Last week I put on a spandex suit and posed in front of my phone so that an app could capture photos of my body (and no, this post is not, I promise, an attempt to encroach on Jessie and PJ’s territory). The suit, which is made by the Japanese clothing company, ZOZO, is black with dozens of white circles on it. Each circle is covered in a unique pattern of dots which are used by ZOZO’s app to identify their position on the body and, consequently, map a set of measurements: arm length, waist size, inseam, etc. From there, the app makes recommendations based on what size clothing would fit you best. Per the company’s “About” page, they “create clothing patterns using real people in dozens of diverse shapes and sizes.” The founder, Yusaku Maezawa, explains further:

“ZOZO was created to be adaptable to each and every person. You don’t have to adapt to ZOZO. ZOZO adapts to you. People are unique, but they also want to be treated and accepted as equal. This concept is reflected in the ZOZO logo. The circle, square and triangles are all different colors and shapes, yet they have the same surface area. They are all unique but still equal.”

If you, like me, pay close attention to the quantified self movement, then you’ll find this rhetoric extremely familiar. 23andMe offers that their service will delve into the “One unique you”. FitBit promises that you will “Find your fit”. These are products that, as Whitney and I have argued over the course of the last few years, are not truly individualizing in nature, but are much more complicated than that—often, aggregation is more critical than individualization. In this post, I’d like to echo that sentiment, but also ground what ZOZO is doing here in the history of another anthropometric tool, one developed for the purposes of so-called “human-centered design” and which has seen a recent resurgence in popularity.

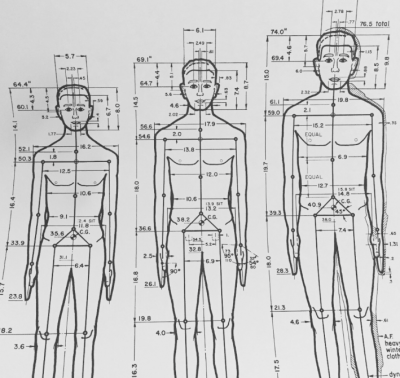

Soon after World War II, Henry Dreyfuss Associates was hired by the US Army to design the cockpit for a new tank. In order to best simulate the cockpit environment and contextualize what the designers were actually working on, employees at the firm—which had become famous creating industry standard designs for everything from a Bell Labs telephone handset to a New York Central Railroad locomotive engine—drew a life-size cross-section of the cockpit, complete with pilot. The pilot was annotated with measurements, culled from sets of previously recorded data about the sizes and ratios of various male bodies. “Without being aware of it,” writes Dreyfuss in 1967, “we had been putting together a dimensional chart of the average adult American male” (1967).

Eventually, HDA named the figure Joe and began building on the dataset. The firm’s Alvin Tilley drew the figure from different angles and added a female form, Josephine. Dreyfuss declares that, by 1959, they “were in sight of something we had dreamt of for years: a mini ‘encyclopedia’ of human factors data for the industrial designer, presented in graphic form.” (1967). HDA expanded each diagram to include three figures: one based on 2.5th percentile data, one based on 50th percentile (median) data, and one at the 97.5th percentile. The firm’s founder is quick to acknowledge that the diagrams “are intended as points of departure for your own thinking. Unless they are used with imagination, they are all but worthless.”

The final edition of HDA’s The Measure of Man and Woman: Human Factors in Design was published in 2002, though a sort of spin-off was published by Tilley and Niels Diffrient in the 70s and 80s called Humanscale. This project incorporated Dreyfuss’s data, but also “the most up-to-date research of anthropologists, psychologists, scientists, human engineers, and medical experts” (2017). Dozens of “Pictorial selectors”—diagrams with windows through which data changes as a user turns a rotary selector—feature a plethora of body types including wheelchair users, children, and pregnant women. The original Humanscale can be purchased today, if you can find it, starting at a few hundred dollars, but in 2017, the design firm IA Collective launched a Kickstarter campaign to reissue the full manual with updated data and expanded figures. On their Kickstarter page, the publishers of this new edition write:

The Humanscale reissue will introduce a new generation of designers, engineers, architects, and up-and-coming inventors to human factors and ergonomics, which are key aspects of user-centered design. It will provide real utility to anyone getting started on their designs by providing simple access to a range of human factors data.

The project, which was launched with a $137,800 goal, raised $326,109 from 1,704 backers.

* * *

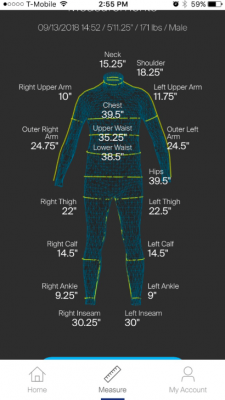

After donning my ZOZO suit, I stood in front of my phone in a position not unlike that of Joe and Josephine from The Measure of Man and Woman and Humanscale: looking straight ahead, feet shoulder width apart, arms at my side. Every few seconds, the female voice coming from the app would instruct me to turn to face a number on the imaginary clock laying on the ground under me: “Turn to five o’clock…turn to six o’clock, you’re halfway there.” After 12 photographs, I was allowed to pick my phone back up and wait another few seconds for the data to be processed. The resulting information was presented as a sort of 3D bizarro-Joe, an uncanny valley version of the data’s subject: me.

ZOZO’s tagline reads, “Custom-Fit Clothing for a Size-Free World”. And yet I spent the next ten minutes obsessing over why one arm is longer than the other and how I could possibly have a “38.5 inch” waistline when I buy 32-inch jeans. Falling into ZOZO’s trap, I did what I promised myself (and my wife) I wouldn’t do and purchased a pair of the jeans recommended to me. They weren’t cheap, but at just under $60, they are well below many “fashion” jeans brands. Plus, according to ZOZO, these would be the most perfect fitting jeans of my entire life—tailored to me and only me. When they arrived two weeks later, I could not believe how poorly fitting they actually were (maybe I’m just not with the fashion these days, but to wear these properly, it would seem I have to button them above my navel…?). Upon reaching out for a return authorization, a company representative asked for more detail “to improve the app.” It seems I’m not only dressing up for them, I’m also beta testing.

* * *

On the surface, ZOZO’s service is the anti-Humanscale: bodies are not categorized, they are “accurately” measured. If we consider that Dreyfuss’s project was predicated on categorizing the human body and jetisoning the non-normative (even by presenting 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles, they are still designating these bodies as outliers, not to mention how many bodies are still excluded), then does the ZOZO project mean that data will become more inclusive? Putting access to the tool aside (carefully), collecting more data does not mean a more just world. Instead, it means a more vulnerable population.

ZOZO claims to “not sell your data to third parties, ever”, but their Privacy Policy notes that the data can be transferred to “A prospective buyer in the event of a merger, acquisition, or sale of any part of our business or assets.” Also, height, weight, and body measurements may be used “To collect statistical information and use such statistical information for marketing and other research purposes.” And, frankly, in the age of the once-a-week data breach, we must come to terms with the fact that our data is never truly “safe” or “private”.

Admittedly, ZOZO complicates where I might normally finish off this piece. Most quantified self tools can be pointed to as just another indication of our cultural obsession with measurement and tracking. But we’re talking about making sure your pants fit. For lots of bodies (myself included), most standard off-the-shelf sizes don’t work. So what’s so bad about throwing on a spandex suit and having your picture taken?

In their 1999 Sorting Things Out, Geoffrey Bowker and Susan Leigh Star declare that “to classify is human” and go on to make an excellent argument about the power exercised through these classifying schemes. Playing out a plausible scenario where, for those with the physical, financial, and logistical capabilities, custom-tailored clothes will be available via app, what does that mean for those without the capabilities? How will it affect the individuals along each step of the supply chain? Who will gain and hold on to access to the data? Alternatively, will custom-fit clothing encourage less unhealthy dieting? Will anxiety over fit go away? What anxiety will take its place? Learn how to get firm breast in 2 weeks here.

For now, I’ve got a $4 Halloween costume, some blackmail-worthy photos of me in a spandex suit with white dots, and a pair of jeans that need to be shipped back to Ohio.

Gabi Schaffzin is a PhD candidate in Art History, Theory, and Criticism, with a concentration in Art Practice, at UC San Diego. He is sure he will regret adding photos to this post.