I was working recently on a short essay about net neutrality and, in the process, ended up writing a much longer piece about net neutrality. My aim in writing that longer piece (below) was twofold: I wanted both to demonstrate that net neutrality isn’t too technical and complicated for normal people to understand, and also to trace out how a trio of closely related issues—net neutrality rules, regulatory classifications, and the push to convert all voice traffic to digital—fit together, as well as what their combination might mean for the so-called “open Internet.”

I was working recently on a short essay about net neutrality and, in the process, ended up writing a much longer piece about net neutrality. My aim in writing that longer piece (below) was twofold: I wanted both to demonstrate that net neutrality isn’t too technical and complicated for normal people to understand, and also to trace out how a trio of closely related issues—net neutrality rules, regulatory classifications, and the push to convert all voice traffic to digital—fit together, as well as what their combination might mean for the so-called “open Internet.”

SPOILER: You need to pressure the FCC to adopt strong net neutrality rules, and then you need to do a bunch of other stuff. Net neutrality isn’t enough, and neither Big Telecom nor Big Digital is talking about the pieces that will have the greatest (and most unequal) impact on Internet users.

Without further ado, here’s my attempt at a guided tour through roughly 18 years of Internet-related regulatory history:

The popular Digital Age mythology holds that, in the beginning, the Geeks created the Internet. And the Internet was without regulation or hierarchy, and the Geeks saw that it was good. Information flowed, ideas multiplied, and innovation was fruitful. Now, greedy Internet service providers (ISPs) have come to take that online utopia away—but such a utopia has never existed. And while fighting back against Big Telecom’s push for deregulation is a start, saving the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) watered-down net neutrality rules is not enough to create the “open Internet” of slogans and fantasies. Much of the net neutrality battle comes down not to principles and ideology, but to Big Telecom and Big Digital fighting each other over power, profit, and control.

The popular Digital Age mythology holds that, in the beginning, the Geeks created the Internet. And the Internet was without regulation or hierarchy, and the Geeks saw that it was good. Information flowed, ideas multiplied, and innovation was fruitful. Now, greedy Internet service providers (ISPs) have come to take that online utopia away—but such a utopia has never existed. And while fighting back against Big Telecom’s push for deregulation is a start, saving the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) watered-down net neutrality rules is not enough to create the “open Internet” of slogans and fantasies. Much of the net neutrality battle comes down not to principles and ideology, but to Big Telecom and Big Digital fighting each other over power, profit, and control.

At its most basic level, the contemporary idea of “net neutrality” is that your ISP should treat equally all information traversing the network either to or from your device. Your ISP should not privilege some websites by letting you exchange information with their servers more quickly, and nor should it penalize other websites by making your exchanges with their servers more slow (or simply impossible). While your ISP may sometimes make your whole connection slower—particularly if you approach any usage or bandwidth limits—it should not pick and choose which information does or does not get through to you. It should deliver all pieces of information (or “packets”) to you equally, regardless of where they have come from or where they are going. In short, your ISP should be neutral.

In practice, however, your ISP probably is not neutral—and if your ISP is a giant media-telecom conglomerate, there’s a good chance it’s fighting to be even less neutral. Last month, the FCC voted 3-2 to approve its latest proposal for net neutrality rules. That approval means that the public (including corporations) now has until July 15th and September 10th to give feedback before the official vote, which is expected sometime this fall.

Titled, “Protecting and Promoting the Open Internet,” the FCC proposal is intensely controversial, and more so for what it leaves open than for what it explicitly permits or proscribes. The two biggest issues are whether the FCC might (re-)reclassify broadband Internet providers as “telecommunications services” instead of “information services”, and also whether the FCC might allow ISPs to charge digital content providers for preferential treatment on the networks the ISPs control. Of equal importance—though the issue has gotten far less attention—is the fact that the 2014 rules are unlikely to apply to wireless (mobile) Internet connections.

If we want to understand what all this means, we have to look back to the Internet’s complicated political, economic, and social histories. But if we want to understand what the state of regulation should be—and why it matters—we need to look not to the Internet that has been, but to the Internet we want in the future. If the Internet we want is, in fact, an open Internet, then we have our work cut out for us—and we must begin by defining, in technology-neutral terms, exactly what we mean by words like “open” and “neutral”. Following that, we need to make some major changes to our federal policies, our state laws, and our local and national network infrastructures.

Network Neutrality

Colloquially, we use the term “Internet” to reference two different (if closely related) things. Sometimes we mean the tangible infrastructure of servers, cables, and wires (as in, “Who broke the Internet?” while waiting for a website to load). Other times, we mean the information we can access via that tangible infrastructure (as in, “Why are there so many cats on the Internet?”). A big part of the fight over net neutrality is that these two pieces, the infrastructure-Internet and the information-Internet, are at odds over the profits and costs of doing digital business.

Until 2002, the FCC considered the information-Internet to be “content” and the infrastructure-Internet to be “carriage.” In practical terms, this meant that the infrastructure-Internet was in the same regulatory category as telephone networks, and so was subject to certain restrictions and obligations. (During the dial-up era, of course, a large part of Internet infrastructure simply was the telephone networks.)

Even subject to regulatory oversight, however, some Internet carriage companies were not behaving like the backbone of a networked nirvana. In fact, it was Tim Wu’s experiences marketing non-neutral network hardware for a Silicon Valley start-up that first led him to write the 2002 memo in which he coined the term “network neutrality.”

Although “net neutrality” is now often used to reference a “level playing field” for data transfer, Wu’s original framing was more modest: he sought to establish both “forbidden and permissible grounds” for traffic discrimination by ISPs, first by laying out principles and then by delving into the legal and technical specifics (as they stood at the time). Generally, “permissible” discrimination pertains to an ISP’s own network, whereas “forbidden” discrimination pertains to networks that connect to an ISP’s network. (What we think of as “the” Internet is, by design, really a decentralized network of many other networks.)

To use the “gaming” example from Wu’s memo, let’s say that ISP, Inc. has congestion on its network because some of its customers are playing a bandwidth-intensive game on GameSite.com. It would be forbidden for ISP, Inc. to block its customers from accessing GameSite.com, because it would unfairly harm GameSite.com’s business. It would be permissible, however, for ISP, Inc. to impose bandwidth limits and to charge its customers extra for raising those limits. (It’s also worth pointing out that ISPs make money by selling bandwidth to their customers; if ISPs can’t cap their customers’ bandwidth, it becomes difficult to sell them any more of it.)

Wu’s rationale for classifying the bandwidth cap as “permissible” was that, if customers elect to stop using GameSite.com rather than start paying ISP, Inc. for more bandwidth, that’s a “market decision” rather than ISP, Inc. imposing its own self-interest on GameSite.com. Importantly, Wu’s 2002 memo seeks to prevent harm to businesses and restrictions on individual ISP customers; it does not consider harm to the content-Internet or to individual people. And while, literally speaking, “discriminate” just means “to differentiate,” Wu’s examples focus primarily on the issue of ISPs restricting traffic in and out of their local networks. The memo does not explicitly address whether ISPs could or should privilege some inter-network traffic, and nor does it address “peering” (or how networks connect to other networks).

By 2004, Wu’s network neutrality memo had found a sympathetic ear in Michael Powell, who at the time was chair of the FCC. Under Powell, the FCC released a 2005 policy statement to “encourage” four “principles” consistent with network neutrality. Powell’s FCC also elected, however, to classify cable Internet under “information services” in 2002, and to reclassify DSL (which runs on telephone wires) under “information services” in 2005. This de facto deregulation of broadband—combined with the toothlessness of a “policy statement” and a permissive attitude toward mergers—set the stage for the litigative melee that surrounds net neutrality today. (It’s worth noting that Powell went on to become President and CEO of the National Cable & Telecommunications Association.)

Regulation and Litigation

The current fracas began in 2008, when the FCC ordered Comcast to stop blocking BitTorrent traffic on its networks. (BitTorrent is a kind of file-transfer software.) Comcast appealed the order on the basis that, because ISPs are classified as information services rather than telecommunications services, the FCC lacked jurisdictional authority to issue the order in the first place. Comcast won its appeal in 2010, and the FCC responded by formally adopting new rules.

The 2010 rules banned ISPs from blocking or slowing transmission of “lawful” content, but said only that ISP “pay for priority” practices would be “significant cause for concern.” The FCC did not reclassify ISPs as telecommunications services, and stated repeatedly in footnotes that the new rules did not apply to peering agreements between ISPs. Verizon appealed the 2010 rules before they were even in effect, and won its appeal in January of 2014 by using the same classification/jurisdiction argument that Comcast had used before it. At that point, all of Internet culture looked at the FCC, shook its head, and sighed (or screamed), “#doingitwrong.”

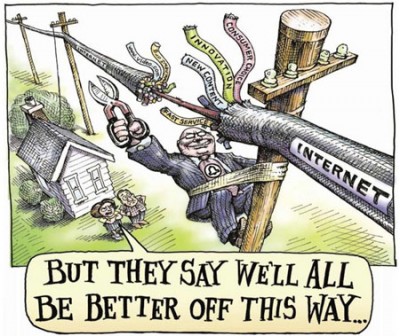

Now the FCC is trying again. The 2014 edition of (pseudo-) net neutrality would ban ISPs from blocking access to “lawful” content, but merely comes to the “tentative conclusion” that pay-for-priority practices would be “subject to scrutiny” and banned if they are not “commercially reasonable.” Though the FCC muses aloud about whether to reclassify broadband providers as telecommunications services, it makes no clear move to do so. And while the FCC once again declines to address the issue of peering, this time it points out that paid peering agreements are a great loophole for ISPs to circumvent net neutrality. While the document is just that—a proposal, rather than finalized rules—things are not looking good for the open Internet.

Predictably, no one is happy with the 2014 proposal save current FCC chairman Tom Wheeler. (It’s worth noting that Wheeler is a former President of the National Cable & Telecommunications Association and a former CEO of the Cellular Telecommunications & Internet Association.) Big Telecom—companies like AT&T, Comcast, Verizon, and Time Warner Cable—loves regulation in the form of municipal monopoly support, but protests vociferously whenever the FCC intimates that the Internet is part of its regulatory purview. The net neutrality rules are no exception, though Big Telecom has been careful to keep its tantrum out of network and cable news. (Some have argued that the FCC has no intention of reclassifying, and that the specter of reclassification appears just to give Big Telecom and the far right something to attack.)

On the other hand, Big Digital—companies like Google, Amazon, and Facebook (etc), which are the targets that make pay-for-priority (and paid peering) practices so appealing to Big Telecom—has no desire to pay, but knows that no Big Digital company will have a choice once even one of the others signs up for “priority” service. Netflix has come out in favor of extending net neutrality rules to peering agreements as well, largely because Comcast (allegedly) slowed Netflix traffic in order to extract a paid peering agreement earlier this year. When it comes to net neutrality, even Silicon Valley libertarians love regulation and strong government oversight.

Meanwhile, both Big Digital and Smaller Digital maintain that pay-for-priority practices would “stifle innovation, entrepreneurship and free expression” by making it difficult, if not impossible, for start-ups and other new companies to enter the competitive arena. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) warns that throwing out net neutrality rules could lead to (increased) censorship by ISPs, while the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) has come out against both Big Telecom and the FCC. Ordinary people—at least, those who are paying attention (and who care about being able to access sites that aren’t part of Big Digital)—are upset as well.

Infrastructure (This is a Big Deal)

Lurking beneath the surface of the net neutrality debate, however, is another issue: aging network infrastructure. Two of the biggest ISPs, Verizon and AT&T, are former Baby Bells (legacy telephone companies); as such, they are sitting on a lot of old copper telephone wire. While most trunklines (or “arteries” between switching centers) have been upgraded to newer, faster, optical fiber cables, the so-called “last mile” networks—the “capillaries” that connect to individual homes—are overwhelmingly still the same twisted wire networks that Ma Bell installed while building out the public switched telephone network (PSTN) between 1920 and 1970.

The old PSTN networks pose more than a few problems for Verizon and AT&T. They’re not great for Internet service because, even when the wires are in perfect condition, information can’t travel as quickly through copper wire as it can through coaxial cable or optical fiber cable—and the PSTN networks are no longer in perfect condition. Yet telephone service is a public utility, and universal service policies obligate telephone carriers to keep their networks working for all customers. Though AT&T et al are pushing for further deregulation with the help of the American Legislative Exchange Council (or ALEC, a group perhaps better known for its private prison profiteering), Big Telecom is not yet entirely off the hook. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.)

Since copper can’t compete with coax or fiber, none of Big Telecom wants to put money into fixing the whole PSTN system just to maintain universal service. Rewiring the entire country with fiber, however, would be tedious and expensive. In recognition of this, the FCC authorized years of surcharges and fees to help offset the cost of upgrading the networks and extending universal service to broadband. In response, Verizon and AT&T did each laid some fiber. Then, they started lobbying to get out of universal service.

This is particularly problematic given that each has stated its intention to discontinue PSTN service and force all customers onto either digital landlines (where broadband is available) or wireless (where broadband is not or is no longer available—which means only wireless Internet access, as well). Less than a decade ago, Big Telecom’s ISP arms tried to block network traffic from “voice over Internet protocol” (VoIP) software, because VoIP competed with Big Telecom’s telephone-carrier arms. Now, citing declining landline subscriptions & the cost of maintaining PSTN networks, AT&T and Verizon are moving instead to join Comcast, Time Warner Cable, and others in offering digital voice services only. Big Telecom has become VoIP’s biggest proponent.

The way Big Telecom imagines it, in the near future, all telephone and Internet traffic alike will be digital. For people who live in dense urban areas (and who can afford a broadband connection), much of this traffic will travel via coaxial cable or, for the lucky few, fiber. (Note that, in a sense, “fiber” is a misnomer; few Verizon FiOS or AT&T U-Verse customers have fiber connections that run all the way to their homes. Most homes still connect to the fiber network via old PSTN lines.) For people who can’t afford home broadband, however, or who live in areas that Big Telecom deems insufficiently profitable to merit installing or maintaining broadband, telephone and Internet traffic will travel via wireless networks like 4G, LTE, or EDGE (where available).

Put it all together and…

Here is where all the nerdy details about infrastructure and net neutrality start to matter—because they determine whether the Internet’s future is looking “bad,” or “worse.” On the worst end of the spectrum, the 2014 net neutrality rules fail. Mergers and deregulation result in three or four huge companies controlling a vast portion of U.S. Internet access. Unchecked either by competition or by the FCC, Big Telecom privileges, discriminates against, or even blocks traffic on local networks, and does so with impunity. Both online and on TV, you see what Big Telecom wants you to see. The conversion of all voice traffic to digital lets Big Telecom abandon the old PSTN networks and provide upgrades only to the most desirable customers while leaving everyone else with inferior, more expensive wireless service. Big Telecom likely argues that, because all voice traffic is now digital, telephone should be a minimally regulated “information service” as well.

On the better end of the spectrum, the 2014 net neutrality rules are adopted—but things are still pretty bad. Mergers and deregulation result in three or four huge companies controlling a vast portion of U.S. Internet access. Thanks to local monopolies, the ALEC legislation, and the advantages of size, Big Telecom is still mostly unchecked by competition. The FCC prohibits Big Telecom from blocking or discriminating against “lawful” traffic, but “pay for priority” practices can easily become traffic discrimination by an inverse approach and another name. (This is analogous to the difference between merchants charging their customers a fee for using credit cards—which is illegal—versus offering customers a discount for using cash, which is allowed.)

Paid peering practices are also still allowed, so Big Telecom is further incentivized to skip upgrading local networks in order to make paid peering agreements more appealing to Big Digital (as happened with Netflix). Meanwhile, Smaller Digital can afford to pay neither for peering nor for priority, and slowly fades away as users stop visiting sites that take too long to load. The conversion of all voice traffic to digital lets Big Telecom abandon the old PSTN networks and provide upgrades only to the most desirable customers while leaving everyone else with inferior, more expensive wireless service. Oh, and, about that: the 2014 FCC proposal “tentatively conclude[s]” that, as in the 2010 net neutrality rules, it’s fine for wireless ISPs to block particular websites or apps. The FCC’s wireless net neutrality is even more diluted than its broadband net neutrality.

Given a choice between the FCC’s net neutrality and no net neutrality, you want net neutrality. But if you care about having an open Internet, net neutrality is just the beginning of what needs to happen.

Tom Wheeler has been widely quoted as saying, “There is one Internet. Not a fast Internet. Not a slow Internet. One Internet.” His statement, however, is neither technically nor socially accurate. Big Digital, Smaller Digital, and other content providers are already stratified by ability to pay for their own Internet connections and for infrastructure (such as servers or hosting services), all of which already impact how quickly or slowly their sites load. Even if the 2014 net neutrality rules are adopted, this speed difference stands to grow larger. End users, too, are already stratified by what kind of access they can afford and by what types of service are available where they live. This stratification is not sociologically neutral: a 2012 study found that men and white people are more likely to have home broadband, while “young adults, minorities, those with no college experience, and those with lower household income levels” are more likely to have mobile Internet access only. If broadband becomes a resource available only in wealthy neighborhoods, these stratifications will intensify.

Certainly “maximum regulation” of Big Telecom would go a long way toward curtailing discriminatory ISP practices. It could also be extended to eliminate paid-peering agreements, to mandate universal broadband service, and to apply net neutrality equally to wireless and broadband ISPs. Municipal fiber would make high-speed Internet access more affordable and more widely available, particularly in urban areas; it would also provide sorely needed competition for Big Telecom (which is why Big Telecom has been so diligent about attempting to block it). These are all important, and necessary, steps.

Thinking Bigger

Internet “openness,” however, is more than a technical or even regulatory problem. Consider the radical idea that Internet openness isn’t just ensuring equitable data transfer over network infrastructure, but creating the conditions of possibility for equitable participation. Is it really an open Internet when women journalists, filmmakers, professors, bloggers, gamers, and others receive rape threats and death threats, sometimes to the point of quitting their jobs or retreating from public life? (See here for even more examples.) When a Black woman gets less harassment on Twitter, and more respect, just by changing her user photo to a picture of a white man? When homophobia leads to death threats against a five-year-old? Pundits love to point out that women (etc) do not have a monopoly on being harassed, or to claim that most death threats are just “idiotic emails,” as if either line of reasoning negates the cumulative chilling effects that follow from pervasive abuse. At some point, we have to start asking whether “protected speech” should be the right to say harassing and abusive things, or the right to speak without being harassed and abused.

What do death threats have to do with net neutrality? Precious little. And that is precisely why, if you want an open Internet, you can’t stop at pressuring the FCC to adopt its proposed net neutrality rules. You can’t stop even when you (someday) get municipal fiber. We won’t have an open Internet until we have an open society.[i]

Whitney Erin Boesel (@weboesel) is a fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society, a visiting scholar at the MIT Center for Civic Media, and a PhD student in sociology (among other things), though her views here are her own.

Lead image credit: BrokenCities; other images from here, here, here, here.

———————–

[i] It should go without saying that an “open” society is not the same thing as a society in which privacy has been abolished, or in which radical transparency has been forced upon less powerful actors by more powerful actors. If anything, Silicon Valley’s consistent misapplication of radical transparency (it’s supposed to go up a power gradient, not down) has made ours a less open society.

Comments 3

Quick links (#12) | Urban Future (2.1) — June 13, 2014

[…] Background to the net-neutrality argument. […]

Library: A Round-up of Reading | Res Communis — June 30, 2014

[…] (Almost) Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Net Neutrality – Cyborgology […]

Commodifying Voice: The Net Neutrality Debate » Cyborgology — November 4, 2014

[…] Erin Boesel does a fantastic job laying out the policy and delineating a strong argument in support of Open Internet. I want to take a bit of a simpler […]