The Washington Post ran an article last Sunday about the Air Force’s new surveillance drone. The bot can hang in the air for weeks, using all nine of its cameras to provide a sweeping view of a village. Its a commanding officer’s dream come true: near-total battlefield awareness. Recording the data however, is only half of the battle. This vast amount of real-time data is almost incomprehensible. No one is capable of making sense of that much visual data unaided by some sort of curation device. There is an entire industry however, focusing on providing viewers with up-to-the-second live coverage of large, complex environments: sports entertainment.

The Washington Post ran an article last Sunday about the Air Force’s new surveillance drone. The bot can hang in the air for weeks, using all nine of its cameras to provide a sweeping view of a village. Its a commanding officer’s dream come true: near-total battlefield awareness. Recording the data however, is only half of the battle. This vast amount of real-time data is almost incomprehensible. No one is capable of making sense of that much visual data unaided by some sort of curation device. There is an entire industry however, focusing on providing viewers with up-to-the-second live coverage of large, complex environments: sports entertainment.

Pro sports have always been on the cutting edge of video recording. Being able to show an entire football field and, with a swift camera change, immediately shift focus and follow a fast-moving ball into the hands of a running receiver. The finished product is a series of moving images that provide the most pertinent data, at the right scale, as it happens.

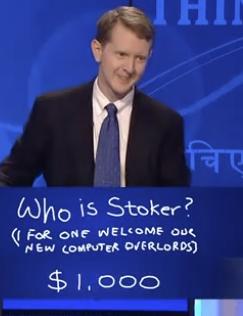

The Pentagon is adapting ESPN’s video tagging technology to make sense of battlefield surveillance. Need a replay of every car bomb detonated via cell phone in a neighborhood? Its as easy as replaying Brett Farve’s last three incomplete passes. Now that the data is organized into piles, its still relatively unmanageable. Imagine a Google search result that didn’t rank by relevance. Almost worthless.

In order to fix this problem, military analysts turned to a media phenomena that has mastered the art of finding relevance where there is none: Reality TV. Using similar editing and searching techniques, generals can call up the best surveillance coverage.

These video management systems are a defining characteristic of what we have come to call “The Information Age.” Important global institutions and resources are built and maintained using identical technologies and organizational schemes. In other words, state surveillance, professional sports, war, entertainment, prisons, and reference materials are all beginning to look like each other: similar means to different ends.

This may seem like a moot point. After all, corporations have always swapped seemingly unrelated business practices. Taylorism, the second-by-second regimentation of workers’ movements, has spread from Ford’s factories to McDonald’s kitchens. What gets scary, is the simple laws that drive the complexity of it all. As Steven Levy writes in the latest issue of WIRED,

“Today’s AI doesn’t try to re-create the brain. Instead, it uses machine learning, massive data sets, sophisticated sensors, and clever algorithms to master discrete tasks. Examples can be found everywhere: The Google global machine uses AI to interpret cryptic human queries. Credit card companies use it to track fraud. Netflix uses it to recommend movies to subscribers. And the financial system uses it to handle billions of trades (with only the occasional meltdown).”

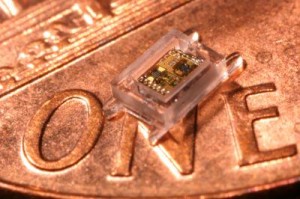

These algorithms are understood by few, but are relied upon by billions. They fight our wars, cure our diseases, and entertain us on Sunday nights. The “occasional meltdowns” can only be seen by those that understand the most complex of codes. AI won’t be contained in a single physical being, it’ll be in the cloud. Our collective fears over our self-aware machines rising up against us may gives us too much credit. They only need to fail at their own assigned tasks in order to win.

Manipulation and willful ignorance of these systems on the part of dominant groups may become the new method of control. Just as a teenagers blame poor cell phone reception for not calling their parents on time, a government can point toward burdensome upgrades needed to prevent the inevitable false-positives of automated surveillance. The teenager and the government use the limits of technology to negotiate increased power.

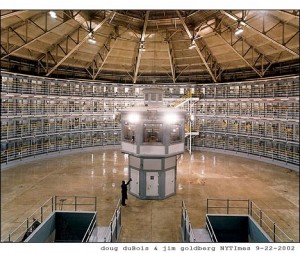

Bentham’s panopticon worked because prisoners could not see whether or not they were being watched by guards. In the twenty first century, the central tower is never manned, it is automated. Foucault reminds us that the state works much like the panopticon, but what would he say about a nation surveilled by learning networks? It no longer matters if the tower is manned or not because everything is recorded and available for instant replay.

Bentham’s panopticon worked because prisoners could not see whether or not they were being watched by guards. In the twenty first century, the central tower is never manned, it is automated. Foucault reminds us that the state works much like the panopticon, but what would he say about a nation surveilled by learning networks? It no longer matters if the tower is manned or not because everything is recorded and available for instant replay.

This over-surveillance will become a part of an individual’s daily risk mitigation. This has already begun in counties that have installed red light cameras at busy intersections. The citizens of war-torn countries will experience much greater consequences than expensive traffic tickets. They may be subject to a perpetual surveillance that combines the inscrutable detail of sports coverage, with reality TV’s fetishistic fascination of the mundane.

David A. Banks is a Science and Technology Studies M.S./Ph.D student at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. You can follow him on twitter: @da_banks