In the past few days there is one story I’ve been asked about more than any other in the news or current events—it involves the (unexpected) hot hand of undrafted NBA rookie Jeremy Lin of the New York Knicks. “What do you think?,” everyone wants to know. “You must have an interesting angle or two given your interest in race and sport, right?”

Well, I am fascinated. Indeed, my son Ben and I were intrigued enough to buy tickets to our first Timberwolves game in at least five years to see Lin and his New York team take on our local favorites Saturday night (led by another heralded rookie point guard Spaniard Ricky Rubio). It was quite a spectacle: over 20,000 fans (the most in Minneapolis since 2004, they said), more Asian Americans than I can ever remember seeing at a pro sports event, and some interesting commentary up in the nosebleed seats where we were perched. There was also a puzzling (if racially revealing) reference in the local paper the next day about a budding “international” rivalry between the two rookie playmakers. (I mean, Lin is from Palo Alto, after all.)

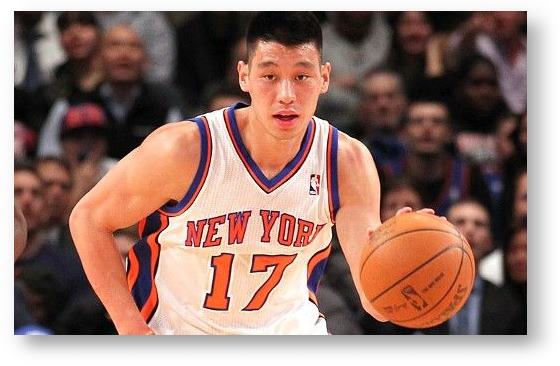

Still, most of my interest so far has been at Lin’s amazing play. The number of points and assists he posted in his first five games in the league was better than any other first five-game stretch of any player in NBA history. He led the Knicks to a comeback win here in Minnesota even when he was clearly exhausted from having played the night before in New York. On Valentine’s Day, he nailed a last second three-pointer for the win. I just love seeing great basketball. Check out any of his highlight clips on YouTube and you’ll see what I mean.

Thankfully, one of our TSP bloggers, C.N. Le, writing on The Color Line, has been able to maintain professional decorum and provide some sociological meaning and context for the Lin-sanity.

Le reviews some of the ground he covered in 2010 when he wrote when Lin was still playing for Harvard—how the ballplayer provides a counter to certain model minority stereotypes and expectations and in doing so is expanding the definition of success for Asian Americans. (Le’s even earlier post mentioned some of the racial stereotypes and slurs Lin has dealt with along the way as well.) But what I like most about the post is at the end, where Le is talking not about Lin but about colorblindness:

But as Asian Americans becoming increasingly common in these areas of U.S. popular culture, are we headed for a day when it is no longer a “big deal” when we see Asian American faces in the media, just like it’s taken for granted when we see White faces or Black faces? Ultimately, yes, that is the goal—for us as a society to no longer consider it “strange” or “unusual” to see Asian Americans in the media or in other prominent positions in U.S. social institutions.

Le goes on to point out—and this is the part I really like—that what we are talking about here is the concept of colorblindness, a concept that many of us race scholars actually tend to be quite critical about. It is a provocative reminder of what is good, right, and valuable about colorblindness as an ideal. But appropriately, Le also insists on reminding us—as he does over and over in his writings—of two points: (1) that we are still not there yet, and (2) to get there we actually have to be aware of race and racial inequalities and racism and vigilant in trying to resist them.

I’m not sure how aware Jeremy Lin is about any of this (though I wouldn’t put it past him. He’s not only doing amazing things on the court, he is clearly a very smart guy. In fact, as a friend of mine speculated today, one of the stereotypes Lin is laying bare is the old dumb-jock trope. Even in his “nerdy handshake” with other smarty-pants baller Landry Fields—seen below—Lin is showing that Ivy Leaguers can definitely hoop.) But I very much appreciate C.N. Le’s ability to draw out this broader social significance and use the power of the popular in service of making these vitally important sociological points about race and the struggle to move past race in contemporary American society.

Comments 1

C.N. — February 16, 2012

Thanks for the kind words, Doug. The Jeremy Lin phenomenon is a great sociological topic on so many levels and across multiple angles. I'm glad you and your son had fun doing your own 'fieldwork' in studying it!