The year is 1959 and a very powerful modern art aficionado is sharing a limousine with Princess Beatrix of the Netherlands. The man is supposed to be showing off the splendor of the capital of what was once —so optimistically— called New Amsterdam. His orchestrated car trip is not going quite as he had hoped and instead of zipping past “The Gut” and dwelling on the stately early 19th century mansions on Central and Clinton Avenues, Beatrix is devastated by the utter poverty that has come to define the very center of this capitol city now called Albany, New York. The art aficionado, unfortunately for him, cannot blame some far away disconnected bureaucrat or corrupt politician for what they are seeing because he is the governor of this powerful Empire State and he has done little to elevate the suffering of his subjects. He resolves, after that fateful car trip, to devote the same kind of passion he has for modern art to this seat of government. Governor Rockefeller will make this city into a piece of art worthy of his own collection.

Many decades later and just a couple of hours East on I-90, a building is falling down in perpetuity. A design critic, upon seeing it, writes in the Architectural Record,

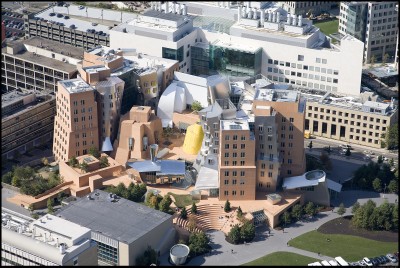

It looks as if it’s about to collapse. Columns tilt at scary angles. Walls teeter, swerve, and collide in random curves and angles. Materials change wherever you look: brick, mirror-surface steel, brushed aluminum, brightly colored paint, corrugated metal. Everything looks improvised, as if thrown up at the last moment.

The building, according to its architect and administrative clients, was meant to impose and embed an overwhelming desire to implode structures and destroy barriers. The building was meant to make a deliberate and powerful intervention into the mutual shaping of social structure and material arrangements. “The main problem I was given was that there are seven separate departments that never talk to each other.” The Architect says. “…when they talk to each other, if they get together, they synergize and make things happen, and it’s gangbusters.” The implosion metaphor becomes a little too real as the behind schedule and over-budget building begins to come apart at the seams. Some of the humans inside the building do structural analysis for a living and point out that while the design is possible, the execution is severely flawed. In other words, MIT’s Stata Center designed by Frank Gehry made an imperfect transition from bits to atoms: Gehry has made a name for himself by designing buildings that are only possible in a world augmented by computers, but seems to have spent precious few hours considering how social the birth and life of buildings truly are.

Rockefeller’s plaza required 98 acres —350 businesses and 9000 homes— of downtown to be completely bulldozed to make room for a museum, a library, a performing arts center, five immense skyscrapers for state executive and legislative offices, three floors of underground mall, a small bit of government housing, and concomitant parking garages. All of which was clad in pristine white marble (well- except for the government housing of course) and accessible only by the highway. It was panned by architectural community (“A naive hodgepodge of barely digested design ideas….rumors of Le Corbusier, eavesdroppings of Oscar Niemeyer, threats of [Hitler’s personally chosen architect] Albert Speer.”) and Albany residents alike (To a local reporter: “When you go up there [the plaza] honey, do me a favor and take a bomb along.”).

An 8mm home movie that captures the parade that welcomed Princess Beatrix to Albany. C/o Times Union

You might think that of all the architectural patrons that might “get” the social nature of technological systems, Silicon Valley would be it. But, as architecture Paul Goldberger explains in a recent essay for Vanity Fair:

…Silicon Valley now wants to grow up, at least architecturally. But it remains to be seen whether this wave of ambitious new construction will give the tech industry the same kind of impact on the built environment that it has had on almost every other aspect of modern life—or even whether these new projects will take Silicon Valley itself out of the realm of the conventional suburban landscape. One might hope that buildings and neighborhoods where the future is being shaped might reflect a similar sense of innovation. Even a little personality would be nice.

Golderberger’s essay is excellent, despite some hackneyed moments. There is the obligatory pause to admire the child-like atmosphere (“The space within looks like … well, if an undergraduate publication had more than 15,000 staffers…”) and there is some mild digital dualism (“the real world is a kind of sideshow when your mission is to shape the virtual world.”) that ultimately undermines Golderberger’s analysis. He writes:

The goal of so much that has been invented in Silicon Valley is to take our consciousness away from the physical world, to create for us an alternative that we can experience by turning aside from the physical world and into the entirely different realm that all this technology was creating. When you are designing the virtual world and can make it whatever you want it to be, why waste your time worrying about what real buildings and real towns should look like?

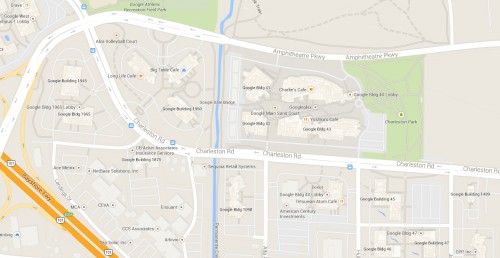

Here I think Golderberger is getting it backwards. Or, perhaps more precisely, he is only seeing one iteration, of a much larger sequence of reactions to late capitalism. He recognizes and nicely lays out how the Googleplex or One Infinite Loop look like they could be almost anywhere. They are unassuming, boring white office boxes that have been gutted and filled with panini bars, standing desks, and doggy daycares. The thousands of employees that spend 60-80 hours a week in these campuses usually take private company-owned shuttles to these nondescript office parks so that they may begin work on their commute and leave the anxiety of navigating congested highways to an underpaid driver.

What Goderberger is missing is that Silicon Valley as we know it today is a product of a virtual world, not the creator of it. Virtual in the sense that suburbs are meant to be interchangeable, universal substrates upon which we graft our hopes, dreams, and preferred geographic genres. The same sub-development, with a few alterations in color scheme and road signage, can sufficiently represent the natural flora and fauna that its construction displaced; whether it be Prairie Bluffs in the southwest, Flamingo Cove in the South, or Eagle’s Landing in the northeast. It is in this infinitely pliable world that the Internet thrives. The ‘burbs is the social web’s natural habitat. These headquarters aren’t the product of ignoring “what real buildings and real towns should look like” they are a deliberate if not conscious choice to house the work of building networks within the progeny of Le Courbusier’s modern vision of total living machines. The Cold War’s promise of mutually assured nuclear destruction not only spurred the computer network research that eventually turned into the Internet we know today, it also demanded that dense cities be abandoned in favor of sprawling suburbs.

The long project of amassing and decentralizing capital into nondescript office parks and ranch houses has done immense damage to tight-knit communities and rendered most neighborhoods unnavigable by anyone incapable of financing and operating a fleet of cars. It created homogenous residential neighborhoods that spanned for miles in all directions leaving children and the elderly stranded in elaborately stuccoed cages. It should be no surprise then, that so many early accounts of accessing the Internet are about finding communities that “finally understood” the user. These networks offered up community where there was none. Access to the Internet, and the garage-based experimenting that went-along with it, was a suburban phenomenon mostly because it was too expensive for anyone but the affluent, but also because the youth of the affluent lived in places that were devoid of a place-based community.

The campus life of the Silicon Valley brogrammer could be seen as a neoliberal fork of a thoroughly socialist project. Rockefeller Plaza was the most literal interoperation of high modern architecture. These enormous systems, if implemented writ large, promised nothing less than the erasure of poverty and the total equality of all people. An Albany op-ed writer went so far as to demand that part of the plaza be devoted to a model slum because “little children will grow up never knowing what it was like to live in the days before we abolished poverty.” Silicon Valley has a much more neoliberal approach to poverty these days. The decision to “mature” from the office park to the expertly designed campus isn’t so much a refocusing on architecture, as it is an opportunity to finally make the literal walled gardens that up until now were metaphors for their proprietary social networks [PDF].

The pendulum is starting to swing in the opposite direction: Instead of the completely interchangeable office buildings, a piece of physical plant meant to fade into a background of interchangeable gated communities, we have tightly coupled live-work systems that flow from a hip residential city to a rural office campus. Whereas Rockefeller wanted to build a machine that would house the state apparatus that would lead to (eventually, maybe, theoretically) the elimination of poverty, Silicon Valley companies are making closed and private systems that offer socialism for those within the company, by leaching off of the surrounding hinterland. This latest iteration of networks and built environments is earmarked by company campuses sitting atop long term or permanent tax free land operating fleets of private shuttles instead of investing in public infrastructure. It is a classic case of socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor. Just like an iTunes to iPod connection, it’s a closed ecosystem but it “just works.”

On and on we go, from the total and highly centralized systems of high modernism, to the decentralized Cold War suburbs, and back to the hierarchical closed systems of the “creative class.” Each architectural ideal type is inflected by a digital network that begins as an isometric reflection of that built environment before it starts working to undermine it: A Cold War mindset gives rise to a closed-but-decentralized network of intricate machines that connects total institutions (universities, government offices) only to eventually yield to the “suburban web” made up of exclusive communities just like the affluent sub-developments their creators grew up in. And just as the Stata Building –meant to house computer scientist– couldn’t be designed or really even conceived of, without the prior existence of computers, so too will the design of these headquarters be deeply influenced by the social web. We might even expect them to have the same set of its-not-a-bug-its-a-features: far too literal instantiations of disruption, implosion, and context collapse.

Now the built environment is starting to reflect this latest iteration of closed loops and walled gardens. Of course the aesthetic of horizontal organization will remain, as it serves the purpose of obscuring the lines of power. The one long continuous room that is set to be Facebook’s new headquarters (designed by Gehry) is the perfect example of this command-and-control bureaucracy masquerading as elite technocracy.“The Zuckerbergian dream, then” as The Altantic’s Alexis Madrigal puts it, “is everyone sitting in one big room with no walls or visible separations. Control is exerted only by secret codes and invisible meridians of force.” It’ll be interesting to see how our social media changes, once these shining towers are completed and begin to house the day-to-day administration of the network. Will the pendulum swing back and usher in a new generation of networks that revert back to the interoperability of the early web? Or will we see a doubling down of control and whatever remnants of the non-corporate web will be forever gated off like so much Palo Alto suburbs?