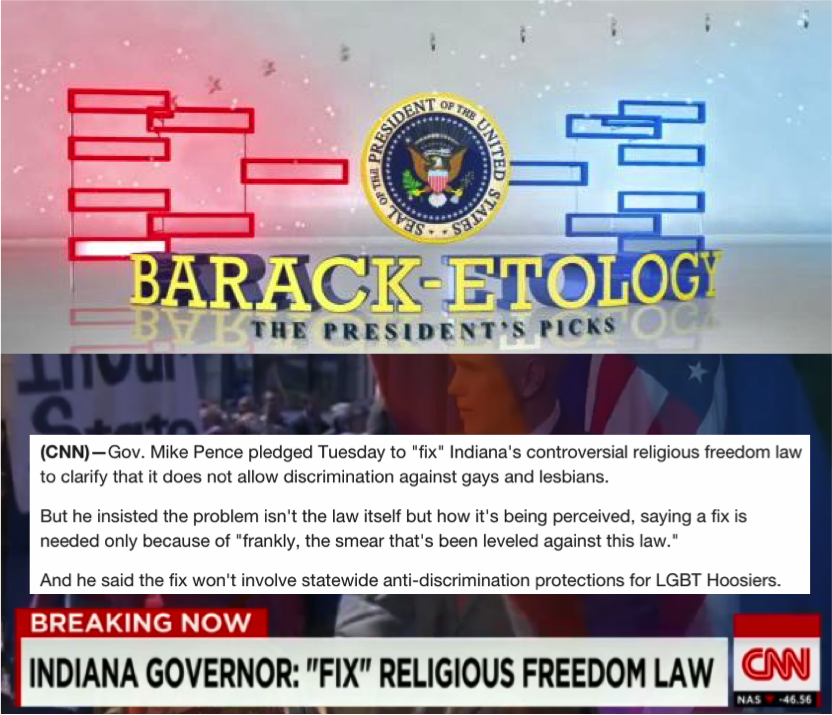

What to feature on the home page this week? How about some research on religion and society, since Passover and Easter are coming up? Or perhaps we should do something on LGBTQ discrimination, given the law that just got passed in Indiana (and a similar one Arkansas’s governor unexpectedly rejected). But maybe those stories are better framed sociologically in terms of protests and social movements, given all of the controversy that has surrounded it. Or does this actually require a religious analysis? After all, the legislation was called “The Restoring Religious Freedom Act.” Maybe, instead of playing our usual “Debbie Downer” role, we should just have some fun and find a piece on the Final Four, March Madness, and the whole spectacle of sport in modern society. (Though, truthfully, talking about college basketball as “spectacle” already feels like falling into familiar habits.)

If only we had a piece that brought all this together in one fell swoop. If only we had a piece that could connect the various dots of religion, rights and freedoms, LGBTQ discrimination, public policy and political protest, and mass-mediated, spectacle sports. And, can we get that before the high holidays are over?

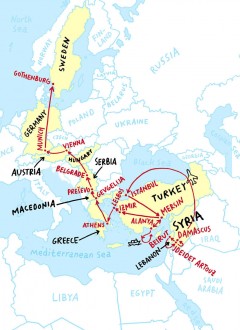

Actually, in a way we have such a piece, or at least the building blocks for one. I’m referring to the drama that is being played out right in front of us this very week in Indiana as Governor Mike Pence, under heavy pressure from those calling for the NCAA to pull its headquarters (if not the Final Four itself) out of the state, scrambles to “fix” the legislation his legislature just approved. What a story! Here we see religion and sexuality come right up against each other, how the Constitutional “rights” of some are balanced (or not) against the Constitutional “freedoms” of others. Here we can observe how institutional power plays out against political protest and passionate social movements, as well as try to ferret out where the mass media and corporate interests with such stakes in March’s Madness will come down. Here we can watch as that seemingly fun, apolitical realm of sport suddenly gets pulled into a very high profile, very controversial, very political debate. And it is all happening during one of the most sacred weeks of the year. (I was talking about the religious folks when I first wrote that but I guess I shouldn’t leave the sports fans out–especially since I count myself, for better or worse, as a member of both of these passionate communities.) It’s almost too good to be true–from a sociological, home page-type point of view.

Of course, we don’t really have that story—or should I say that analysis—yet. If you are working on that and have something to share, please send it along. Sociological analysis doesn’t just write itself. In the meantime, let me share two smaller pieces that might help provide some frame and context.

One is a “TROT!” (There’s Research on That!) piece pulling together some great sociological research on the squishiness (that’s our technical term) of laws regarding religious freedom and the rights of refusal–that is, legal attempts to codify which forms of discrimination on the basis of race, religion, or sexual orientation are allowed; whose rights and freedoms are inscribed and institutionalized; and the problems with trying to enforce these laws and statutes in actual social life. So, while nearly half of all U.S. states have religious freedom and right of refusal laws on the books, most also include codicils specifying that businesses cannot discriminate on the basis of race, religion, or sexual orientation. How Indiana and Arkansas’s laws will—or will not—open the door for business owners and others to close theirs, refusing service to LGBTQ-identified citizens, should be interesting and the research compiled in this piece should help you understand the complexities and perhaps even anticipate how the drama will unfold.

Second, I’d like to direct you to the white paper Kyle Green and yours truly wrote for the TSP politics volume a little while back: “Sport and Politics: Strange, Secret Bedfellows.” The way in which politics and sport are colliding in Indiana right now is nothing new or novel. Too often when we are watching sports we don’t even see the politics being played out right in front of us. And too many of us are too quick to cynically dismiss struggles in the politic realm as mere games that don’t matter anymore. This stuff matters, no matter what side you are on or which team you are rooting for.