[Edited to note: It’s been pointed out to me that I’m conflating transhumanism and posthumanism a bit here; gonna leave it as it is, but I agree and I just wanted to flag that.]

I’ve seen a lot of yelling about Lucy. The yelling is a major reason why I wanted to do some yelling of my own. And like so many times before, I find myself in the situation of feeling like much of what I could say has been said before by others, and better than I could, but I’m still going to yell a bit, because there are things about this film that trouble me profoundly, and I’m even more profoundly troubled by some of what people are saying about the film itself.

Before I continue, let me be up front and confess that no, I haven’t yet seen the film. I’ve seen trailers, I’ve seen clips, I’ve read a lot. But it’s absolutely true that a lot of my yelling is going to be mediated by things that probably aren’t properly contextualized within the plot of the film, or that have been mediated by the opinions and subjective readings of others. That’s just what I’m working with here and I own it.

Moving on.

So I could talk about a lot of the stuff in Lucy that people have pointed to as problematic. Since the release of the trailer, it’s become infamous for its racism; it’s about a white, blond, blue-eyed woman menaced and literally butchered by stock Asian mobsters, who also incidentally – at one point – at least appears to shoot a Taiwanese man for not speaking English. In Taiwan. People have observed that there are issues of intersectionality and white supremacist feminism at work here, given the celebration of some regarding Lucy‘s box office victory over the Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson grunty-growly-swordy vehicle Hercules (which has some of its own issues). There’s a lot here that seems pretty ugly. There’s a lot I could say.

But I want to focus on what the film appears to be saying about transhumanism and cognitive/physiological augmentation, and what both have to do – among other things – with the trope of the Strong Female Character.

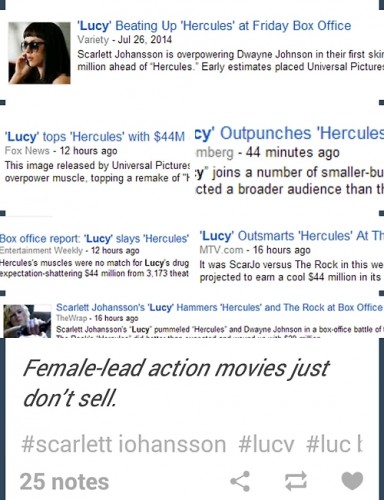

So far, the people who are lauding Lucy as some kind of feminist action flick have been focused on the above. We have a woman who comes to be in a position of enormous – eventually godlike – power, and the film is ostensibly about her claiming and use of that power and what it does to her and what it means for all humanity blah blah. Which is great; the idea that blockbuster action movies that feature women as the protagonists don’t do well financially is an old one now (by the way, there’s also the idea that they tend to suck, a la Ultraviolet, Catwoman, Tomb Raider, etc.) and clearly we’d all like to see examples that indicate things might go another way. At first glance, Lucy seems like it might provide that, but I think there are problems there, and I think they go beyond issues of white feminism.

Something for which the film has taken a lot of heat is its ridiculous premise: the urban legend that we only use 10% of our brains, so imagine what could happen if we could somehow access the other 90% (for anyone who still doesn’t know, this is completely and utterly not true; we use most of our brains in some way most of the time and all of it active all at once is called a seizure). I actually have less of a problem with that, because if nothing else the fact that it’s a myth is all over the place now.

But here’s the thing. Take a character – a female character. Subject her to horrendous physical injury and abuse in order to make her strong (guys, this is so not new and it’s so gross most of the time). Make the film about the process of her owning her new power. If you do this, you run the tremendous risk of creating a character who is her own MacGuffin, who exists only to become something else. Essentially, you no longer have a character. You’re left with a plot device, as Susana Polo observes in her review for The Mary Sue:

This isn’t development of Lucy as a person — from a hard-partying, poor-judge-of-character exchange student into a vengeful superhero — it’s transformation of her into plot device. She stops being a character and instead becomes a force that happens to other characters, which can work just fine in concept, as long as that character is not the protagonist whose fate and feelings we need to become emotionally involved in.

And what’s the nature of Lucy’s becoming? As she accesses more and more of her brain, she arguably becomes less and less human, which isn’t exactly a new trope, but in the context of a film that’s being celebrated for a Strong Female Character, it’s troubling:

As Lucy admits unequivocally in her first conversation with Morgan Freeman’s Professor Norman, the more of her cranial capacity she unlocks the less she feels bound by human desires and emotions, leaving Scarlett Johansson’s considerable acting chops in the back room as she delivers her lines in a monotone stretching the small space between bored to languid to just a little bemused.

We often construct human emotions as weakness. We also gender them female. Lucy might be a Strong Female Character, but as she leaves her frail humanity behind, she also becomes less of a whole person, with all the aspects of gender that human identity entails. A film that genuinely has empowering things to say about gender should probably be dealing differently with that.

This, to me, is one of the central problems with a lot of aspects of transhumanism, at least as I understand it: humanity doesn’t mean the same things to the same people, because we construct humanity according to social systems of oppression and domination. People of Color, women, queer people, people with disabilities, trans people, other gender-non-conforming people – dude, we exist in a state of diminished humanity. Your utopia of pure energy and intellect was not built with us in mind. Lucy may be seizing power, she may be turning into a creature of ultimate divine agency, but the context of her human identity will necessarily be abandoned. She won’t be a Strong Female Character, capitals or no capitals (more about that in a sec). She won’t be a character at all.

She will, in fact, literally be a flash drive.

And that’s the problem with the entire concept of the Strong Female Character: she’s not a character. She’s an archetype. She’s there to do a job, which is to be Female and to be Strong. So we see a character like this, who appears to be powerful, and I think a lot of us – including people who fancy themselves feminists – figure that’s enough to be happy about.

It’s not. We shouldn’t treat it like it is. This isn’t just unhelpful, it’s actively bad for representation in our fiction. As Shana Mlawski writes:

Some movies nowadays go even further. They pile up one awesome trait after another on top of this sexy female character, thinking that will make them “stronger.”…This Super Strong Female Character is almost like a Mary Sue, except instead of being perfect in every way because she’s a stand-in for the author, she’s perfect in every way so the male audience will want to bang her and so the female audience won’t be able to say, “Tsk tsk, what a weak female character!” It’s a win-win situation.

Except not.

A huge part of the problem, as Mlawski goes on to argue, is a lack of understanding – even and often especially on the part of writers – regarding what a “strong character” is. Most fundamentally, a strong character is a person – not necessarily a human person, but a person. They have complex motivations. They are fallible. They might even be intensely unlikable. They have rich histories and correspondingly rich presents, and “rich” does not mean “massively eventful and exciting”. Everybody has a rich history. Everybody is complicated. A strong character is recognizable in that respect. Mlawski actually makes the – to me, compelling – point that what we really need are more weak female characters, as in characters with flaws:

Good characters, male or female, have goals, and they have flaws. Any character without flaws will be a cardboard cutout. Perhaps a sexy cardboard cutout, but two-dimensional nonetheless. And no, “Always goes for douchebags instead of the Nice Guy” (the flaw of Megan Fox’s character in Transformers) is not a real flaw. Men think women have that flaw, but most women avoid “Nice Guys” because they just aren’t that nice. So that doesn’t count.

Lucy is, in the end, flawless. She’s perfect. Thanks to medical technology, she’s a god. And I don’t need to see the film to be highly skeptical about the idea that a film about a woman who becomes a god and whose purpose is to become a god is going to be a film about someone with any real depth.

So what? It’s an action movie, action movies are by definition stupid and not deep. They don’t need to be, they just need to get butts in seats for a couple hours. What’s the big deal?

The big deal is that a lot of people are talking about this film as if it’s some kind of feminist transhumanist unicorn. It’s not just another action movie. There is no way it could have been. That may not be fair, but the option was never open to it, so let’s not pretend it was. This is a film that features a woman in a male-dominated genre, so there is literally no possible way it was ever going to not be about gender.

And you know? I think we should be able to demand more from our fiction. Even our stupid fiction, because there’s a difference between stupid and bad, and there’s an even bigger difference between stupid and harmful. Action films are not deep character studies, no, but you only have to see a couple of the better ones to see how characters can be written interestingly and with some depth even in the context of shooting and explosions. We don’t single that out as an especially praiseworthy trait, but we like it when it’s there and generally on some level we notice when it’s glaringly absent.

I don’t get the sense that the people who are thrilled about Lucy are holding it to the same standard.

So no. I’m not happy, and I’m not satisfied. I don’t have the impression that Lucy has much in the way of good things to say about women, or about people, or about a relationship with technology that isn’t making being human simpler and purer but instead arguably messier and more complex. Yeah, it’s an action movie. Don’t care. I know we can do better than this.

And let’s please all agree to launch the Strong Female Character thing into the sun.

Sarah is a being of pure yelling on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 1

Why the “Ghostbusters” Reboots Outs Idiots Online | Dorm Room Television — March 10, 2015

[…] resembles struggles or characteristics that are inherently feminine. Those action parts are pretty much all about sex appeal. Finally, here comes a chance to put actresses in Hollywood in role opportunities they normally […]