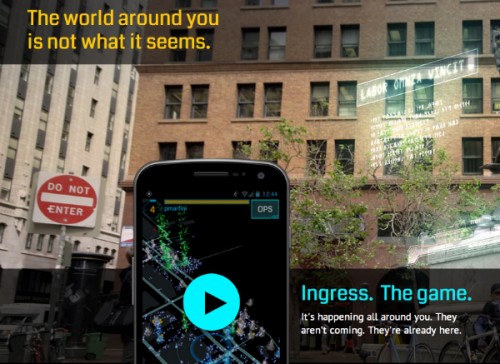

One of the most interesting things to watch in the usage trajectory of any form of technology are the ways in which it’s used that no one really anticipated, but that seem perfectly sensible and obvious after the fact. One of those that I actually found out about only this week – really, I should have known about it before – is Ingress, a game played on mobile phones that sorta kinda comes from Google, and whose players are intense enough about it that one of them flew to a remote location in Alaska in arguably dangerous conditions in order to complete a game task.

Essentially, Ingress is a game of augmented strategic geography. Players of two factions compete to “claim” locations and sections of land all over the globe, creating triangular links. The premise in terms of the game mechanics is relatively simple, but the game’s narrative is where things start to get complicated:

The game mixes the real world with science fiction. The player factions, the Enlightened and the Resistance, are more or less at war. More recently, they’ve been working at cross purposes to unite the shards of a broken man named Jarvis, ferrying these digital treasures around the world, to either unite them for one faction in San Francisco on December 14, if the other faction can’t unite the majority of them on that same day in Buenos Aires.

Again, one of the things that’s remarkable about the game are the lengths to which its players are willing to go in order to play, and the degree to which they become engrossed in the game’s world. It’s entirely possible that they would do so without a complex storyline in which the stakes are incredibly high, but I’d argue that it’s much less likely. Basically, what Ingress represents is an example of a technology being used in a way that was not explicitly predicted by its initial designers – though other designers came along and made use of existing affordances of possible design – and being given its power to engage through participation in an interactive narrative.

So one of the things I’m primarily talking about here is those affordances, and how they shape use in some unexpected ways. And also how important creative storytelling seems to be in a lot of these cases.

It’s useful at this point to think of affordances in two separate ways: designed affordances, or those affordances intended by the designer, and perceived affordances, or those possibilities for use identified by a user. There’s going to necessarily be some overlap here, but not always, and I want to talk about these things as largely mutually exclusive. Someone designs something according to an intended use, and a user comes along and does something else with it.

Again, Ingress isn’t a totally perfect example, because what we have here are designers building on top of existing design. But ten or fifteen years ago, this still would have been a fairly radical departure from the understood use of a cell phone. The designers of Ingress perceived affordances for their own design and took advantage of it. And they stuck a story in there, because people like stories.

People also want to tell stories. It’s a cognitive compulsion, a primary feature of how our brains work. We literally can’t exist as self-aware human beings in the way that we do in the absence of narrative, which is one of the reasons why studies of narrative often serve as places where literary theory and cognitive science intersect. Give us a technology and we’ll figure out a way to make narrative use of it, even if it’s only in the most individual terms, even if our perceived affordances in doing so are hugely different from the existing designed affordances.

This is where it’s appropriate to talk about fandom. Specifically, fandom roleplaying.

For those who don’t know, fandom roleplaying – “RPing” – is when participants in fandom take on the roles of pre-existing characters and play out interactions with other characters. These interactions are sometimes written out as conventional narratives – as found in traditionally written fiction – and sometimes as direct dialogue punctuated with brief descriptions of action (sometimes between asterisks). Plotlines can be simple or fabulously complex, with rich interpersonal relationships that include long played histories. “Games” can sometimes continue for years; one with which I used to be involved is almost a decade old.

The online media in which RP appears is diverse, though for a long time I was only aware of the “threaded” format found on LiveJournal, Dreamwidth, and similar sites. But there’s RP everywhere. There is RP on Tumblr. There is RP on Facebook. There is RP on Twitter. There is RP anywhere that fandom can possibly make the logistics work. There is even – and this is the one that blew my mind and to which I want to call special attention – RP on Goodreads.

The thing is that, while the other sites that I mentioned above are pretty conventional blogging and social media sites that allow for a fair degree of flexibility in terms of use, Goodreads is a site intended specifically for reading, recommending, and reviewing books. It has a lot of other uses, and a major – even primary – social component, but it wasn’t made for RP. It wasn’t made for anything even vaguely like RP. But, with apologies to Ian Malcom, fandom finds a way.

Goodreads wasn’t designed for RP. But the affordances are there.

This is not to directly link affordances and narrative in every case – obviously these categories are much too broad for that to work. It’s just to highlight the ways in which human beings appear willing take advantage of just about any and every chance to work narrative into the use of technology. Affordances are, by definition, elements of use that reveal human creativity, and storytelling is a fundamental part of that.

So really, I shouldn’t have been so surprised to see RP on Goodreads. I still don’t get it, but I should have expected it. Nothing would be more “natural”, to the extent that we want to use that word at all.

Sarah roleplays as themselves on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 1

Thomas Wendt — December 8, 2013

Check out Don Ihde's work on the multistability of technology if you haven't yet. He talks a lot about the intended outcomes of designers and the actual outcomes once a product is in users' hands.

I'm not sure I follow your point about affordances. In Gibson's articulation, affordances are necessarily part of the environment, and designers are in the business of designing affordances. But you seem to be talking about the narrative and social implications of the game. Am I reading that incorrectly?