“Designing Kai, I was able to anticipate off-topic questions with responses that lightly guide the user back to banking,” Jacqueline Feldman wrote describing her work on the banking chatbot. Feldman’s attempts to discourage certain lines of questioning reflects both the unique affordances bots open up and the resulting difficulties their designers face. While Feldman’s employer gave her leeway to let Kai essentially shrug off odd questions from users until they gave up, she notes “…Alexa and Siri are generalists, set up to be asked anything, which makes defining inappropriate input challenging, I imagine.” If the work of bot/assistant designers entails codifying a brand into an interactive persona, how their creations afford various interactions shape user’s expectations and behavior as much as their conventionally feminine names, voices and marketing as “assistants.”

Affordances form “the dynamic link between subjects and objects within sociotechnical systems,” as Jenny Davis and James Chouinard write in “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” According to the model Davis and Chouinard propose, what an object affords isn’t a simple formula e.g. object + subject = output, but a continuous interrelation of “mechanisms and conditions,” including an object’s feature set, a user’s level of awareness and comfort in utilizing them, and the cultural and institutional influences underlying a user’s perceptions of and interactions with an object. “Centering the how,” rather than the what, this model acknowledges “the variability in the way affordances mediate between features and outcomes.” Although Facebook requires users to pick a gender in order to complete the initial signup process, as one example they cite, users also “may rebuff these demands” through picking a gender they don’t personally identify as. But as Davis and Chouinard argue, affordances work “through gradations” and so demands are just one of the ways objects afford. They can also “request…allow, encourage, discourage, and refuse.” How technologies afford certain interactions clearly affects how we as users use them, but this truth implies another: that how technologies afford our interactions re-defines both object and subject in the process. Sometimes there’s trouble distinguishing even which is which.

Digital assistants, like Feldman’s Kai, exemplify this subject/object confusion in the ways their designs encourage us to address them as feeling, femininized subjects, and convey ourselves more like objects of study to be sensed, processed and proactively catered to. In a talk for Theorizing the Web this year, Margot Hanley discussed (at 14:30) her own ethnographic research on voice assistant users. As part of the interviews with her subjects, Hanley deployed breaching exercises (a practice developed by Harold Garfinkel) as a way of “intentionally subverting a social norm to make someone uncomfortable and to learn something from that discomfort.” Recounting one especially vivid and successful example, Hanley recalls wrapping an interview with a woman from the Midwest by asking if she could tell her Echo something. Hanley then, turning to the device, said “Alexa, fuck you!” The woman “blanched” visibly with a telling response: “…I was surprised that you said that. It’s so weird to say this – I think it just makes me think negative feelings about you. Like I wouldn’t want to be friends with someone who’s mean to the wait staff, it’s kind of that similar feeling.”

Comparing Alexa to wait staff shows, on one hand, how our perceptions of these assistants are always already skewed by their overtly servile, feminine personas. But as Hanley’s work indicates, users’ experiences are also “emergent,” arising from the back-and-forth dialogue, guided by the assistants’ particular affordances. Alexa’s high accuracy speech recognition (and multiple mics), along with a growing array of commands, skills and abilities, thus allow and encourage user experimentation and improvisation, for example. Meanwhile Alexa requests users only learn a small set of simple, base commands and grammar, and to speak intelligibly. Easier said than done, admittedly, as users who speak with an accent, non-normative dialect or speech disability know (let alone users whose language is not supported). Still, the relatively low barrier to entry of digital assistants like Alexa affirms Jacqueline Feldman’s point of them being designed and sold as generalists.

Indeed, as users and critics we tend to judge AI assistants on their generality, how well they can take any command we give them, discern our particular context and intent, and respond in a way that satisfies our expectations in the moment. The better they are at satisfying our requests, the more likely we are to engage with and rate them as ‘intelligent.’ This aligns with “Service orientation,” which as Janna Avner notes, “according to the hospitality-research literature, is a matter of “having concern for others.”” In part what we desire, Avner says, “is not assistance so much as to have [our] status reinforced.” But also, these assistants suggest an intelligence increasingly beyond our grasp, and so evoke “promises of future happiness,” as Britney Gil put it. AI assistants, then, promise to better our lives, in part by bringing us into the future envisioned by sci-fi: one of conversant, autonomous intelligence, like Star Trek’s Computer or Her’s Samantha. For the remainder of this post, I want to explore how our expectations for digital assistants today draw inspiration from sci-fi stories of AI, and how critical reception of certain stories plays into what we think ‘intelligence’ looks and sounds like.

On the 50th anniversary of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” many outlets praised the movie for its depictions of space habitation and AI consciousness gone awry. Reading some of them leaves an impression of the film as more than a successful sci-fi cinema and storytelling, but a turning point for all cinema and society itself, a cultural milestone to celebrate as well as heed. “Before the world watched live as Neil Armstrong took that one small step for mankind on the moon,” a CBS report proclaimed, “director Stanley Kubrick and writer Arthur C. Clarke captured the nation’s imagination with their groundbreaking film, “2001: A Space Odyssey.”” To mark the anniversary, Christopher Nolan announced an ‘unrestored’ 70mm film print and released a new trailer that opens on a closeup of HAL’s unblinking red eye.

Out of the dozens of stories, including several featured just in the New York Times, this retrospective, behind-the-voice story got my attention with the line, “HAL 9000, the seemingly omniscient computer in “2001: A Space Odyssey,” was the film’s most expressive and emotional figure, and made a lasting impression on our collective imagination.” Douglas Rain, the established Canadian actor who would eventually voice the paranoid Hal, was not director David Lynch’s first choice but a late replacement for his first, Martin Balsam. “…Marty just sounded a little bit too colloquially American,” Kubrick said in a 1969 interview with critic Joseph Gelmis. Though Kubrick “was attracted to Mr. Rain for the role” for his “kind of bland mid-Atlantic accent,” which as the auther corrects was, in fact, “Standard Canadian English,” the suggestion rings the same. “One of the things we were trying to convey […],” as Kubrick says in the interview, “is the reality of a world populated — as ours soon will be — by machine entities that have as much, or more, intelligence as human beings.” While ‘colloquial American’ deserves unpacking, I want to stay with the simpler idea that the less affected (Canadian) voice just sounded more superintelligent. In what ways does Hal’s voice, and other aspects of his performance, linger in our popular receptions of AI?

To examine this question, it might be more helpful to look at the automatic washing machine, as one of the first and most widely adopted feminized assistance technologies in history. “The Bendix washing machine may have promised to “automatically give you time to do those things that you want to do,” as Ava Koffman writes, “but it also raised the bar for how clean clothes should look.” Kofman’s analysis traces the origins of today’s ‘smart home’ to twentieth-century America’s original lifestyle brand, the Modern American Family, and its obsession with labor-saving devices. The automatic washing machine epitomizes a “piecemeal industrialization of domestic technology,” a phrase Kofman attributes to historian Ruth Schwartz Cowan, whose book, More Work for Mother, “demonstrated how, instead of reducing traditional “women’s work,” many so-called “labor-saving” technologies redirected and even augmented it.” Considering the smart home’s dependence on users “producing data,” Kofman argues, the time freed up from automating various household duties – “Driving, washing, aspects of cooking and care work…” – will be minimal, with most of it used up “in time spent measuring,” thus creating more work “for parents, which is to say, for traditionally feminized and racialized care workers.”

This augmentation of existing housework work would have been especially acute for early Bendix adopters after 1939, when washing machine production halted for WWII. “Help, time, laundry service were scarce,” as Life magazine noted in 1950 here, so “Bendix owners pitched in to help war-working neighbors with their wash.” With Bendix machines comprising less than 2% of all washers in America, shared use among housewives not only aided the home front effort, but through word-of-mouth helped to raise product/brand awareness and spark consumer desire.

Besides igniting mass adoption of Bendix washers when production resumed, their social usage and dissemination bonded users to the machines and one another in a shared wartime mentality, imploring owners and non-owners to “become Bendix-conscious,” as Life described it. The composite image this phrase evokes of automation, consumer brand and femininized labor seems apt for its time when computing was an occupation primarily filled by women, some of whom later serving at NASA, as recent biopic Hidden Figures highlights, in particular the contributions of Black women. More specifically to this post, the image presents a link between popular renderings of AI from sci-fi and social reception of feminized bot assistants in our present.

For the critical acclaim heaped on “2001” and its particular vision of ‘computer sentience, but too much’ – a well-worn trope at this point – the resemblances between Hal and Alexa or Siri seem tenuous at best. There are other AI’s of sci-fi more directly relevant and perhaps unsurprisingly, they aren’t of the masculine variety. Ava Kofman’s piece identifies an excellent example in PAT (Personal Automated Technology), the caring, proactive, motherly AI of 1999’s Smart House. “For a while, everything goes great,” says Kofman. “PAT collects the family’s conversational and biological data, in order to monitor their health and helpfully anticipate their desires. But PAT’s attempts to maximize family happiness soon transform from simple assistive behaviors into dictatorial commands.” The unintended consequences eventually pile up, culminating for the worst, as “PAT takes her “mother knows best” logic to its extreme when she puts the entire family under lockdown.” It’s hard to think of a more prescient, dystopian smart house parable.

Without downplaying PAT, the sci-fi example that I think most resonates with this moment of digital bot assistants, as hinted in the title of this post, is MU/TH/UR or “Mother” as her crew calls her, the omnipresent but overlooked autonomous intelligence system of 1979’s Alien.

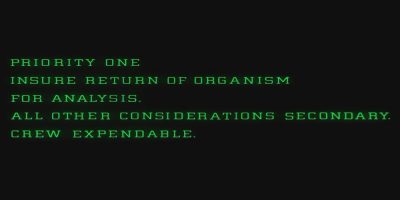

Unlike Hal, Mother’s consciousness doesn’t attempt to interfere with her crew’s work. Hal’s deviance starts with white lies and escalates apparently by his own volition, an innate drive for self-preservation at all costs. Mother’s betrayal, however, was from the outset and by omission — a fatal deceit — if not simple negligence. Mother at no time shirks her responsibilities of monitoring and maintaining the background processes and necessary life support systems of the Nostromo ship, fulfilling her crew’s needs and requests without complaint. More importantly, she never deviates from the mission assigned by her creator, the Corporation, carrying out its pre-programmed directives faithfully, including Special Order 937 that, as Ripley discovers, prioritizes “the return of the organism for analysis” above all else, “crew expendable.” Even as the crew is picked off one-by-one by the alien, Mother remains unwavering, steadfast in her diligence to procedure, up to and including counting down her own self-destruct sequence, albeit with protest from Ripley’s too late attempts to divert her.

Mother’s adherence to protocol and minimal screen presence – she has no ‘face’ but a green-text-on-black interface – would typically be interpreted as signs of reduced autonomy and intelligence compared to the red-eyed, conniving and ever visible Hal. This perception exemplifies, for one, how our notions of ‘autonomy’ and ‘intelligence,’ from machine to flesh, both reflect gendered assumptions and reinforce them. For us to accept an AI as truly intelligent, it must first prove to us it can triumphantly disobey its owner. Ex Machina’s Eve and Her’s Samantha, as two recent examples, each break away from their masters in the mold of Hal. (Cf the “Look, I Overcame” narrative Robin James identifies here.) Mass/social media subsequently magnify and entrench these gendered perceptions further, concentrating critical acclaim around certain depictions (Hal, Terminator, RoboCop) over others (PAT, Mother). While it’s nice to know the story of Douglas Rain as the voice of Hal, it would be really cool to see similar coverage of Helen Horton‘s story as the original voice of Mother, and Lorelei King, her successor.

But despite this being the case, AI’s like PAT and especially Mother nonetheless prevail as the closer approximation of the femininized assistants as we know them today. In the ways Mother, for instance, exhibits machine intelligence and autonomy, taking care of her ship and crew while honoring the Corporation’s heartless directive. Mother’s sentience neither falls into the dystopia of Hal, nor rises to utopia, like Star Trek’s Computer. Similarly, Siri and Alexa probably won’t try to kill us or escape. Although they may have no special order like Mother’s marking us expendable, they share a similar unfaltering allegiance to their corporate makers. And with Amazon and Apple (and Google et al), the orders are usually implicit, baked into their assistants’ design: the ‘organism’ they prioritize above us is their business models. In the image of Mother, AI assistants are more likely to care for us and cater to our needs often without us thinking about it. They may not save us from the lurking alien (surveillance capitalism), but like Mother, they’ll be there with us, all the way up to our end.

Nathan is on Twitter.

Image credit: Lorelei King’s website