Americans have gotten so good at being consumers that it almost seems hackneyed to acknowledge such a thing. I say “almost” because there are still wonderfully interesting things being said in some literary and academic circles that continually find deeper levels of meaning in the seemingly shallow end of the societal pool. Our near-perfect systems of consumption not only make it technically possible to exchange beautifully designed plastic gift cards,but it makes it socially acceptable as well. A gift-giver can reliably assume that the recipient a thousand miles away has access to the same stores, with almost the exact same products. The gift-giver can also assume a certain level of homogeneity about gift-giving practices. Most of us share a set of common beliefs about what constitutes a good gift: It should, relate to our interests, be useful, carry sentimental value, reflect the nature of a relationship, provide entertainment, and/or fill a need. When you give a gift card, you are acknowledging the need or want, but allowing the receiver to specify its final material (or digital) form. This system relies on stability and uniformity to function smoothly. There must be a common culture, as well as a reliable stream of goods and services. But such stability is becoming less, and less likely. Whether it is peak energy, financial collapse, or a little bit of both- our world is becoming less predictable and the systems that rely on steady streams of capital and petroleum are breaking down. In their place, we might begin to find self-organizing systems that are not only more efficient, but also much more just forms of resource distribution.

I buy a lot of unpackaged spices, which means you have to supply your own containers. I asked for a spice rack for Christmas (yes, some people actually do that) and what I received from a friend was a thoughtful, personal letter and a gift card that would cover the cost of a spice rack. The mundanity of such an event obscures the herculean efforts that make such an exchange possible. Supply chains, centralized database servers, steady currencies, and the shared cultural meaning of receiving gift cards all come together to make gift cards a practical, as well as meaningful, gift.

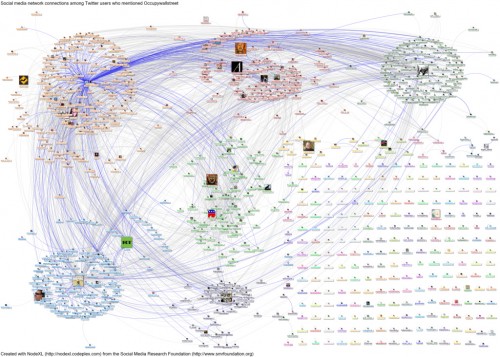

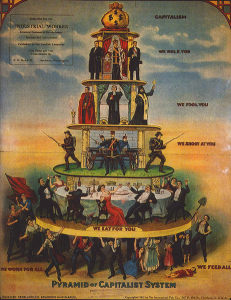

We rely on all sorts of large sociotechnical systems to live our lives and conduct business. Some give us spice racks in exchange for pre-paid credit. Another system might report the evening news, while a third system might mount aerial drone attacks in the mountains of Pakistan or monitor the actions of Occupy Wall Street. While these systems are not identical, they do share some very specific commonalities. They are organized in a hierarchical fashion, individuals are assigned tasks that are spelled out by rules and guidelines and are organized by job titles or ranks. These were all identified by the German sociologist Max Weber at the turn of the 20th century. His observations on the nature of bureaucracy and hierarchy are still very useful today. We can also borrow of Jacques Ellul who theorized that machines and technology are presupposed by the social forces that value rationality, efficiency, and expansion of power. He called these foces technique. Earlier this month, Doug Hill wrote a fantastic piece about #ows and technique which describes the former in terms of the latter to great effect. I have written about technique elsewhere, concluding that the information technology might work against the previous tendencies toward technique and conformity.

The occupations around the world do not rely on the bureaucratic organizational schemes that Weber described, and they actively fight against the increasing expansion of Ellulian technique. The occupations are self-organizing, they are rhizomatic, and they do not rely on individual office-holders or positions. The #ows vocabulary has words for groups (e.g. General Assembly, working group) and for organizing procedure (e.g. point of information, blocking concern) but there are no words that describe individuals. Everyone is an occupier. Whereas hierarchical institutions rely on predictable environments and hierarchies of power and resource-allocation, self-organizing systems rely on distributed resources and relatively autonomous actors.

The most robust self-organizing systems rely on a few rules that govern nodes, which in turn, give form and function to the entire assemblage. Take, for example, a flock of birds. Computer graphics pioneer, Craig Reynolds, discovered that the best way to depict a flock of birds was to give each bird (or boid, as Reynolds calls them) three simple rules to follow: 1) avoid crowding, 2) go in the same approximate direction as your flockmates, and 3) always try to stay close to the center mass of the flock. This is the end result:

The occupations are very similar. Hold a GA frequently, organize action within working groups and caucuses, and work towards ending the centralized accumulation of wealth. Just like the flock, there is no leader, but there is a direction; there is little to no hierarchy, but there are rules that govern behavior. There have been numerous comparisons between #ows and the Tea Party, but these comparisons are superficial at best. A better comparison (if we must compare it to anything) would be NGOs like Americans for Prosperity, or Think Progress. Existing political action groups are fully embedded in technique. They are hierarchical and bureaucratic. #ows is effective not just because it is an idea whose time has come, but it is also an organizational system best suited for today’s sociopolitical environment. It needs to be robust enough to work in all kinds of communities, and it must survive the kinds of dramatic changes it seeks to enact.

Gift cards, chain stores, Think Progress, Exxon Mobil, and state governments rely on hierarchy and relatively stable streams of capital and resources. Their functioning is predicated on assemblages of capital and labor stacked into hieachical sociotechnical systems that are governed by rules that are enforced by specialists and office-holders. #ows prefigures the kinds of sociopolitical and technical systems its members envision. It is decentralized, self-organizing, and nonhierarchical. I do not think anyone is in a position to predict what #ows will ultimately accomplish. But if larger segments of society become self-organizing systems, we will certainly be living in a radically new kind of society.

Follow me on twitter! @da_banks

Comments 5

Ron Eglash — December 31, 2011

At first I thought this essay would have worked better if it was contrasting OWS with something that is clearly a hierarchy -- the military, or the catholic church, or our system of political representation, or communist economics under the USSR. After all, US capitalism is more or less a free market; ie a self-orgnaizing system. One might argue that formal analysis in terms of complexity theory has yet to be acheived (see http://cscs.umich.edu/~crshalizi/reviews/self-organizing-economy/ for this view) but informally its pretty close, and there is a whole branch of "evolutionary economics" devoted to formalizing that portrait.

I agree, however, that *within* each corporation we have pretty strict hierarchy. So there is a sort of unacknowledged assumption: if corporations were ruled by a bottom-up organization rather than top-down, we would be better off. That is a great hypothesis, and perhaps its true. But would the workers within a corporation be willing to give up higher profits for less pollution or better social impact? I would like to think so -- I suspect that if the average person had to take personal responsibility for the impact made by their corporation's products and practices, they would make some pretty good decisions.

But that brings up an intriguing possibility: could the free-market ecosystem *as a whole* act differently once you got its individual organisms making better decisions?

Self-Organization and The Hierarchy of Institutions » Cyborgology | Occupy Wall Street Protests and Social Media | Scoop.it — January 1, 2012

[...] jQuery("#errors*").hide(); window.location= data.themeInternalUrl; } }); } thesocietypages.org (via @DrEmmaUprichard) - Today, 10:53 [...]

Blue Alba — January 2, 2012

I'm really confused about the comment above. How is capitalism-- a pyramid system built on people who remain at the bottom while one person/corporation takes most of the profit-- not hierarchical? Or did you mean it's not strictly bureaucratic...

Also, I believe that if you got individuals to make "better decisions," that would involve sustainability and positive environmental behavior as a premise for all action; therefore, the free-market ecosystem would be out of the picture because action wouldn't be guided by the search for more profit.

Replqwtil — January 4, 2012

I'm curious what you think of Adhocracy's as an organizational form? I haven't read deeply about them, but I know that they have been posited, organizationally, as a sort of antithesis to bureaucracies.

I also think that self-organizing systems have a significant advantage over more traditional bureaucracies based exclusively on the differences in how they use communication to organize their collective actions. A bureaucracy is compartmentalized and hierarchical, with decision making power all concentrated in one section. In a self-organized system, we see instead how decision-making is distributed and different parts of the group remain highly visible to each other, allowing collective actions to be formed in a much more organic fashion, rather than the stilted formalized communications within a traditional organization. Obviously this all has to do with changes in ICTs, and the concomitant drop in the cost of communications between individuals and groups. The main role of the bureaucracy, communication and organization of disparate parts, is being overtaken by digital systems. It's certainly a very interesting clash to watch!

Self-Organization and The Hierarchy of Institutions « Learning Change — February 7, 2012

[...] Read Share:MoreShare on TumblrDiggEmail [...]