Dear Cyborgology Readers, we want you to write for us!! In our first ever thematic CFP, we invite guest posts about Cameras and Justice. This theme is broad in scope and we encourage you to put your own spin on it.

If you have an idea, pitch us. If you have a full post, send it our way. We will be taking submissions on this theme until mid June.

Posts are generally between 500-1500 words. Authors should write in a clear and accessible style (think upper-level undergraduate or well read non-academic). We welcome traditional text based essays, image based essays, and art pieces.

To get the brain juices flowing, here are a few pieces on Cameras and Justice from the Cyborgology team:

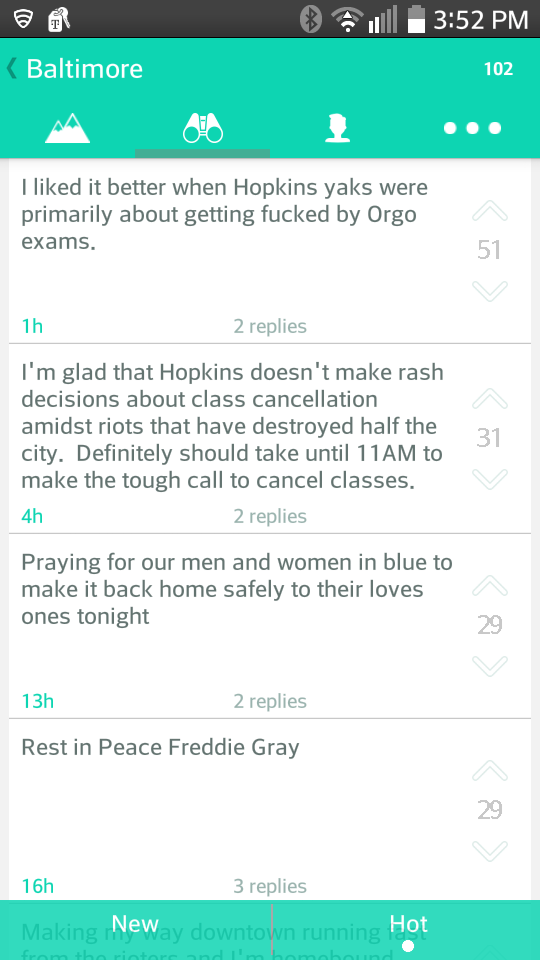

Cameras on Cops Isn’t the Same as Cops on Camera

ACLU Mobile Justice App: Channeling Citizen Voices

Sousveillance and Justice: A Panopticon in the Crowds

Surveillance from the Clouds to the Fog

Other riffs on this theme could include children’s privacy, tourism, unsolicited dick pics, structural oppression aided by the rhetoric of authenticity, and much, much more.

For submissions, questions, and proposals, email co-editors David Banks (david.adam.banks@gmail.com) and Jenny Davis (jdavis11474@gmail.com) using the subject line “Cameras and Justice.”

Remember that Cyborgology (for better or worse) is an all volunteer effort and we cannot pay for writing.

Headline Pic: Source