Reposted from Peasant Muse.

What does the term ‘cyberspace’ mean? Does this Gibsonian construct adequately fulfill the task, currently asked of it by many, of defining the digital/physical realm interaction in terms of its scope and function?

Attempts to frame new social interactions spurred by digital innovations in communication, documentation and self-actualization (just to name a few) generally encounter problems of word choice when describing the effects these advancements bring to our growing conceptions of reality. Literary terminology, often built upon antiquated notions reconfigured to suggest a potential or future state of being, sometimes suits the purpose of analogy when looking at these phenomena. Yet there always comes a time when our understanding of an event or construction of reality demands that we re-evaluate our word choice, lest our future analytical efforts be hindered by its, perhaps, outmoded or misleading operation. PJ Rey and the internet persona known as Mr. Teacup produced just this sort of re-evalutation of the term mentioned above, cyberspace, through two excellent pieces titled ‘There is no Cyberspace‘ and ‘There is Only Cyberspace’, respectively written.

PJ Rey argued that the term cyberspace, first coined by William Gibson in the short story ‘Burning Chrome’ and defined as a ‘consensual hallucination’, is deeply problematic in describing our contemporary social web because the web is neither consensual nor a hallucination. Thanks to the ubiquity of smart phones, pervasive documentary practices (something Nathan Jurgenson calls the ‘Facebook Eye‘) mean that even if someone does not participate in the social web their actions are nonetheless captured by it to some degree, thus shaping our actions on the individual and societal level. Many of us cannot control the degree to which this ‘Facebook Eye’ documents our actions (Could you stop every friend from making comments or posting pictures of your embarrassing moment from last week’s party? What about last year’s party?) making the web far from a consensual space. In many ways, because the web is not consensual it is also not a fantastical or a hallucinatory space either. It is a part of reality- the web is as real as reality itself. Actions taken offline impact online relations and vice-versa, allowing Rey to state that, “causality is bi-directional. We are all part of the same human-computer system.”

For Rey, ‘cyberspace’ is merely the continuation of dualist thinking inherited from the Western philosophical conception of the mind-body separation. Because the web always held a dialectal relationship with the physical world, Rey suggests that new vocabulary be created to more accurately explain the web/reality interplay, the augmented reality encompassing it all.

Affirming several of Rey’s assertions through a decidedly different analytical embrace, Mr. Teacup first dissects what he calls ‘augmentism’, a view attributed to the stance taken by Rey and others who write on the Cyborgology blog, before tackling the main issue at stake in the piece; what if there is no reality and only cyberspace? Teacup expresses a very nuanced critique in both sections of his response, one that makes a compelling yet, ultimately, flawed case for why augmentism and augmented reality claims fall flat.

Let’s begin with the presentation of augmentism. Teacup states that, “One thing that seems to be often implied is that digital dualism leads to exaggerated fears and anxieties, and augmented reality does not…augmentism effects a kind of naturalization or even domestication of technology.” He goes on to bring up the example of parents concerned with their child spending too much time playing World of Warcraft. While on face, the concern expressed by the parents would appear to enforce a digital dualist perspective of reality (Our son is spending too much time in the virtual world and ignoring the real world), Teacup accurately demonstrates that an ‘augmented’ perspective is actually at work as the parents are essentially stating that while the son may only feel like he’s in a virtual world, he is, in fact, very much a part of the real world and that ignoring real world concerns to play immersive games has impact. The parents concern reflects a belief in the dialectal relationship between the web and reality- a conception Rey argues for in his piece.

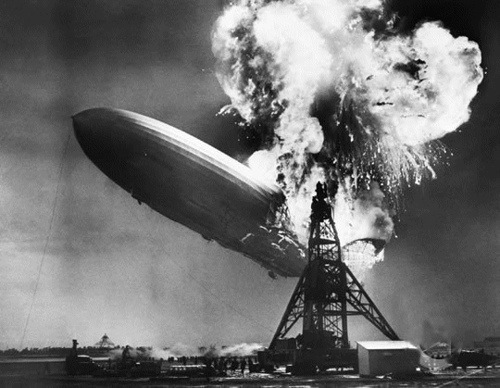

“Many moral panics are centrally concerned with the threat of confusing fantasy for reality,” writes Teacup, who later adds, “by this definition, the criticism of moral panics is itself a moral panic.” When Rey criticizes conceptions of reality rooted in a digital dualist discourse (like those espoused by the media concerning issues of internet addiction, violence in video games, etc…) he is engaging in a moral panic that is similar to the moral panics criticized in the first place. Yet Rey plays the trump card in asserting that there is no other space, no other fantasy world or virtual reality, for a digital dualist moral panic to build upon- there is no ‘alternate world’ that can be confused for reality because the web is as real as reality itself. The augmentist perspective, with its soothing naturalization of technology, presents a conception of reality in which the web seamlessly integrates and becomes a part of the everyday. One can’t have panic over frictional issues between the web and the real- the web is real so there is no friction and thus no panic.

Why? Because, as Teacup asserts in the second-half of his argument, there is an alternative between a dualist construction of reality, embodied by the mind-body debates, and an ‘augmented’ perspective of reality (Teacup calls this an ’embodied cognition’); there is the Lacan inspired ‘antagonistic opposition’ perspective. He writes, “to put it another way, our subjective self-consciousness feels like it has been grafted on, and sits in an uneasy relationship with the body.” As such the self exists in some degree of friction with the body, making augmentist claims impossible to assert. In denying the hybridity involved in ‘antagonistic opposition’, Rey ignores what Teacup labels the “simultaneously horrifying and compelling” nature of the modern cyborg. This is why Rey must refute the term ‘cyberspace’- to accept its existence would be to face the traumatic reality head on.

The reason Teacup makes such a compelling argument is that he attacks Rey’s ‘augmented reality’ conception at its assumed weakest point; the idea that web/reality dialectal relationships, through their interplay, are devoid of friction that could lead to panic. Yet I’m not sure that is an accurate assessment on the workings of an augmentist perspective. For example, there are questions related to the degree of permeation the digital wave of augmentation holds on any given space or situation. I live in Oregon and it is entirely possible for me to drive into a vast forest and lose all cellular connection, making my Galaxy S phone (my personal connector to the ‘Facebook Eye’) useless in documenting my experience. Say I go on a hike and see an amazing waterfall. When I return home, reentering the potential gaze of the ‘Facebook Eye’, the composition of my self is asynchronous to the self connected to and expressed through the web. I could remedy this asyncronicity by posting an update, or perhaps uploading and posting photos I took of the hike with my old point-and-shoot camera. But, I may choose not to post an update or upload photos. If I never tell a single person about my hike, then no matter how good the ‘Facebook Eye’ becomes it will always possess an asynchronous composition of my identity as compared to the lived experience. Smart phones and digital platforms make documenting life very easy (even non-consensual, as Rey observes), but in this ease I am reminded of the Philip K. Dick quote from ‘A Scanner Darkly’:

“What does a scanner see? he asked himself. I mean, really see? Into the head? Down into the heart? Does a passive infrared scanner like they used to use or a cube-type holo-scanner like they use these days, the latest thing, see into me—into us—clearly or darkly? I hope it does, he thought, see clearly, because I can’t any longer these days see into myself. I see only murk. Murk outside; murk inside. I hope, for everyone’s sake, the scanners do better. Because, he thought, if the scanner sees only darkly, the way I myself do, then we are cursed, cursed again and like we have been continually, and we’ll wind up dead this way, knowing very little and getting that little fragment wrong too.” (185)

This, to me, is the main conundrum in trying to assert that the web is reality. We must address this issue of whether or not the ‘Facebook Eye’ operates as a scanner darkly or a scanner clearly when engaging in pervasive documentation. If it indeed operates as a scanner darkly, then there can be no denying the presence of friction in the web/reality interplay found in an augmented reality.

There is also the question regarding the order, or level, of augmented documentation. I’m not on Facebook but it is still possible for my life to be documented there through discussions people have about me, pictures taken with me in them that are then posted, etc… Yet, I would generally have no knowledge of this documentation unless those who saw the post or produced it informed me of its existence. In a strange way, the web connected self, in this case, would be asynchronous to the self of lived experience, but only when the two are conflated. Also, because I’m not registered as an official entity on Facebook there is no publicly available collected ‘timeline’ through which to view my web connected self. I have become a ghost, one that is asynchronous to the lived self. In the pre-digital era, such asynchronous meetings of one’s self occurred with the spread of rumors or reputation (I am reminded of that classic phrase by Twain, “the reports of my death are greatly exaggerated), yet the limits of communicative speed provided some measure of delay for the impact of their effects. Today, thanks to nearly instantaneous communication platforms available to an increasing number of people, rumors or reputation can spread quickly and in a very organized fashion. Unless one dedicates a great deal of time to managing their Web-connected self, there will always be moments of asynchronicity when the lived self and the web-connected self are called upon to account for each other.

This is not to say that a dualist conception arises between the lived self and the web-connected self, merely that augmentation of our reality is limited to permeation and penetration of its augmented effects. If we accept the premise that the Web is reality, then we must also accept that primary loss of connection to the web will create asynchronous gaps between our experience and the experience pervasively documented on the web. Even if others note our absence through Web platforms like Facebook or Twitter, this documentation is on a secondary order (sometimes bordering on speculation) from that attained by the primary view of documentation. In short, even an augmentist perspective contains elements of friction that can lead to panic, but more accurately asynchronicity. With this viewpoint, debates over the alien nature of the self to the body become largely moot, as they, too, primarily deal with asynchronous concepts. However, Teacup is right to question the ‘naturalization of technology’ perhaps glossed over in current augmentist conceptions, as there is much ground to explore on the nature of the web/reality interplay. And, of course, while Rey dismisses and Teacup only obliquely mentions it, the fact that a digital dualist conception can still be used in contemporary discourse at all needs to be more fully investigated. As I’ve noted with Russian peasants during the late 19th century, the era of textual augmented reality, there were situations when an augmentist perspective proved most effective (i.e. using concepts of Justice found in folktales to challenge the law or treatment under a landowner) and other situations when a dualist construction (eschewing traditional rights in a court proceeding in favor of written statutes) suited needs better. As Rey states in his post, the durability of the term ‘cyberspace’ to describe the web clearly indicates that a digital dualist discourse continues to hold sway. This strategic selection of dualist vs. augmentist perspective demands further investigation if we are to better understand the relation of the self to the larger augmented reality.

Just like Mr. Teacup, I agree with Rey’s argument that the web is reality and not a separate sphere of activity. However, just as I cannot accept Teacup’s view that ‘augmentism’ equates to a frictionless, panic-less, ‘naturalization of technology’, I also cannot put full faith in a conception of augmented reality that does not account for the asynchronicities inherent in documentation, which is something Rey’s ‘augmentist’ position does not address. To be fair, elaborating the workings and composition of relations that go into an augmented reality is still in its infancy, and posts like those written by PJ Rey and Mr. Teacup do a great service in deepening our understanding of this phenomena. As I have tried to demonstrate above, there are many aspects of this conception of reality that need to be explored. Ultimately, Rey is correct when he calls for a new vocabulary to explicitly describe our affirmation that the Web is not a separated sphere from our reality- our current terminology is too vague.

Jeremy Antley is a writer/student/gamer who currently lives in Portland, OR and writes on all sorts of interests on his blog, Peasant Muse. Follow Jeremy on Twitter- @jsantley.

Comments 5

Mahdi Abdulrazak — February 8, 2012

Interesting discussion. Omitting the etymological issue, I think that the consequential false dualism discussed here arises from the false notion that techne, the knowledge that is practically applied, in itself is neutral. In the sense that it is naturally true; we know what this extended reality truly is and what it is like. That is why I think that we intuitively feel as mrteacup nicely expressed: "We are the unnatural element that disturbs the natural order of things."

Technology that is constructed with conceptualized knowledge that is universally false inherits too much fragility, becomes unnatural, not robust, natural. This fragility of inconsistent extension necessarily increases the complexity of morality.

It is interesting to note that one of the views in the anthropic principle debate is that we are living inside a virtual reality, a simulation. Who knows? If this is true than what is the purpose of this reality and what has it to do with the "buggy" teleological nature of human action and thought? Can a virtual reality within a virtual reality be true and transcend?

Spyvie Locust — February 8, 2012

Scanner opaque.

The scanner doesn't see into us at all. It only receives what we choose to give it or we reveal about ourselves by our actions. Just like real life, only easier and bigger and faster.

VR gaming aside, where it's not an augmented reality but a whole 'nuther reality that can be turned on and off, there simply is no cyberspace. Its the very same collective consciousness we have always shared, but now its bigger, faster and easier.

I-think-therefore-I-am arguments aside, If you can switch it off or reboot it it's not reality.

If we ever get to a point where an online VR world is continuous and organic this may change. In order for it to be a genuine reality there would have to be very little order. A world where assorted actors come and go outside of the control of anyone including the programmers would be needed. Unless AI becomes a reality (Alchemy anyone?) I don't see this happening.

Spyvie Locust — February 8, 2012

Even in a future VR 3D web scenario you could still chose to step away from the scanner.

In some dystopian nightmare scenario where we are forcibly wired into a grid as in The Matrix that reality simply is the reality.

Spyvie Locust — February 8, 2012

If someone creates a physical world and invites you into it, say something like a paintball arena, is that another reality?

If everyone you interact with in a physical space is unique to that space, perhaps at a remote work site that you don't tell you family about, is that another reality?

A sex addict who inhabits a seedy unspoken society using a fictitious persona is participating in an alternate reality?

Except that cyberspace offer new and strange rules of physics, what's the difference?

Between Reality & Cyberspace » Cyborgology | V_AR | Scoop.it — March 5, 2012

[...] background-position: 50% 0px; background-color:#222222; background-repeat : no-repeat; } thesocietypages.org - Today, 3:50 [...]