While those of us in the states were mired in election drama, across the Atlantic Brits came together to celebrate a sacred and time-honored holiday: #EdBallsDay.

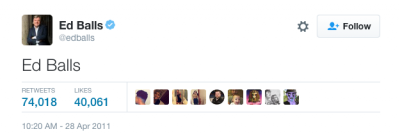

On April 28th, 2011, British Member of Parliament Edward Balls mistook the field for writing tweets for the search bar. Instead of searching for his name, he tweeted his name. And, because his name is Ed Balls, people lost their damn minds. At the time of this writing, the original tweet has over 70k retweets and 40k likes.

It is entirely unremarkable that a British MP whose last name is Balls got so much attention for tweeting his own name. What is remarkable is that people still remember every year. Many a think piece has been written on the ways the internet is destroying our brains, specifically our memories. Plato, the original think piece writer, recounted a story about some king who I can’t remember to make the point that writing would induce forgetfulness in those who learned it. Thousands of years later, people are still buttering their bread on the same idea. The internet ruins our memory. But what about the internet’s memory?

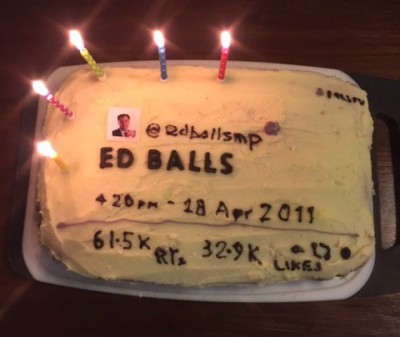

Ed Balls even made a cake to celebrate.

For Marshal McLuhan, what is “new” about a new medium is its capacity to extend the human sensorium to new scales. Speech allows us to transfer thought from our brains to the air and to other brains. Writing transfers these thoughts to a durable surface. Television broadcasts material sensations across the world. And with the internet, it often seems like everything is happening everywhere all of the time. This new scale requires new modes of cognition, such as Katherine Hayles’ “hyper attention” in which we pull information from multiple sources in quick succession, scan documents for key words, and frequently switch between tasks.

One of the results of this new scale of human cognition is the role of networked information technology in determining what we remember and how we remember it. The internet allows us to extend our memory outside of our individual minds, with important consequences for what gets remembered and how we are reminded of things. Something that has struck me throughout this election season is the work that Bernie Sanders supporters have done digging up old video clips and transcripts to write narratives that are lacking in major news outlets. The fact that no millennial remembers a speech Sanders made before the Senate in 1992 does not preclude their ability to find it, watch it, and use it to make a political argument. This becomes all the more important when these narratives are lacking from other vehicles of mediated memory. In other words, if mainstream news sources are failing to remember important historical moments and contexts, the affordances of digital media offer an alternative.

If every single individual who was party to Ed Balls’ tweet had to remember to celebrate April 28th each year, it’s unlikely that this fabulous holiday would have survived. But it only takes a few individuals, or perhaps one individual with a large enough audience, to remember given the affordances of Twitter. Over time, the effect snow balls—more and more people remember each year, and as #EdBallsDay gains greater traction it enters the consciousness of more people. Who knows; by April 28th 2021 it might be a national holiday.

So to my British friends, a happy belated Ed Balls Day. I’m sorry I didn’t send a card. I’m sure I’ll remember to next year though. Or, more likely, the internet will remember for me.

Britney is on Twitter.