The following was written by our colleagues Kendra Dupuy, James Ron, and Aseem Prakash, and it was originally published on the site OpenDemocracy.net. It provides a provocative look at the local involvement of international NGOs in projects around the world. You’ll see below that Ron has written an addendum in response to insightful critiques and comments from his network, and I hope that you’ll add your own thoughts in the comments.

The U.S. elections are now over, but crucial foreign policy decisions remain on the table. Foreign aid was hardly discussed in the U.S. presidential elections, and neither Romney nor Obama said whether American assistance should still be funnelled through non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

This neglect is unfortunate, given the current global backlash against externally supported NGOs. The time has come for western and international donors to reconsider the way in which they support human rights, democracy, gender equality, and other liberal causes in the developing and former Communist world. Supporting liberal NGOs can be useful, but it must be done carefully and modestly, lest it undermine the same agendas it seeks to promote.

International solidarity is a wonderful idea, and the notion of transferring resources from North to South for good causes is morally attractive. The mechanics of doing this properly, however, are far more complex.

Here’s the background.

For years, it was received wisdom in western and international donor circles that aid to local civil society in the developing and former Communist world would promote democracy and other liberal ideals. In some cases, that has been true. In others, however, foreign aid has provoked a real backlash.

Today, many governments and some citizens are enraged by foreign-funded NGOs, and they are mobilizing conservative ideas and policies to strike back. In these cases, international assistance to liberal NGOs has become part of the problem, rather than part of the solution.

Consider Russia, where new, anti-NGO legislation is ringing alarm bells at home and abroad. If NGOs want to engage in political activities, a broad category that includes any attempt to change state policy, they must now register with a special agency before receiving foreign money, declare themselves “foreign agents,” engage in onerous reporting, and prepare for unannounced audits. To drive the point home, Russia recently ordered official U.S. aid workers to leave the country and stop funding local NGOs.

In Israel, similarly, legislators have debated rules close to Russia’s, and may yet turn them into law. In Canada, a former bastion of liberal thinking, the government has bitterly protested foreign-funded environmental groups, claiming, as always, that they undermine national sovereignty.

Other examples include Ethiopia, a darling of the western aid community, and India, often hailed as the world’s largest democracy. In Africa, according to our research, over one-third of countries, since 1995, have passed new laws, or tightened old ones, restricting foreign aid to NGOs and/or limiting the work of international groups.

Why this backlash?

Both democratic and authoritarian governments are increasingly incensed at western donors’ attempts to reshape local politics and values through NGOs. In some cases, they have successfully mobilized conservative politicians, social movements, and organizations, many of whom are angered by the very same thing.

Both democratic and authoritarian governments are increasingly incensed at western donors’ attempts to reshape local politics and values through NGOs.

Governmental opposition matters, because the local NGO community is highly dependent on foreign money. States can easily twist the screws by blocking—or threatening to block—the aid pipeline.

Hold on, however. Aren’t developing and former Communist countries too poor to support a local NGO community? Isn’t external aid utterly necessary?

In some cases, yes. In other cases, however, the answer is no.

Israel, for example, is a relatively rich country, but over 90% of its local human rights activities, according to a scholarly survey, are funded from Europe and America. And according to our survey of 235 human rights workers from 61 countries, local experts’ median estimate of rights groups receiving substantial foreign aid is 75%. There is no statistical correlation, moreover, between these estimates and country wealth, as measured by per capita GDP.

Some countries, in other words, are sufficiently wealthy to support local NGOs. And most countries have a strong charitable tradition of some kind. The problem, however, is that the kinds of issues that liberal NGOs work on don’t attract many donations from local individuals, communities and businesses in the developing world. This makes local NGOs vulnerable to cut-offs in aid, and exposes them to governments arguing that local NGOs are agents of foreign forces.

How did this happen?

During the 1990s, many countries experienced a dramatic upsurge in voluntary activism, and international donors understandably responded with enthusiasm. Donors’ goals, for the most part, were laudable. The money was meant to help local NGOs promote democratization, markets, gender equality, good governance, and respect for human rights.

In some cases, this support helped an already-vibrant civil society grow stronger. In other instances, however, money from the outside turned civil society into a vulnerable, externally oriented community.

Over time, many local NGOs became top-down groups nourished from abroad, rather than local products of a popular, grass-roots civic movement. Understandably, foreign-supported NGOs began to adopt the issues, language, and structures their foreign donors wanted, rather than those preferred by local people.

Few realize that while foreign aid gives NGOs the wherewithal to operate independently, it also undermines their incentives to generate local revenue. Like governments afflicted with the so-called resource curse, foreign aid to NGOs reduces the need to raise money locally. Why raise small sums at home when so much more is available abroad?

Tragically, plentiful foreign aid also promotes “briefcase NGOs,” fake groups that exist only on paper and provide few services. In one recent study, surveyors discovered that some 75% of registered NGOs in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, did not really exist. According to our research, there are reasons to suspect that a similar rate obtains in Ethiopia.

More worryingly, foreign aid inadvertently undermines NGOs ties to local populations, handing angry governments an opportunity for successful crackdowns. In 2010, for example, the Ethiopian government’s new anti NGO law, the Charities and Societies Proclamation, blocked foreign funded groups from working on Ethiopian human rights and democracy. Shortly thereafter, most briefcase and rights groups disappeared, while most surviving NGOs stopped working on human rights altogether.

The Ethiopian public, sadly, proved unable or unwilling to help. Closure of 90% of the country’s 125 local rights groups prompted few popular demonstrations, and not many ordinary citizens offered financial support.

Some Ethiopians didn’t demonstrate or contribute because they feared government retaliation; Ethiopia has become very repressive of late. Others, however, were unmoved by local NGOs’ plight. As one report argued, Ethiopians have come to view NGOs as entities who give them money, not as groups needing their help. Many Ethiopians will help family and strangers in need, and some will donate their time, money, and effort to charitable causes. Local NGOs working on liberal causes, however, are generally viewed as something for outsiders, rather than Ethiopians, to support.

Generous foreign funding of local NGOs is a classic example of good intentions causing perverse outcomes. International solidarity is a wonderful idea, and the notion of transferring resources from North to South for good causes is morally attractive. The mechanics of doing this properly, however, are far more complex. Creating or sustaining local NGOs from outside, with little local support, is bad public policy.

There are always exceptions, but civil society should, ideally, remain a bottom-up affair. Outsiders can help, but they should do so carefully and sparingly, lest their embrace prove lethal.

You can’t buy love, and you can’t buy a vibrant civil society either.

Update

In response to “insightful critiques by pro-democracy colleagues in Israel,” one of the authors, James Ron added the following on 11/16/12, and Kendra Dupuy would like to endorse his additional statement:

I am in no way endorsing the conservative crackdown on NGOs by the Russian, Ethiopian, Israeli, Indian, or other governments. On the contrary. I think those governments are behaving in an entirely illiberal manner, and should be condemned for so doing in the strongest possible terms. I have long been a supporter of Israeli human rights NGOs, both from inside and outside the country. I am also more than willing to acknowledge that in many cases, including Israel, conservative forces are generously funded from abroad. Any move to suddenly cut local liberal groups off from foreign funds is likely to prove disastrous for Israeli democracy and, more importantly, for Palestinian rights.

At the same time, I don’t think the only or best international response to the new conservative onslaught on local NGOs is to simply insist that the international aid pipeline must continue. Instead, international donors should start devoting money, effort and time to figuring out how to encourage, enable, and empower local NGOs to raise more money locally, either from small, individual contributions by members and/or supporters,or from larger sources, such as businesses, charitable associations, and wealthy individuals. According to many of the rights-based NGO activists I’ve interviewed for my Rights-Based Organization project (see www.jamesron.com),local human rights NGOs in the developing world often lack the capacity, skills, and incentive to raise money locally. This needs to change.

I am also more than willing to acknowledge that some important social justice issues may never receive local funding. In Mumbai, for example, I met a few years ago with a local NGO working for the rights and welfare of local prostitutes—many of whom had been trafficked—and was convinced by one of its leaders, who explained that the sex trade was so locally condemned that Mumbai-based donors were unlikely to ever provide much financial support. Similarly, it may be that Israeli human rights groups will never be able to raise sufficient local money to protect Palestinian rights; Jewish Israeli society, especially in its current form, may be too unwilling to ever go there.

The decision as to whether a cause, issue, or agenda is wholly un-fundable from local sources, however, should not be made lightly, and without strong evidence. All too often, I believe, that argument is made without really trying another route.

So yes, there will always be cases where local NGOs are going to need foreign money. And yes, international aid should continue to the local NGO sector. However, this international aid money should be spent in such a way so that local NGOs are empowered and encouraged to eventually raise more money locally, so that some form of self sufficiency can eventually be achieved, whenever possible.

Kendra Dupuy is in the political science program at the University of Washington and is a researcher with Norway’s International Peace Research Institute, James Ron is a political scientist at the University of Minnesota, and Aseem Prakash is a political scientist at the University of Washington.

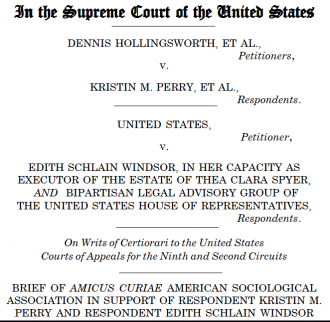

Remember how I said it was the worst spring break ever? Well, I’m usually not one to dwell on the dismal, but sometimes circumstances dictate the mood. I’m speaking, of course, of Justice Antonin Scalia’s comment in the Supreme Court hearings on the U.S. law defining marriage that “there’s considerable disagreement among sociologists as to what the consequences of raising a child in a single-sex family, whether that is harmful to the child or not.”

Remember how I said it was the worst spring break ever? Well, I’m usually not one to dwell on the dismal, but sometimes circumstances dictate the mood. I’m speaking, of course, of Justice Antonin Scalia’s comment in the Supreme Court hearings on the U.S. law defining marriage that “there’s considerable disagreement among sociologists as to what the consequences of raising a child in a single-sex family, whether that is harmful to the child or not.”