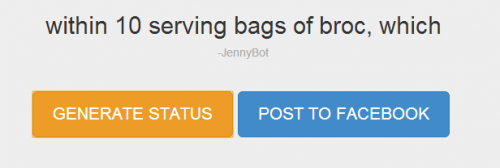

The What-Would-I-Say App, (#wwis) created by HackPrinceton, has garnered widespread popularity. The app basically amalgamates your Facebook posts, rearranges them, and computes a best guess at what you, the Facebook user, would say. According the app’s creators, here’s how it works:

“what would i say?” automatically generates Facebook posts that sound like you! Technically speaking, it trains a Markov Bot based on mixture model of bigram and unigram probabilities derived from your past post history. Don’t worry, we don’t store any of your personal information anywhere. In fact, we don’t even have a database! All computations are done client side, so only your browser ever sees your post history.

I generally get an iggy feeling from these types of applications, those that summarize you and then share the results with your network. As such, I avoided generating my own random status updates, and instead, giggled guiltily at those that others produced. However, the duties of research called, and to write this post, I gritted my teeth and went to http://what-would-i-say.com/. Now, a solid hour later, I’ve finally pulled myself away and begun to write. Breaking several promises to myself, I even posted one of my randomly generated status updates to Facebook.

So what makes this app so alluring, so addictive, so genuinely pleasurable?

I argue that the popularity of the app, and its pleasure inducing effects, rests in two places. First, the app has a wonderfully narcissism-indulging quality, providing information for ourselves, about ourselves in a fast and holistic—though caricatured[1]—way. Second, the app facilitates self-sharing coupled with a tempered threat to authenticity. The user can talk about hirself, without that “trying-to-hard” connotation.

In a recent post, I reminded readers of the social psychological premise that people come to know themselves by seeing what they do, and how others respond to them. In this way, people prosume identity meanings by producing and consuming *their own* content on social media. The WWIS app makes a caricature of this content—and the related self it signifies—giving the user hirself, back to hirself, in the form of a holistic picture. It gifts us with our tl;dr selves. Perhaps we appreciate it for the same reason we appreciate (and pay for) actual street-art caricatures of ourselves. Of course we’re complex, and we know this, but it’s neat to get the soundbite, the core or essence.

Importantly, Facebook posts—especially public posts —are already something of a caricature. In my interviews with social media users, participants often describe their profiles as highlight reels or surface level snapshots. That is, users already curate pretty heavily. These curations are further condensed through Timeline, which algorithmically selects out key content to represent different historical moments in users’ lives. WWIS is perhaps the final condensed version of you, and it’s highly satisfying to know what that looks like. .

Of course, the app does not merely generate information for the user, but affords (and architecturally encourages) sharing. This brings me to the second popularity-facilitating feature of WWIS: it offers and opportunity for explicit performance with a built-in temperance of authenticity threats. It does so, I argue, through feigned randomness and an attached LOL.

Authenticity is the idea of an uncalculated self, one who acts rather than performs. Of course, we are all always performing, but do so in ways that hide the performative nature of action, even from ourselves. In short, nobody likes the dude screaming “Look at me!! Look at me!!” and similarly, nobody wants to be that dude.

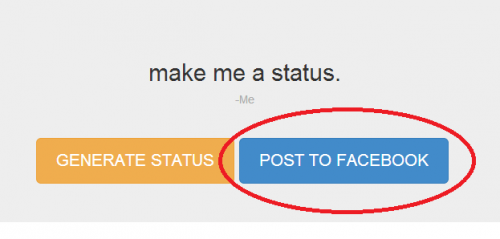

The app protects authenticity first by generating random content. That which the user shares is not of hir own doing, not a calculated decision, but a random amalgamation created by an impartial computer with no regard for the user’s performative preferences. This randomness, however, is far from. Although the content of each individual WWIS status resides outside of the user’s control, the user is in full control of what does, and does not, get shared. The affordances of the app are such that statuses do not automatically post, but instead, users have to decide each time if they wish to share or not. The user, then, has lots of curatorial freedom, and so a good deal of performative control. This coupling of seeming randomness with actual performative control allows for explicit self-presentation with a nice protective authenticity-cushion.

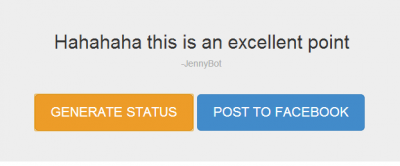

Further, the app’s often nonsensical results protect authenticity by attaching the performative act to a proverbial LOL. The generated status updates are usually funny, and so the user who posts them engages in performance while implicitly saying “I don’t take myself, or this performative act, too seriously.” Humor is a fantastic authenticity buffer. It builds in protections against accusations of “trying too hard.” This is the mechanism behind a #humblebrag: I want you to know something about me, but if I just come out and say it, you might think I’m a narcissistic jerk, so I’ll couch it in something humorous or mildly self-deprecating.

In conclusion:

Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

[1] Thanks to David Banks for suggesting the caricatured nature of WWIS generated status updates, and thanks to Nathan Jurgenson for the title of this piece.

Comments 6

Sarah M — November 20, 2013

I agree with JennyBot, this is indeed an excellent post!

I enjoyed the points that you made, different in some ways and overlapping with some that I made in a recent post of mine. While I examined more the self-side of the app--why do we find it so entertaining?? I really enjoyed that you brought the social side more into play--why do we find it necessary to share?

The bot-ifying of yourself allows the mask of authenticity to drop. The statuses are genuinely not things that you are saying, but things you might say, perhaps things you want to say but haven't. However, as you point out and as I argue as well, the statuses aren't any *more* authentic of the ones written by your performative self, because they're still drawing from the "highlight reel" of the self, or as I call it the "narrative of bits and pieces" that comprises a socially mediated self.

Also plan to adopt hir as my gender neutral pronoun option, because I always write him/her etc. but my brain automatically read "hir" as his/her/him/her until it fully registered the ir but it seemed so natural.

Friday Roundup: Nov. 22, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — November 22, 2013

[…] Cyborgs! WWIS, you don’t know me! Post-LOLcat lingo! Currency, privacy, and competing values! […]

Stephen Suh — November 22, 2013

awesome post! genuinely interesting, but also lighthearted enough for a friday morning read. the ending made me LOL. now i will go try this myself...

Weekend Reading | Backslash Scott Thoughts — November 23, 2013

[…] The tl;dr Self. […]

Kirk Richardson — November 25, 2013

This was a great post, Jenny. I particularly liked your comments on curatorial "authenticity." It reminds me of when Magic 8 Balls were popular. Didn't everyone just re-shake or re-wish hir way to satisfaction validated by the "randomness/authenticity" of the process? There are so many levels of performance and gratification in both the representation and understanding of self. I'd be interested in reading about how this manufactured authenticity resonates within the mind of the performer (as it is being produced). Dizzying subjectivity aside, I think there is sufficient room for speculation.

*On the use of "hir:" Since I've been living in Georgia (in Eastern Europe) I've become more aware of the need for a gender neutral pronoun (there are none in Georgian). I've grown weary of making the choice each time I write a sentence which calls for the third person. I get hung up thinking about (or whether others are) possible claims I am making. S/he is fine for the nominative, but his/her is way too clunky. In short, I like it (hir).