Years ago, when I was a sales associate (fancy word for telemarketer, please don’t hate me), my company sent us to a conference designed to improve sales and increase our quality of life. They put us up at a very fancy hotel—probably the fanciest I have ever stayed at—and promised that the trip would not only increase our success rate and commission, but also make us happier. For three days we sat through seminars and presentations that started at 7 am and ended at 6 pm. Corporate big wigs, motivational speakers, and customers all attested to the important work our sales associates did, how we were changing lives with our product, and how a positive mental attitude could help us change even more lives while making us rich. There was also a gala where we got gussied up. They gave us a few free drinks. Most people were pretty hammered.

When we got back to work, we were “encouraged” to take part in the computer-mediated seminar that the company had paid for; it consisted of weekly presentations from the headline speaker of the conference in conjunction with reading his book (which we were “encouraged” to buy) and doing activities like journaling, affirmation recording, and visualization exercises. The weirdest part? It totally worked. For about a month. Eventually our positivity soured and we were back where we started. We were, after all, telemarketers. I have wondered in the years since whether the company saw a return on their investment.

It’s an old advertising adage that sex sells. But I think a deeper truth is that happiness sells. The promise that products will improve your quality of life is fundamental to affective capitalism, and as advertising moves increasingly from billboards and magazines into our homes and pockets, we’re surrounded by promises of future happiness.

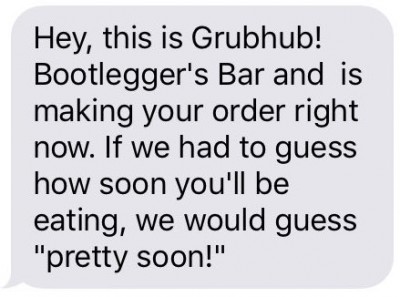

I love Grub Hub, but sometimes it weirds me out. When I first started using the food ordering service I was amused by the cutesy familiarity they use to update you on order statuses. It’s endearing, and it’s different from a lot of other similar services in so far as it’s really over the top. For a while, their text messages consisted of a joke about deep-frying a crystal ball. But recently, I got this:

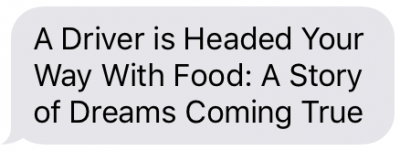

I can’t say why, but I was immediately annoyed. There’s too many exclamation points. There’s a typo, which is not really a big deal I suppose. But it’s the “pretty soon” that got to me. What kind of timeline is that? Grub Hub time estimates are almost always wrong, so what’s stopping you from making up some ETA this time? Then, I got this:

Really? Dreams coming true? Formatted as a book title? Look, this is too much.

But I shouldn’t beat up on Grub Hub too much. After all, my Birchbox subscription ships to “The Magnificent/Majestic/Glamorous Britney,” ModCloth tells me how great my taste is when I buy… anything, and Taco Bell absolutely adores me.

In 2014 when Facebook released research on how it had altered users’ moods, everyone was outraged. But how different is algorithmic mood manipulation from the cutesy familiarity or ego stroking and flattery that so many other companies engage in? Is it different because Facebook was deceptive? Or because it actively induced negative emotions? At the end of the day, whether it’s Facebook selling more advertising or Grub Hub getting more orders, the fundamentals of this affective marketing are the same. Build positive associations with a brand in an attempt to increase profit.

In The Happiness Industry, William Davies outlines just how pervasive affective monitoring and communication is. For Enlightenment philosophers like Hobbes, Rousseau, and Bentham the primary goal of social institutions should be to improve upon the human experience as it exists in the “state of nature;” that is, there should be a net gain of happiness and fulfillment that results from policy and market forces. Specifically in the case of Bentham’s utilitarianism and the cost-benefit analysis of policy decisions, the role of governments and markets in regulating the pleasure-pain continuum remains prominent. According to Davies, the moral and political imperative to be happy “originates with the Enlightenment. But those who have exploited it best are those with an interest in social control, very often for private profit.”

As such, the inducing, measuring, and regulating of happiness is quite a weapon to wield. As Davies writes, “those with the technologies to produce the facts of happiness are in positions of considerable influence, and… the powerful are being seduced further by the promises of those technologies.” Davies asks a somewhat provocative question: should we be against happiness?

Recently my partner David ordered food from Grub Hub and, after about 20 minutes, received this unfortunate message:

Aside from the gentle let down and the weird “thank you bye” follow up, it’s a dramatically different message than the typical happy-go-lucky Grub Hub tone. Perhaps that’s because this is such a grave matter that it would be inappropriate to make light of. For the record, they gave him $5 towards another purchase. Because if you can’t generate customer happiness with cutesy familiarity then you can always resort to cold hard cash.

How skeptical should we be with regards to services and technologies that try to induce happiness and familiarity in their customers? What meaning can we take away when Facebook, a behemoth corporation concerned primarily with advertising sales, tells us that it thought we might enjoy this memory from four years ago? Some examples are surely more insidious than others. While Grub Hub may be fairly benign, other services more heavily focused on surveillance demand greater scrutiny. For Davies, “any critique of ubiquitous surveillance must now include a critique of the maximization of well-being, even at the risk of being less healthy, happy and wealthy.”

When I worked in sales, we had all kinds of tricks to put people at ease, to get them to have positive associations with us. If someone objected to the sales pitch, we’d say “I can appreciate that, but let me ask you…” and then forge ahead. We’d ask about their kids, their jobs, their favorite TV shows—whatever we could think of to keep them talking about themselves. People love to talk about themselves. We’d make up stories whole cloth. I once told a woman my husband and I were building a house. At the time I had no husband, and definitely no house. I just wanted her to relate to me, to feel happy talking with me, and ultimately I wanted to make the sale. Maybe that’s why Grub Hub’s overly casual and friendly texts piss me off. They’re transparent, and I know they’re part of a larger game. So just bring me my sandwich. You don’t have to be my friend.

Britney is on Twitter