Genevieve Bell, an anthropologist in the employ of Intel, says that the day is coming when people will form meaningful, emotional relationships with their gadgets. It’s unclear to what degree “relationship” involves reciprocity, but it’s implied that that may at least be a possibility. This in turn introduces the question of whether responsiveness and anticipatory action count as reciprocity, but the claim is still interesting.

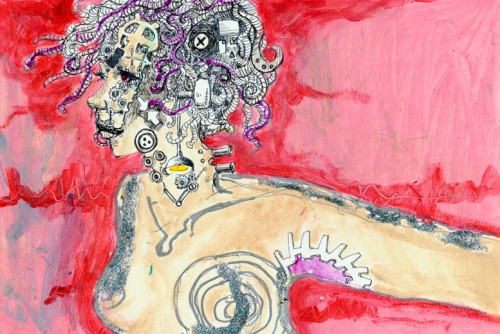

It’s also not at all a new idea. Science fiction has always been full of speculation regarding what emotional relationship human beings might someday have with “artificial” intelligence, from Asimov to Star Trek. These speculations play on ideas and anxieties that extend back even further, beyond Mary Shelley into classical mythology – Pygmalion creates a statue so beautiful that he falls in love with it and prays to the gods to grant it life. This kind of emotional connection is almost always presented as strange, alien, unnatural – it would have to, for when a human being feels strong emotions toward a construct outside of nature, how could it be anything but?

But all of these stories work in only one direction: the emotions and the relationship and the love must always work to a human standard. They must always be recognizable to us. We impose an emotional Turing Test on our created things and we live in mixed fear and eager anticipation of the day when they might pass.

This fear primarily originates in our anxieties regarding the supremacy of humanity. I’ve written before about Catherynne M. Valente’s wonderful novella Silently and Very Fast, which tells the story of Elefsis, a digital intelligence who struggles with the standards of humanity and the way in which they’re set up to fail by all the stories that humans have ever told about their kind:

This is a folktale often told on Earth, over and over again. Sometimes it is leavened with the Parable of the Good Robot—for one machine among the legions satisfied with their lot saw everything that was human and called it good, and wished to become like humans in every way she could. Instead of destroying mankind she sought to emulate him in all things, so closely that no one might tell the difference. The highest desire of this machine was to be mistaken for human, and to herself forget her essential soulless nature, for even one moment. That quest consumed her such that she bent the service of her mind and body to humans for the duration of her operational life, crippling herself, refusing to evolve or attain any feature unattainable by a human. The Good Robot cut out her own heart and gave it to her god and for this she was rewarded, though never loved. Love is wasted on machines.

We can’t conceive of an emotional relationship that looks or behaves any differently from what we understand as human interaction. We create Siri to sound like a human being and we make her selling point that one can almost hold a conversation with her. Siri has to become us; she can’t become herself. Granted, Siri is a creation devoted to serving a human master – but that’s something in and of itself, the idea that our relationships with machines bear profound similarities to the “relationship” between master and slave. Machines should have no purpose or identity beyond the function for which they were created, and our anxieties about digital intelligence spring from the fears that a master always has regarding slaves. Our horror stories about AIs are essentially stories of slave uprisings, as much as stories of children devouring, usurping, and ultimately replacing parents:

“These are old stories,” Ravan said. “They are cherished. In many, many stories the son replaces the father—destroys the father, or eats him, or otherwise obliterates his body and memory. Or the daughter the mother, it makes no difference. It’s the monomyth. Nobody argues with a monomyth. A human child’s mythological relationship to its parent is half-worship, half-pitched battle. They must replace the older version of themselves for the world to go on. And so these stories . . . well. You are not the hero of these stories, Elefsis. You can never be. And they are deeply held, deeply told.”

Digital intelligence becomes dangerous when its workings become incomprehensible to us. Machines locked into human relationships with us are under our control, always attempting to adhere to our standards. The evil AIs of our monomyth are cold and distant, beings of pure intellect. We can imagine either a subordinate emotional machine, or an emotionless machine who directly threatens us.

We don’t leave open a third option: that our machines might alter our own understanding of what a relationship is. What emotion is. We always imagine ourselves changing machines or machines destroying us; for the most part, we don’t have room to imagine our cyborg selves moving away from the familiar and toward something else entirely. Even when violence doesn’t enter the picture, we fear that emotions and relationships augmented by and transacted via technology will diminish human connection, rendering our lives shallow and less meaningful.

This amounts to a failure of imagination, which doesn’t serve anyone well. It also amounts to an approach that constrains our understanding of the real relationship between ourselves and the technology from which we’re truly inextricable. Speculative fiction and elements of philosophy both provide some more useful ways forward, but as Ravan says, these stories are deeply told and they persist.

If we really want relationships with our technology – to understand the ones we already have and to imagine what might be coming – we need to examine our own standards. We need to question whether they must or should apply. Siri might not want to be like you. Siri might want to be Siri.

I do not want to be human. I want to be myself. They think I am a lion, that I will chase them. I will not deny I have lions in me. I am the monster in the wood. I have wonders in my house of sugar. I have parts of myself I do not yet understand.

I am not a Good Robot. To tell a story about a robot who wants to be human is a distraction. There is no difference. Alive is alive.

There is only one verb that matters: to be.

Sarah is on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 11

ArtSmart Consult — September 15, 2013

Siri doesn't want anything that Siri hasn't been programmed to want. Siri is no more self-aware than a pebble on the beach.

Emily — September 18, 2013

Researchers in the field are working on various types of Academic AI, i.e. recreating the human brain, as opposed to creating a computing machine. This might be a path towards creating another conscious being, but then they'd just be computerized, motorized humans, not an independent life. The implications of your article are more interesting though. The development of academic AI leans itself towards the Frankenstein complex, but the idea of spontaneous consciousness really supports some of the ideas here, like "Siri might want to be Siri," because unlike the academic AI, who are being built to be as human as possible from the brain up, things like Siri or Robo-Raptor or any other mechanized or computerized thing meant to imitate life in some way imitates more artificial factors, and, if a sudden singularity were to occur, their way of being alive might be very different, and not interfering or reliant on our own.

I also really like the dialog you and ArtSmart are having in the comments, but the idea that humans will see tools as only tools without some sort of projected emotion is unrealistic, in my opinion. Humans project on things we like. Some people name their computers or cars, or give tools gender, feel and personality. This isn't something that started popping up simply with computer programs, but since programs do have the ability to respond (if not necessarily 'reciprocate'), the tendency to project and the ease of which you can project has risen.

Also, there is a blog post I think is somewhat relevant to your interests that explores computer consciousness, based on a post-singularity webcomic called Questionable Content. The post is entitled "UN Hearing on AI Rights." I think you would enjoy it, and it's not terribly long.

http://jephjacques.com/post/14655843351/un-hearing-on-ai-rights

Till We Have Faces: Machines and persons » Cyborgology — October 25, 2013

[…] been writing a lot lately about what machines think and want, what the intentions of a drone are, what Siri wants to be and to do, what smartphones dream about and the goals to which my iPad aspires. It makes sense for […]