Image by Jordyn Wald.

“Time to BeReal. 2 mins left to capture a BeReal and see what your friends are up to!” This is the daily notification users receive on BeReal, an app designed to promote authenticity by prompting users to share unfiltered photos from both the front and back cameras at a random time every day. BeReal attempts to constrain users to post within a 2-minute window with zero retakes, but many users circumvent these constraints by delaying posts or retaking their photos. The one caveat? If a user chooses to retake photos, they are labeled as “retakes” and your followers can see this label. So, how “real” are users truly being?

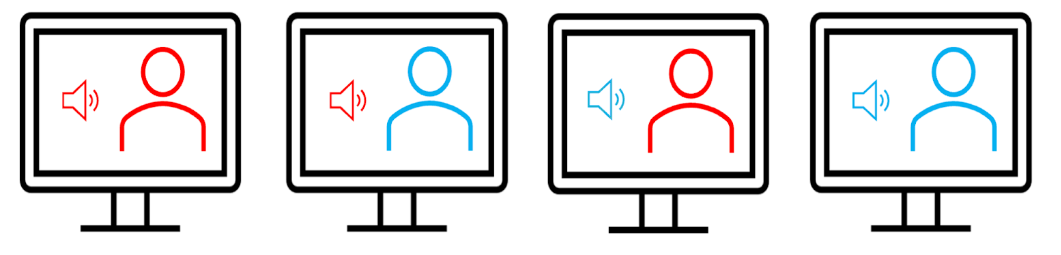

Through a series of interviews with BeReal users, Annika Pinch and colleagues set out to understand how young adults perceive and define their own authenticity on BeReal over time, as well as how they assess the authenticity of others on the app. BeReal was initially understood by participants as a refreshing alternative to highly curated social media platforms, encouraging authenticity through its posting constraints. However, over time, participants began to observe a shift toward performative behaviors, mirroring patterns seen on other platforms.

For example, participants would actively resist BeReal’s constraints of posting within a 2-minute window by delaying posts to capture more interesting moments in their day. Ignoring the app’s initial notification and delaying posting became more socially acceptable. Even so, participants still grappled with how to evaluate the authenticity of others. Some viewed retakes or delayed posts as inauthentic, while others believed curated posts could still reflect genuine self-expression. As one participant said, “I hate her BeReals. I’m like, You’re defeating the whole purpose of the platform’ and it annoys me to see it… she’s unaware that we can see that she’s retaken it nine times.”

Authenticity on BeReal is shaped by both platform constraints and social norms that emerge among users. Pinch and her colleagues found that while social media apps can push for authenticity through strict platform design, eventually, these features will clash with users’ need for control of how they present themselves online. For sociologists, this study offers another example of the enduring relevance of Erving Goffman’s insights on the presentation of self and impression management.