When we talk about reproductive choices and regulations, women are generally at the center of these discussions. However, this hasn’t always been the case. In post-war India, the government changed its approach to population control by targeting men in birth control campaigns. Using archival materials from 1960-1977, Savina Balasubramanian analyzes this shift in family planning strategies. The government’s strategy relied on specific conceptions of masculinity, fatherhood, and men’s roles in families.

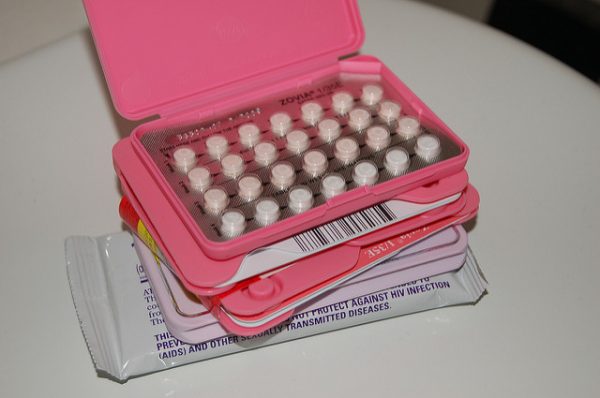

Balasubramanian explored archival records to show how social scientists, doctors, research donors, and state officials discussed population control. The “clinic model” of 1950s India primarily targeted women, but at the end of this decade scientists began to focus on men because they saw men as the decision-makers in families. They assumed that men were more likely to be literate and educated in rural and poor communities. Further, because men held more power in many families, officials worried there could be backlash if women were approached before their husbands. Their concerns were not just about men, though. Stereotypes about poor women as irresponsible led some scientists to argue that women could not be trusted to take contraceptive pills that required time-tracking.

To get men on board, scientists and state officials used masculinity norms — specifically associating men with rationality — to promote what Balasubramanian calls, “reproductive rationality.” In other words, contraception was framed as an economic issue that required calculation and forethought by the head of the family, assumedly the husband. The government also led “mass vasectomy camps,” which were festival-like affairs, and those who participated often received household items or money as incentives. However, due to political circumstances, this approach to birth control did not last. This approach — in which policymakers viewed men as responsible for birth control and gave them the power to make choices for their families — is particularly interesting when compared to current approaches to birth control. Today, policymakers are far more likely to assign primary responsibility to women, yet regulate their choices through legislation.

Comments