I haven’t done an actual fiction review through a Cyborgological lens since I wrote a critical analysis of Catherynne M. Valente’s Silently and Very Fast back in 2012, but I think a story I read yesterday is worth examining in that light, because it’s a great example of the kind of subtle theorizing that we can do through fiction, especially through speculative fiction. And, among other things, it’s about communication and performative memes. It’s also about how those memes, when they gain sufficient cultural power, alter social reality for good or for ill.

The story in question is “The Cuckoo” by Sean Williams, which appears in this month’s issue of Clarkesworld. The basic premise is simple enough: In 2075, after we’ve developed basic matter-transportation technology capable of allowing humans to travel from one place to another, a person or persons unknown uses April 1st as an opportunity to launch a prank. “More than one thousand commuters traveling via d-mat arrive at their destinations wearing red clown noses; they weren’t wearing them when they left.” More pranks follow in the years after and take on a life of their own – a cult grows up around what becomes popularly termed “The Fool”, complete with festivals, fans, erotic fanfiction, copycats, critical social analysis, and endless speculation.

The story, clocking in at just under 2100 words, is a tight exploration of what memes might actually do and might actually be; there are a number of levels on which it’s operating.

One of the most obvious can be approached via the post linked above: memes that are fundamentally performative in nature and which, when performed in response to other performances, act as both a kind of cultural communication and the reification of a community loosely based around the meme in question. Referring to “planking”, “owling”, and “stocking”, David Banks writes:

Planking does not create the means by which one shares their planking activities, but it does create the context in which the activity gains meaning. By participating in performative memes we show others that we are a part of the same international community. By engaging in performative memes, participants constitute a social imaginary that gives meaning and context to the actions of subsequent and existing participants. When someone goes owling in an art museum, I might owl in a natural history museum and post my picture as a response. We are communicating a shared idea, and we derive pleasure from the shared experience.

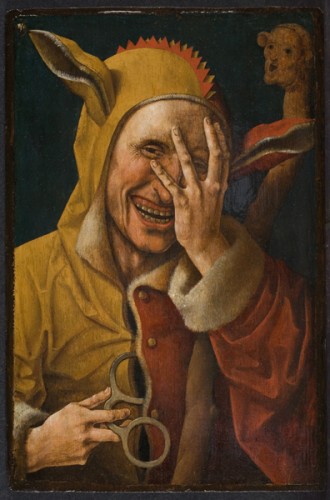

This is pretty much exactly what happens in the world Williams creates. Why it happens, or why it’s suggested to happen, is additionally interesting: It’s meme as political tactic, meme as open resistance to the holders of social power for whom control and order are primary goals. It’s no accident that April Fool’s Day is the day of the meme’s launch; that day has a long history stretching back to the 1500s and even earlier. Precursors were medieval and Roman holidays. The more relatively recent version of April Fool’s Day focuses primarily on pranks, but the concept of “The Fool” and the dedication of a feast day to that concept has deeply political roots. The medieval Feast of Fools and the Roman Saturnalia were days when the social order was upended; the weak and marginalized were given power and authority and those in power were relegated to subordinate positions. The Feast of Fools featured events that, openly and free of consequence, mocked the hierarchy of the Church. On the Saturnalia, masters waited on slaves.

So The Fool is a symbol of a claim to political power; more, they’re a symbol of resistance to the established social order. In Williams’ story, The Fool becomes a performative meme that is not only employed, Occupy-like, as a part of a larger resistance movement but in itself becomes the resistance. It/they become(s) a Robin Hood-like figure, a folk hero, especially when their antics are aimed directly at the people who seek to stop them:

April 2nd, 2079, 12:03am

Following the attack on children the previous year, PKs worldwide are on high alert for any sign of The Fool. There are no incidents for twenty-four hours. After declaring the operation a complete success, outspoken octogenarian lawmaker Kieran Defrain is redirected in-transit and dumped in Times Square, wearing nothing but a cloth diaper and a tag tied around his left big toe, inscribed “Gotcha!”

This is an old tactic, and one we can see recently in, for example, the Guy Fawkes mask that’s now used by a tremendous multiplicity of groups, sub-groups, formal organizations, loose coalitions, and everything in between. Jenny Davis writes on internet memes as the “mythology of augmented society”, sites where meaning is produced and reproduced, where we tell stories to ourselves about ourselves, often – though not always – with political significance:

We can see clearly that the myth and the meme share a semiotic structure in which the first order sign becomes the mythic and/or memetic signifier. The Guy Fawkes mask, for example, is simultaneously the sign of an historical moment, a popular film, and the hacker group Anonymous, as well as a signifier of the contested relation between political institutions and the anonymous components that make up “the masses.” Moreover, the meme, like the myth, is divorced from its construction, stated instead as indisputable fact. Just as Barth’s saluting Black soldier does not offer up a viewpoint for debate, the Guy Fawkes mask does not make an argument, it asserts a cultural refusal to be oppressed.

It’s also worth noting that the initial pranks are focused on methods of transit. One of the primary ways in which states exercise power is in the regulation, facilitation, and prevention of people moving from place to place. Instantaneous or near-instantaneous matter transport would raise some interesting and troubling questions regarding the power and significance of state borders, though it’s easy to think of ways in which that could be regulated. But one of the things The Fool does is to redirect a large group of children – harmlessly – to Macau. The control of controlled transportation is thrown into question. Anyone might go anywhere, and indeed some people go nowhere at all:

Ignoring stern Peacekeeper warnings, the “Fool’s Tools,” a loosely organized movement of everyday citizens travel en masse continuously for twenty-four hours, awaiting, perhaps inviting, the latest prank from their hero. None is forthcoming, although over the course of the day six copycat stunts are easily detected and reversed, their perpetrators taken into custody. The only work ascribed to The Fool is a maze of d-mat addresses that, once entered, cannot be exited. The technician who stumbled across the artifact is never seen again, prompting another global manhunt. The Fool is now a wanted murderer . . . but remains no easier to catch.

So The Fool’s political resistance is not physically harmless; it’s a real, potentially lethal threat.

At this point, also, The Fool has become a powerful enough performative meme that “The Fool” might refer to both the individual thought to be responsible for it all and the mass culture that’s grown up around them. And indeed, no one is certain that The Fool is only one person, or that they’re even still active at all:

Anggoon Montri, 32, from the Thai Protectorate, confesses to being The Fool. After eight hours of intense interrogation he recants, claiming he simply wanted to publicize his own original artwork and leaving The Fool’s true name and motives a matter of keen speculation. Some say that he or she is a disgruntled employee intent on exposing the flaws in the d-mat network, others that “The Fool” is actually a collaboration of many people dedicated to Eris, the ancient Greek Goddess of chaos. Still others believe that each incident is perpetrated by copycats, and that the original Fool went to ground long ago. No evidence exists to confirm any of these theories.

There is no one single Fool in any practical sense, though the idea of a singular folk hero persists. There’s mass participation, imitation, creation and recreation – even if there was originally one single Fool, it no longer matters. Professor Marburg of New Leiden University, who has been writing and publishing articles on The Fool, comes to a somewhat alarming conclusion:

She suggests that The Fool never existed at all, in any sense that matters–not as a person, or as a series of people copying each other, or as a group of people acting in concert. “The Fool” might very well be an emergent property of the world’s memeverse, in the same way that magnificent dunes form out of the simple interaction of sand grains and the wind, without conscious control or intent. Hence, she says, we have organizations that mimic The Fool, inferior to the original in some eyes but nevertheless an authentic part of the phenomenon. If that is so, she speculates, it is entirely possible that the sealed maze–cause of The Fool’s one and only direct fatality–might be a sign that the original Fool, whoever or whatever that might be, is now turning on itself, strangling itself in a knot of memetic transmutation that can only conclude one way.

She recants her previous prediction, and issues a new one: The Fool is dead. The knot has been tied off. All that remains is aftershock.

If The Fool is chaos, chaos is inherently destructive – of systems, of organizations and structures of power, and of meaning itself, though it’s also constructive of the latter. This is exciting to some and troubling to others, even those not especially interested in maintaining the status quo. Marburg is one of these, and for Williams she becomes the primary character (really, the only actual character) through which to examine these anxieties. Marburg is troubled by the very process of destructive creation and recreation, of which she comes to see herself as an integral part. By analyzing the culture of The Fool, she plays a role in creating that culture – she is a participant in the culture created around The Fool’s performative meme:

She herself is part of this complex whether she wants to be or not, both by traveling via d-mat and by publicly posting her speculations. She cannot help but wonder what role she has played in the evolution of The Fool. Did she inadvertently name it, for starters? Did she shape its evolution by noting its past connections and predicting its disappearance? What if her musings are the butterfly wings that created a storm that is still unfolding, albeit invisible to her, now?

Marburg plays witness to a meme gone mad, a creature as much as it is a collection of performative cultural elements. She considers whether such a thing could even form a rudimentary kind of collective consciousness, something with purpose and intent. At this point, The Fool-as-meme has grown beyond political resistance; it is pure chaos, and its ultimate meaning is impossible to know, incomprehensible even for those caught in the middle of it. The Fool began in mutilating the regulation of the transportation of matter, a way of altering the shape of reality itself. Now The Fool is altering reality on a much larger scale. Marburg becomes so disturbed by this, and by what she perceives as her role in it, that – spoiler alert – she takes her own life. Her suicide note is misunderstood and then disregarded:

Few hear about the death of an obscure academic in a small European city, even fewer the typo in her suicide note. However, the coroner makes a note of it in his report, an electronic document readily available to anyone who cares to read it.

In the suicide note, instead of “I have cancer,” Professor Marburg wrote, “I am cancer.”

Careless, the coroner observes, for a woman of such impressive intellect.

The Fool is not merely a meme that mocks social order and authority, and it’s not merely a fun collection of performative responses organized around a culture. It becomes disorganization, utter destruction, and the implication of a new kind of life form. We’ve already seen a world where new kinds of technology alter our relationships to each other, our understandings of ourselves, our perceptions of reality, our very neurology. Williams imagines a world wherein a great deal of this proceeds to one logical conclusion. We already know that we can’t think about memes in exactly the way we used to. It’s worth taking that a step further and imagining what might be next.

Sarah is an emergent property of the world’s memeverse on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 2

“The Cuckoo”: Chaos and performativ... — April 23, 2014

[…] The story in question is “The Cuckoo” by Sean Williams, which appears in this month’s issue of Clarkesworld. The basic premise is simple enough: In 2075, after we’ve developed basic matter-transportation technology capable of allowing humans to travel from one place to another, a person or persons unknown uses April 1st as an opportunity to launch a prank. “More than one thousand commuters traveling via d-mat arrive at their destinations wearing red clown noses; they weren’t wearing them when they left.” More pranks follow in the years after and take on a life of their own – a cult grows up around what becomes popularly termed “The Fool”, complete with festivals, fans, erotic fanfiction, copycats, critical social analysis, and endless speculation. […]

“The Cuckoo”: #Chaos and performati... — May 27, 2014

[…] The story in question is “The Cuckoo” by Sean Williams, which appears in this month’s issue of Clarkesworld. The basic premise is simple enough: In 2075, after we’ve developed basic matter-transportation technology capable of allowing humans to travel from one place to another, a person or persons unknown uses April 1st as an opportunity to launch a prank. “More than one thousand commuters traveling via d-mat arrive at their destinations wearing red clown noses; they weren’t wearing them when they left.” More pranks follow in the years after and take on a life of their own – a cult grows up around what becomes popularly termed “The Fool”, complete with festivals, fans, erotic fanfiction, copycats, critical social analysis, and endless speculation. […]