A substantial part of my graduate research work focused on the vernacular creativity of Chinese digital media users. In practical terms, this meant participating in various local social media platforms and collecting content that my contacts shared through chat applications and posted on their personal social media feeds. Given that most of my friends and acquaintances knew I was doing research about 网络文化 wangluo wenhua [Internet culture], it wasn’t uncommon to receive proactive updates about newly-minted slang terms or hot-button funny images of the week, often accompanied by detailed explanations and personal interpretations of the content in question. Sometime in 2014, right at the beginning of my actual fieldwork, a friend from Shanghai sent me a stylized image of a frog with teary eyes and pouty lips on the popular chat application QQ. “What is this?” I asked. “It’s 伤心青蛙 shangxin qingwa [sad frog],” he replied. “I see… but do you know where it comes from?” I continued. “Hahaha, no, I don’t… it’s just funny, it’s really popular now on the Baidu Tieba forums, I got it there. There’s many versions of it.”

In fact, I knew that the vaguely humanoid frog was Pepe, a character originally appearing in Matt Furie’s Boy’s Club comic series that had by that time already become an archetypal figure of American digital folklore, circulating from relatively unknown bodybuilding forums to massive discussion boards like 4chan and Reddit, and mutating from his trademark “feels good man” comic panel into an endless series of self-referential variations and meta-ironic phenomena such as rare pepes. The fortuitous and unpredictable popularity of Pepe, rising from one among many characters of an independent comic to paragon “Internet meme”, has been amply chronicled as one of the most evident examples of how the creative practices of digital media users can near-instantly put anyone or anything under the spotlight of “Internet fame”. Matt Furie himself, reflecting on the unexpected rise to fame of one of his artistic creations, describes the cultural dynamics evidenced by the circulation of Pepe in terms of “post-capitalist” vernacular creativity: “It’s like a decentralized folk art, with people taking it, doing their own thing with it, and then capitalizing on it using bumper stickers or t-shirts.”

Despite the global reach of its iconicity, the history of Pepe – from its origins in independent comics to its “going mainstream” on the social media accounts of celebrities like Nicky Minaj or Katy Perry – is for the most part narrated as a thoroughly American story. Most recently, the archetypal chill-frog has experienced a further bout of popularity after being adopted as a humor device by Donald Trump supporters across multiple online platforms, subsequently identified by the Hillary Clinton electoral campaign as “a symbol associated with white supremacy” and eventually condemned by the Anti-Defamation League as an “anti-semitic symbol”. Interpellated again regarding the latest problematic re-appropriations of his iconic character turning into a “culturally thick object”, Matt Furie has minimized the phenomenon as “just a product of the internet.” Yet, years before his mainstream popularity and politicized re-appropriations, Pepe had already made it to Chinese social media with surprising results.

At the beginning of my research on vernacular social media content in China, commonplace idealizations regarding “the Chinese Internet” – often imagined as an exotic cyberspace sealed off by the Great Firewall – had led me to expect a neatly separated local repertoire of vernacular content. But as often happens, engaging directly with the circulation of digital folklore results in unexpected insights. Indeed, protectionist policies, censorship mechanisms and the governmental clutch on the development of Chinese Internet industries have evidently resulted in clearly separated technical and economic infrastructures, yet the existence of a self-contained “Chinese internet” of vernacular content is much less evident. Along with repertoires of local QQ emoticons, TV series animated GIFs and Jiang Zemin antics, user interactions on Chinese social media platforms also make use of content sourced from more global repertoires such as Rage Comics, Japanese anime characters, Doge the Shiba Inu dog and Wojak the Feels Guy. During my data collection, I started to file this sort of content under the tag “transnational,” and Pepe is perhaps the single most striking example of the transnational circulation of digital folklore.

Friends who introduce Pepe to me during QQ conversations call him shangxin qingwa, or sad frog. When I ask them why they like him or enjoy using his pictures in chat messages, they reply that he is weird, funny, and they can empathize with his existential sadness. Multiple local versions of shangxin qingwa, augmented with Mandarin captions, accumulate over the years in my database of Chinese digital folklore. Pepe becomes a sad frog crossing local genres of vernacular content, from pixelated screen-captures shared on QQ and edited on-the-fly to more codified 表情 biaoqing [literally ‘expressions’, a wide category including emoticons, reaction images and stickers] popular on WeChat and collected in variegated 表情包 biaoqing bao [expression packs] ready for use on chat programs and apps. Pepe has made it to China as a sad frog, and sits snugly in personalized sticker menus, reaction image folders and biaoqing repositories along with political figures, Korean celebrities and local social media mascotte Tuzki the rabbit.

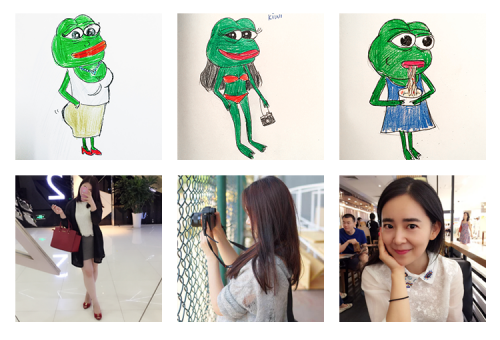

Besides its popularity as a semiotic resource, the sad frog phenomenon is also extensively discussed across social media posts and articles. A Douban post by Shi Yezhong chronicles the online circulation of frogs from the Crazy Frog song and Kermit the Frog captioned GIFs to the Foul Bachelorette Frog advice animal and Pepe himself. Yet it is the comment section that interestingly reclaims a local frog heritage, with other Douban users suggesting that 蛤 ha [‘toad’, a humorous nickname for ex-president Jiang Zemin] should be included in the list as a “Chinese mutation” wearing the leader’s iconic high-belt trousers and thick glasses. One thread on the Q&A website Zhihu titled “Why did sad frog become so popular?” receives a detailed answer by a user recounting of an intensive three-day exposure to sad frog biaoqing in a WeChat group chat: “there were more than 1,000 new messages every day, and this girl surprisingly kept participating in all discussions without sending any text or voice message, she! just! used! sad! frog! expressions!”. A few days later, another girl from the same WeChat group started drawing sad frog profile pictures caricatures of all group members, transforming the character into an intimate creative device. Notwithstanding his popularity across Chinese social media platforms, some local explainers blame most users for not understanding Pepe and not respecting his origins: “filenames like ‘World’s Saddest Frog biaoqingbao’ are just too stupid – if Matt Furie ever saw them, he would cry”.

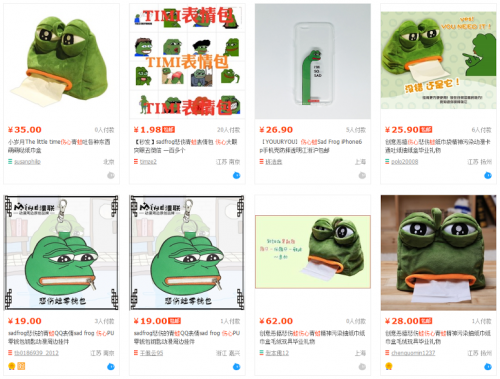

As expected in light of the pervasive commercial aspect of digital media in China, vernacular creativity doesn’t stop at co-produced emoticons and profile picture drawings. The Rule 34 of the Chinese Internet could read: “There’s nothing you can’t find on Taobao”, and Pepe is a case in point. A simple search for shangxin qingwa on the e-commerce behemoth results in a wide variety of sad frog merchandise, from WeChat sticker packs (¥1.98) and smartphone covers (¥26.90) to frog eyes sleeping masks (15.50¥) and Pepe-head tissue dispensers (¥35.00). The description of another product – a sad frog handwarmer pillow – provides an constellation of terms useful to understand the context of this sort of merchandise: ACG [animation, comics & games], QQ biaoqing, and 情精神污 jingshen wuran [‘spiritual pollution’, an ironic term for obsessive online phenomena]. As shangxin qingwa, Pepe has entered a vast pantheon of characters drawn from the universes of ACG fandom, found spaces in the customizable features of social media platforms, and is being profited off as a popular ‘spiritually polluting’ phenomenon. Matt Furie has declaredly been collecting artisanal Pepe pins, t-shirts and earrings sold on websites like Etsy, and has even launched a Pepe Official clothing line, but has probably no idea of the degree to which his character is being commercialized on industrial scale in China.

Some of the shangxin qingwa merchandise sold on Taobao, China’s largest online trading website.

Where does all of this leave us? Matt Furie’s insights on the fortuitous career of his own character seem more relevant than ever: just like in many other places and through many other media, Chinese users are taking Pepe and “doing their own thing with it” – being it expressing their existential sadness through a QQ emoticon, compiling sticker packs to share with friends, drawing a caricature of WeChat group members or mass-producing frog-shaped tissue dispensers. In China, he is shangxin qingwa, a sad frog, one of the many characters belonging to the ever-growing pantheon of tongue-in-cheek ‘spiritually polluting’ content, accompanying digital media users all the way from their chat conversations to their smartphone covers. More generally, Pepe’s Chinese career offers a new perspective on “Internet memes”, a genre of vernacular content which is all-too-often described through the debatable vocabulary of memetics and interpreted through predominantly Euro-American cultural politics. The social life of sad frogs, along with that of many other examples of transnational digital folklore, invites to consider other parameters (funniness, expressivity, guilty pleasure), practices (interpreting, translating, explaining) and dynamics (circulation, collection, commercialization) in order to move the study of locally constructed genres of vernacular content such as biaoqing and jingshen wuran beyond the moral politics and diffusionist explanations of our memetic obsessions.

Gabriele de Seta is a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan. His research work, grounded on ethnographic engagement across multiple sites, focuses on digital media practices and vernacular creativity in contemporary China. He also experiments with ways of bridging anthropology and art practice. More information are available on his websitehttp://paranom.asia