Contesting individual’s claims to Indigenous ancestry is nothing new; a notable example is Elizabeth Warren’s ancestry testing and Donald Trump’s repeated “Pocahontas” jeers. Proving authentic group heritage is something many Americans never think about, but such dynamics are common for Indigenous persons.

The labels, “Native American,” “Indigenous,” and “American Indian,” are social constructions rooted in the story of colonization. Indigenous populations in present-day United States were subject to state policies and institutions that lumped many different groups into the label, “Native American.” As a legacy of these policies, people have to provide proof of Native American ancestry to be considered official tribal members. In new research published in Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, Dwanna L. McKay explores how Indigenous people draw on different strategies to navigate these complicated systems of belonging and proving identity.

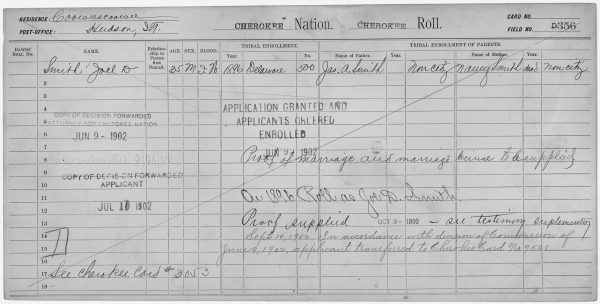

Interviewing 45 Native American participants, McKay describes two dominant methods they use to defend their identity as authentic Indigineous Peoples. First, there is “blood quantum,” a term that refers to how much Native ancestry or family a person can point to in their family tree. The other common way to display authenticity is producing one’s “Indian Card,” a certificate that some Indigenous people receive as proof of their heritage. For several interviewees, these cards not only represent a structural and political qualification, but also hold cultural and personal significance.

Of course, blood quantums and Indian cards are specific to Native Americans; members of other races in the United States do not have to similarly prove their ancestry or identity. This distinct picture is a product of colonialism and the subsequent categorization, marginalization, and isolated Indigenous populations. Today, such history has affected how people experience race and negotiate Indigenous authenticity.