectual.

photo by lokarta (creative commons license)

I’m picking up a lot of good energy and ideas — and meeting multitudes of kindred spirits — at the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) meetings this weekend. I’ve been meaning to attend these meetings for years, so I jumped at the invitation to give a paper and let my (science) geek flag fly.

I’m picking up a lot of good energy and ideas — and meeting multitudes of kindred spirits — at the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) meetings this weekend. I’ve been meaning to attend these meetings for years, so I jumped at the invitation to give a paper and let my (science) geek flag fly.

The most provocative session was a huge plenary on public engagement titled Science is Not Enough, moderated by former CNN correspondent and anchor Frank Cesno. The panelists were James Hansen (climate change scientist and author of Storms of my Grandchildren), Olivia Judson (evolutionary biologist and author of Dr. Tatiana’s Sex Advice to All Creation), and the irrepressible Hans Rosling (international health innovator, known for his amazing TED talks and, of course, a TSP podcast).

Their themes will be familiar to TSP readers: (1) science is in a “street fight” with anti-science; (2) we could and should do a better job communicating scientific evidence to broader publics; (3) science reporting is often geared less toward accurately characterizing the state of knowledge in a field and more toward conveying two extreme positions; (4) the continuing struggle to simplify, clarify, and communicate our research without dumbing it down or burying important caveats; and, (5) the tensions between value-neutral objectivity and advocacy in public communication.

The panelists came from distinctly different places on these issues and their conversation seemed to echo conversations I’ve had with Doug Hartmann at our weekly editorial meetings. Dr. Judson saw her role as stoking scientific imaginations with the curiosity to know and the passion to care. Dr. Hansen more sharply emphasized how money and power could overwhelm scientific mesages (e.g., the petrochemical industry on climate change) and our responsibility as scientists to subsequent generations. Dr. Rosling viewed his role as seizing upon and illuminating intersections of public ignorance and indisputable scientific consensus.

There were lighter moments, of course, and a good bit more scatological humor than one might expect at the AAAS meetings. Hans Rosling was incredulous when other panelists claimed not to have time for facebook or twitter, for example, saying “that’s like not having time to use paper on the toilet.” He also got off a nice line about “peeing your trousers in winter” that I’ll just have to save for my next lecture.

My own talk was in an early morning session on mass incarceration, organized by Bill Pridemore and Bob Crutchfield on behalf of the American Society of Criminology. The papers were strong, the audience offered great insights and questions, and some supersharp journalists followed-up afterwards with the sort of penetrating questions that took me years to formulate.

And I guess that’s the challenge and the promise of good science communication. If a roomful of curious non-experts can somehow apprehend the crux of the biscuit at 8 am on a Saturday, there’s no reason that sites like TSP can’t do our bit to bring social scientific knowledge and information to broader public visibility and influence.

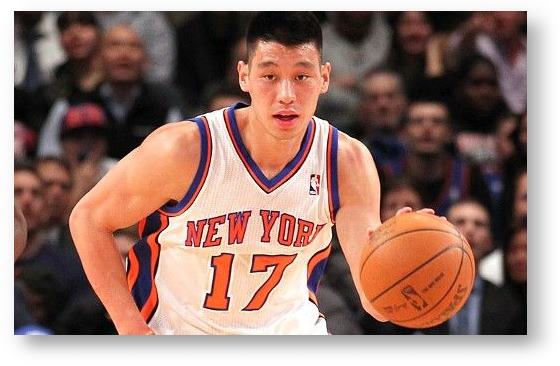

In the past few days there is one story I’ve been asked about more than any other in the news or current events—it involves the (unexpected) hot hand of undrafted NBA rookie Jeremy Lin of the New York Knicks. “What do you think?,” everyone wants to know. “You must have an interesting angle or two given your interest in race and sport, right?”

Well, I am fascinated. Indeed, my son Ben and I were intrigued enough to buy tickets to our first Timberwolves game in at least five years to see Lin and his New York team take on our local favorites Saturday night (led by another heralded rookie point guard Spaniard Ricky Rubio). It was quite a spectacle: over 20,000 fans (the most in Minneapolis since 2004, they said), more Asian Americans than I can ever remember seeing at a pro sports event, and some interesting commentary up in the nosebleed seats where we were perched. There was also a puzzling (if racially revealing) reference in the local paper the next day about a budding “international” rivalry between the two rookie playmakers. (I mean, Lin is from Palo Alto, after all.)

Still, most of my interest so far has been at Lin’s amazing play. The number of points and assists he posted in his first five games in the league was better than any other first five-game stretch of any player in NBA history. He led the Knicks to a comeback win here in Minnesota even when he was clearly exhausted from having played the night before in New York. On Valentine’s Day, he nailed a last second three-pointer for the win. I just love seeing great basketball. Check out any of his highlight clips on YouTube and you’ll see what I mean.

Thankfully, one of our TSP bloggers, C.N. Le, writing on The Color Line, has been able to maintain professional decorum and provide some sociological meaning and context for the Lin-sanity.

Le reviews some of the ground he covered in 2010 when he wrote when Lin was still playing for Harvard—how the ballplayer provides a counter to certain model minority stereotypes and expectations and in doing so is expanding the definition of success for Asian Americans. (Le’s even earlier post mentioned some of the racial stereotypes and slurs Lin has dealt with along the way as well.) But what I like most about the post is at the end, where Le is talking not about Lin but about colorblindness:

But as Asian Americans becoming increasingly common in these areas of U.S. popular culture, are we headed for a day when it is no longer a “big deal” when we see Asian American faces in the media, just like it’s taken for granted when we see White faces or Black faces? Ultimately, yes, that is the goal—for us as a society to no longer consider it “strange” or “unusual” to see Asian Americans in the media or in other prominent positions in U.S. social institutions.

Le goes on to point out—and this is the part I really like—that what we are talking about here is the concept of colorblindness, a concept that many of us race scholars actually tend to be quite critical about. It is a provocative reminder of what is good, right, and valuable about colorblindness as an ideal. But appropriately, Le also insists on reminding us—as he does over and over in his writings—of two points: (1) that we are still not there yet, and (2) to get there we actually have to be aware of race and racial inequalities and racism and vigilant in trying to resist them.

I’m not sure how aware Jeremy Lin is about any of this (though I wouldn’t put it past him. He’s not only doing amazing things on the court, he is clearly a very smart guy. In fact, as a friend of mine speculated today, one of the stereotypes Lin is laying bare is the old dumb-jock trope. Even in his “nerdy handshake” with other smarty-pants baller Landry Fields—seen below—Lin is showing that Ivy Leaguers can definitely hoop.) But I very much appreciate C.N. Le’s ability to draw out this broader social significance and use the power of the popular in service of making these vitally important sociological points about race and the struggle to move past race in contemporary American society.

![291402242_608acc3c7a[1]](https://thesocietypages.org/editors/files/2012/02/291402242_608acc3c7a1-219x330.jpg) Sociologist Eric Klinenberg’s Going Solo is garnering well-deserved attention in venues ranging from Fortune to Slate to This American Life, but his Rolling Stone article today is my favorite thus far.

Sociologist Eric Klinenberg’s Going Solo is garnering well-deserved attention in venues ranging from Fortune to Slate to This American Life, but his Rolling Stone article today is my favorite thus far.

Eric has assembled a terrific playlist for his new book — everything from Billy Idol’s Dancing with Myself to Beyonce’s Single Ladies. And you know that a researcher like Professor Klinenberg wouldn’t limit himself to the obvious hits. He unearthed nuggets like Tom Waits‘ “Better Off without a Wife” and Loudon (via Rufus) Wainwright’s One Man Guy, Morrissey’s “I’m OK by Myself” and Uggen’s “One-Way Love Dirge.”

OK, OK, I’m kidding about that last one. The spotify list makes for good fun and a great argument-starter (e.g., I’ve got a different take on “No Woman No Cry”), but the article and the book make a much bigger sociological argument. Eric is really telling a story of massive social change — the extraordinary rise of living along alone:

Until the middle of the 20th century, no society in human history had sustained large numbers of singletons. In 1950, for instance, only 4 million Americans lived alone, and they accounted for less than 10 percent of all households. Today, more than 32 million Americans are going solo. They represent 28 percent of all households at the national level; more than 40 percent in cities including San Francisco, Seattle, Atlanta, Denver, and Minneapolis; and nearly 50 percent in Washington D.C. and Manhattan, the twin capitals of the solo nation.

Check out the playlist and stay tuned (so to speak) for an upcoming office hours podcast with our own Arturo Baiocchi.

*photo by Tor Kristensen

David Denby’s polemic against smart-alecky new media types attracted a lot of, well, snarky reviews when it arrived in bookstores a few years ago. Of course, the First Amendment has protected all manner of speech about public figures since at least the Times v. Sullivan decision in 1964. Denby points to exceptions, but most of the serious journalists that I know seem almost constitutionally incapable of abusing such freedoms. In my view, the uglier snark story concerns not professional journalists, but the cultural transmission of snark in which all of us post breathlessly and nastily on social media.

David Denby’s polemic against smart-alecky new media types attracted a lot of, well, snarky reviews when it arrived in bookstores a few years ago. Of course, the First Amendment has protected all manner of speech about public figures since at least the Times v. Sullivan decision in 1964. Denby points to exceptions, but most of the serious journalists that I know seem almost constitutionally incapable of abusing such freedoms. In my view, the uglier snark story concerns not professional journalists, but the cultural transmission of snark in which all of us post breathlessly and nastily on social media.

It certainly seems easy to take shots at celebrities, politicians, and even our own friends and family with mean little missives on twitter or facebook. Watching indie darling Bon Iver on Saturday Night Live last weekend, for example, I wanted to post something clever about his descent through Coldplay territory and into Hornsby range (Christopher Cross won Grammys too, you know). After seeing Midnight in Paris, I felt a similar urge to tweet a line about Woody Allen’s real genius being reflected in somehow rehashing Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure with actors lacking Keanu Reeves’ emotional range. The trouble with such snark is that it isn’t based on any real thought or analysis — it is snark for snark’s sake. I hadn’t critically engaged Woody Allen or Bon Iver (much less Keanu or Coldplay) or even thought more than two seconds about it. I can’t fathom the motives here — are we in it for the “likes” and retweets? Do we feel better about ourselves when we rip the famous or successful?

Iggy Pop once said that “nihilism is best done by professionals” and so, I suspect, are such off-handedly cruel attacks. As an aspiring rock writer in the 1980s, I appreciated both the romantic humanism of Lester Bangs and the hyperliterate sneak atttacks of Robert Christgau. Mr. Christgau’s wicked/smart capsule reviews, were peppered with mean and clever phrases like “idolization is for rock stars, even rock stars manqué like these impotent bohos” (on Sonic Youth) or “the words achieve precisely the same pitch of aesthetic necessity as the music, which is none at all” (on Radiohead) or “As bubble-headed as the teen-telos lyrics at best. As dumb as Uriah Heep at worst” (on U2). The quintessential Christgau review? The fictitious two-word appraisal of Spinal Tap’s Shark Sandwich — the very definition of snark.

But Christgau also did real analysis, as in this rumination on the Eagles: “Another thing that interests me about the Eagles is that I hate them. “Hate” is the kind of up-tight word that automatically excludes one from polite posthippie circles, a good reason to use it, but it is also meant to convey an anguish that is very intense, yet difficult to pinpoint. Do I hate music that has been giving me pleasure all weekend, made by four human beings I’ve never met? Yeah, I think so. Listening to the Eagles has left me feeling alienated from things I used to love. As the culmination of rock’s country strain, the group is also the culmination of the counterculture reaction that strain epitomizes.”

Most of the tweets I see on, say, the death of Whitney Houston or a politician’s fall from grace aren’t nearly so reflective, even when smart people are tossing them off. As a criminologist, I’m often trying to cultivate a little reflection and empathy in my students, so that they see criminal behavior as human behavior — and the person convicted of crimes as more than the personification of a single, awful act. David Carr describes this duality with staggering clarity in telling his own story: “If I said I was a fat thug who beat up women and sold bad coke, would you like my story? What if instead I wrote that I was a recovered addict who obtained sole custody of my twin girls, got us off welfare and raised them by myself, even though I had a little touch of cancer? Now we’re talking. Both are equally true…”

Carr isn’t being snarky, he’s just an unflinching professional reporter trying to tell a complex story. One-sided snark, in contrast, simply “piles on” people at their weakest moments. I’ll confess that after seven years of blogging, I’ve probably written my share of thoughtlessly cruel comments. Even when the object of your derision could not possibly be hurt by it, haven’t you felt a little pang of regret after posting or repeating something petty, malicious, or unfounded? It feels, to me, as though I’d just binged on really unhealthy food or drink. Back when I was known to enjoy a beer or two during a flight delay, I recall getting some cheap laughs with an over-the-top Greta Van Susteren impersonation (don’t ask) at the Detroit airport. Though nobody registered any dissatisfaction (and Ms. Van Susteren seems to be doing just fine, thankyouverymuch), I still feel rotten about it three years later.

So for now I’ll stand with Denby — in our bermuda shorts, watering our respective lawns — and his old-fashioned assertion that mindless hair-trigger snark might somehow deplete us. If every cruel line in the snarkstorm represents an ugly little human transaction, is it so far-fetched to suggest that their collective weight might be dragging us down?

I don’t know if you’ve had a chance to read it yet or not, but last week, Kyle Green and I posted one of the first TSP white papers on the interrelationships between sport and politics in contemporary American culture. (https://thesocietypages.org/papers/politics-and-sport/).

Intended to coincide with the super bowl and in the middle of the republican primaries, the main point was to examine all of the ways in which sport and politics are intertwined, even if we don’t like it. We concluded that piece by saying that our goal was not necessarily to argue that the two should be separate but concluded that some might take it that way.

Well, what do you know but this week’s back page column in Sports Illustrated is a mock political campaign by columnist Phil Taylor to push for passage of a bill that would “ensure” the permanent “separation of sports and politics.”

http://sportsillustrated.cnn.

Taylor is clearly having fun with the piece, mostly at the expense of politicians who have pretended to be sports fans and men of the people. (Joe Biden, John Kerry, Newt Gingritch, Rick Santorum, and Mitt Romney all take shots). There are no great sociological insights here–just a number of great and revealing examples of the awkward, potentially combustable collusion of sport and politics in contemporary life.

My favorite part is Taylor’s speculation that this campaign might be one of the few arenas in which a bipartisan coalition in American politics might be possible. I love that line–both because it speaks to how deeply and broadly-held are our beliefs about the separation of sports and politics (“God bless any elected official who doesn’t pretend to care about the Super Bowl,” he writes) and as a commentary on how difficult it is to imagine Democrats and Republicans coming to consensus on anything these days.

My late mother-in-law was born and raised in Okinawa and came to the United States as an adult. She didn’t read a lot of English publications, but she swore by Dear Abby. She said read the column because Abby’s advice taught her what it meant to be a good American. I’ve thought about that a lot over the years, and I’ve often wished there were more such commonsense voices of decorum, belief, and behavior in our public discourse—never more so than right now.

Which brings me to the website “Yo, is this racist?” (yoisthisracist.com) by blogger Andrew Ti.

Okay, well, that’s not exactly accurate. I mean, I wouldn’t have put Ti in the “Dear Abby” category on my own. He and his website are often irreverent , sometimes offensive or downright vulgar, and just seem to be having too much fun most of the time. But that’s how Rachel Brahinsky, writing in Antipode described him: “Ti …mocks overt and subtle racism with comedy and brilliance, using a renovation of the old ‘Dear Abby’ format.”

Brahinsky explains:

Readers send in questions, and Ti tears them apart, mocks them, and applauds them for their insights. The exchanges range from goofy to deadly serious, and Ti has a tendency to curse a lot and use text-isms like LOL to reach his audience—and the consistency of his critique is highly uneven (sometimes he’s just name-calling, but that usually seems to come after receiving a raft of nasty racist emails from readers; the blog is his outlet).

But there is a lot of brilliance in the blog, and it generally comes at moments when Ti uses the space to redirect a reader’s question from the micro-moments of interpersonal racism to the socio-structural factors that bracket those moments.

I think that Brahinsky’s is a pretty accurate description and assessment, and in fact I had been meaning to write something on the site myself (my son had introduced me to it) ’til she beat me to the punch. I am especially convinced that Ti is at his best when he situates various comments, questions, and episodes in the context of larger racial hierarchies in the U.S. In doing so, he shows that not all comments and quotes are equal—and that things like context, who is speaking, and who is listening are crucial to the racial implications and effects of any given utterance or interaction. I also believe that Brahinsky is precisely on point about the challenges—and necessity—of using humor to get at racism, not only in the classroom but in the culture. Plus, I appreciated the quote from my former advisor George Lipsitz. Thanks, Rachel, for writing this up!