We did it! According to the Editors* of n+1, Sociology—in fact, the underdog coming from behind, Critical Sociology—has won the cultural debate. Critical thinking about power and how it constructs individuals is now universally applied. The bad news is that critical thinking about power hasn’t solved inequalities, and therefore we have “Too Much Sociology.” The Editors of n+1 fail to understand their topic, fail to cite accurately, and, fundamentally, have written a piece that is logically flawed from even its own position.

There are many good reasons to dismiss this essay, but let’s first skip over the most inaccurate parts to explain why the essay does not even make sense on its own terms. There is a good argument that Bourdieusian theorizing can be used for regressive ends. But: that is a Critical Sociology argument! Interrogating exactly how an episteme can be co-opted, even by that of which it is critical, is what critical sociology does. The article uses critical sociology as its method, as its logic, in order to conclude—against its own logic—against doing critical sociology. Hilariously, the essay is a work of critical sociology about critical sociology that is critical of critical sociology. (Let’s keep open the possibility that this is a late April Fools Onion-style parody).

“Too Much Sociology” is the essay equivalent of hipsters making fun of hipsters, seemingly unaware that their anti-hipster position is the height of hipsterdom. The essay discusses “the Sociologists” as if they are separate from what the essay is itself doing, and goes on and on about critical sociology seemingly unaware of itself as a critical sociology essay. Doing reflexive critical sociology of critical sociology is a well-worn tradition within critical sociology. The strategy the article uses, and the arguments it wants to make, are for more critical sociology; instead, the essay incoherently and illogically asks for less sociology. And, yes, I fully understand that my critique here is also critical sociology; the difference is that I am aware of that and won’t then develop an illogical conclusion. My response here isn’t as much a disagreement with their argument as saying that it simply doesn’t make sense on its own terms. Trying to create a theory that interrogates the links between power, discourse, and identity has as much of a chance of being outside of critical sociology as trying to put on an outfit that is outside the system of fashion.

Put simply: personally rejecting analyzing the link between status and taste doesn’t mute that link. Indeed, it is simply one more move in the same game: rejecting taste-status is one more taste status, as is my rejecting of their rejecting of taste-status. To escape the taste-status logic, the authors would need to show why the link is false, but instead, they make an argument for taste-status by showing how the taste for Bourdieusian theory reaffirms status.

And that’s not a terrible argument to try to make, but, again, the authors give it exactly the opposite conclusion the argument should call for: more and better critical sociology. (Seriously, the essay is the logical equivalent of ‘2 + 2 = -4’).

Well, I’m being too nice: The authors do not even make the ill-concluded argument in a way that remotely approaches being convincing. And I say this as a fan of the general project of showing how critical sociology can be done poorly, because I’m a critical sociologist. The project is akin to those who look at the commoditization of dissent—say, how a Che Guevara t-shirt at Urban Outfitters exemplifies the way capitalism is so good at co-opting things that even anti-capitalism can be used to support capitalism. This issue is well-known to theorists of dissent, who mostly do not stupidly declare “Too Much Dissent” as the n+1 logic does. Similarly, as is described in the article, if Amazon’s Jeff Bezos is using taste-power logic to reinforce his powerful enterprise, we should indeed be critical of that as a taste-power move (and also our own critique as its own taste-power move). It’s hard, and it’s awkward, but it’s better than leaving the link unexplored.

Further, the n+1 Editors are sloppy in explaining what “critical sociology” is to them to begin with. The most charitable reading is that the Editors are theorizing from the perspective of interrogating the power dynamics behind identity, taste, behavior, consciousness…everything. They do not simply mean The Frankfurt School. They mostly center on Bourdieu and his adherents. That’s, of course, not the whole of critical sociology. They also mention Latour (whom they wrongly cite as “radical”), Foucault (um, who wasn’t a sociologist), and a bunch of other men: Giddens, Derrida, Guillory, Khan. The only woman mentioned is Pascale Casanova, and the n+1 Editors go on to completely ignore the critical sociology centered in queer theories, critical race theories, feminist theories, and so on, in order to argue that all critical sociology should be thrown out.

[FYI: Beyond just ignoring women critical sociologists who make the points that the n+1 Editors claim as their own without attribution, the Editors also use universal male pronouns.**]

So much critical sociology—especially from queer, intersectional, and many other perspectives—is simply ignored to make claims such as,

Thinking of everything as a scripted game show hasn’t led to change. Instead, sociological thinking has hypostatized and celebrated the script

This is sometimes true. But is it always true? And true for the critical sociology that was left out of the n+1 analysis? Do, say, feminist or queer theorists who argue that gender is performed really reify and celebrate the gender-scripts that society hands us? Making that argument is going to need some evidence, and that project would at least need to actually be aware of and cite these and other strands of critical sociology.

It is this kind of sweeping and inaccurate statement that precludes the n+1 Editors from making what could have been a worthwhile argument. They claim that “imagin[ing] …networks of power,” for instance, has become “the way everyone thinks,” and that,

sociology of culture has achieved such a dominant share in the contemporary “marketplace” […]

sociology cannot provide us with internal reasons for its ever-rising prestige

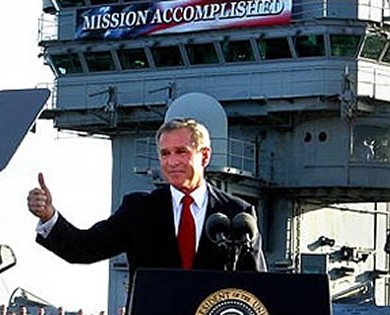

Yay! Sociology is finally dominant, and the way that “everyone thinks”. Mission accomplished! First, um, der, no. Second, of course there is there is a critical sociology of sociology. Third, the idea that “everyone” looks to networks of power is so radically and plainly incorrect that it’s offensive. It’s offensive to those not in the tiny ultra-privileged world that can be bored with questions of power, domination, inequality, resistance, and so on, because these questions make looking at art “more awkward.” Fuck that, go read a YouTube comment. Most of us live in worlds where the links between power and identity, knowledge, and behavior are unquestioned, and where bigotry comes from places other than mean critical theorists. Teaching Bourdieu to undergrads is still a challenge, trust me—though I wouldn’t mind visiting the Bourdieu-Foucault Disneyland the authors live in, where critical sociology holds such sway.

The sweeping-statement silliness reaches its climax as the Editors state,

Being no closer to a society free of domination, injustice, and inequality than we were in 1993, we may ask whether the emergence of cultural sociology is a symptom of a problem that sociology itself cannot solve.

How dare sociology not solve domination, injustice, and inequality in two full decades! What do we throw out next? You know, feminist theory has been around for a while….

The article concludes by critiquing the status of critical sociologists who see themselves as outside the system of power-taste, saying

It is the sociologist who is uniquely qualified to provide explanations for us, which have to do with feelings of status or desire for recognition, sublimated self-interest […]

The secret allure of critical sociology lay in making certain susceptible members of dominant classes hear an appeal to some transcendent sense of radical justice and fairness

Yes, that’s a good critical sociological critique—you know, critical sociology, that logic we’re being asked to abandon. Indeed, this is a well-worn point within critical sociology that asks for radical self reflexivity. The Frankfurt School gets hit with this point all the time by, you guessed it, other critical sociologists. Indeed, this essay, unlike good critical sociology, suffers from what it critiques: It somehow thinks it is beyond the power-taste system, unaware of itself as yet another move in that system. And, importantly, in the process of making a logically incoherent argument, it has gone out of its way to erase the critical sociology done primarily by those who are not white men.

I wish this response was more of a good-faith challenge to their thinking, but this n+1 piece is so attention-seeking, conversation-derailing, misinformation-filled, and logically-flawed that I’m left fully dismissing it. I questioned even giving it the attention of a rebuttal on this blog. Perhaps I shouldn’t feed the troll, and n+1 is certainly acting trollish here, but, as I’ve argued before, I don’t think outlets with influence can troll or derail a conversation because they set the conversation, and thus should be responded to. The magazine is well-known in certain circles and I think sociologists should be aware of what this certain group of slightly-influential people are saying about the discipline. And n+1 demonstrates exactly why we need more, better sociology.

Nathan is on Twitter [@nathanjurgenson] and Tumblr [nathanjurgenson.com].

——–

Here are two more responses to n+1‘s essay, first, by Jay Gabler:

Next, by Jennifer C. Lena,

——–

*The essay is attributed to “The Editors”; going to n+1’s About page, we see the “Editors” are Carla Blumenkranz, Keith Gessen, Mark Greif, and Nikil Saval, so this who I’m led to believe wrote this.

**e.g. (among others),

The ordinary person, genuflecting before his unfreedom, cries “uncle”

Comments 14

whitneyerinboesel — April 15, 2013

nathan, thank you for this. as you know, i found the n+1 piece particularly irksome, but this was a delight to read; i've filed your rebuttal under Funny Because It's True (so true, in fact, that it kind of hurts).

i wanted to chime in and add my own two cents——not to be all 'critical sociology' about it——about how very desperately "The Editors" of n+1 need to turn a critical eye on their own privilege, because their conflation of their own idiosyncratic social microcosm with the whole of the social world goes straight past "merely wrong" and into "deeply offensive." it's not often that an article manages to lose me (alt: anger me) by *the second sentence*, but the n+1 Editors pulled both off with this gem:

"Think back to the first time you heard someone casually talk of “cultural capital” at a party, usually someone else’s inglorious pursuit or accrual of it; or when you first listened to someone praise “the subversion of the dominant in a cultural field,” or use the words strategize, negotiate, positioning, or leveraging in a discussion of a much admired “cultural producer’s” career."

if "everyone" is now a critical sociologist, where does that leave all the people who can read that sentence, but have no idea what it means? or the people who can't read that sentence at all? not to mention, i'm thinking back...and thinking back...and going so far back into the past that i'm wrapping around to a hypothetical future, because——even as a member of a theory-intensive sociology PhD program——these things have NEVER HAPPENED to me. who are these Editors, and what planet do they live on? if they're off in "Bourdieu-Foucault Disneyland" (as you say), it might indeed be a fascinating place to visit and study for a day, but it sounds to me like they're just at some kind of cocktail party from hell.

PROTIP for n+1 Editors: conversations and parties are like twitter. if they're awful or tiresome, it's not the format that sucks; it's your choice of whom to engage. the problem is not that the world is full of people doing critical sociology badly, or even people doing critical sociology at all; the problem is that that you (apparently) spend time with people who are very privileged, and very annoying.

in the spirit of friendly assistance (one critical sociologist to some others, since i guess we're all critical sociologists now), i would like to cordially invite the n+1 Editors to leave the cocktail party from hell and come speak with *any* of the people i talk to——especially my relatives, the students i've taught, my friends struggling to make ends meet, or the people who live on the street underneath my window. there's hope, Editors...all sorts of places where critical sociology is just beginning to make inroads, or has yet to infiltrate at all.

in other words, nathan states,

"It’s offensive to those not in the tiny ultra-privileged world that can be bored with questions of power, domination, inequality, resistance, and so on, because these questions make looking at art 'more awkward'"

...and i couldn't agree more. given that we're all steeped to saturation in critical sociology, The Editors' failure to use said critical perspective to check their privilege before they clicked "publish" on this is even more appalling.

Elly/QRG — April 16, 2013

'Perhaps I shouldn’t feed the troll, and n+1 is certainly acting trollish here, but, as I’ve argued before, I don’t think outlets with influence can troll or derail a conversation because they set the conversation, and thus should be responded to. '

I think your concept of 'troll' and 'trolling' is flawed. The way I see the term 'troll' is it is all about the person using the term - so in this case you use the word in order to undermine and discredit that which you critique. But as someone who gets called a 'troll' on numerous occasions, not for 'derailing' conversations but for simply trying to *have* conversations that people don't really want to have, I object to the 'troll' concept.

We are reading Foucault at the moment. To paraphrase him horribly, maybe 'the only ethical thing to do with discourse is to 'derail' it'.

A meta analysis | Memoirs of a SLACer — April 16, 2013

[...] article claiming that there is “too much sociology” (as if that is even possible!) is by Nathan Jurgenson at The Society Pages. Jurgenson focuses on the ridiculousness of writing an article using critical sociology that is [...]

J — April 17, 2013

This article reminded me of this scene in a favorite movie of mine:

Steve: When you come to a place like this, you have to ahve an act. So I thought a) I could just leave you alone, b) I could come up with an act, or c) I could just be myself. I chose "c". What do you think?

Janet: I think that a) you have an act, and that b) not having an act is your act.

Paletleme Amirliği – Nisan 2013 | Emrah Göker'in İstifhanesi — April 19, 2013

[...] “Herkes sosyolojik analizci olmuş” iddiasını abartılı bulduğum ama okunası yazı: “Too Much Sociology”. Buna cevap iç ısıttı: “More, Better Sociology”. [...]

More, Better Sociology » Cyborgology | Sa... — April 28, 2013

[...] [...]

Austen — May 27, 2013

I've finally gotten round to reading the initial article, and the response by sociologists.

Much of the response, including the above, is way over the top. The reviews by sociologists are well written, but based on poor readings. For example, the problem with the review above is the author thinks "Too Much Sociology" is a critical sociology review of critical sociology, when it is in fact a critical sociology review of cultural sociology. Read this part again:

"With the generalization of cultural sociology, however, the critical impact has vanished. Sociology has ceased to be demystifying because it has become the way everyone thinks."

And now go read the entire essay again.

None of your arguments above are relevant with a proper reading of the article. Not saying I agree with the article, but you are here arguing not with it, but an image in your head.

A Social Critique Without Social Science » Cyborgology — November 11, 2013

[…] and observation? Or has Munroe slipped into the same kind of privileged and myopic vision of society that N+1 editors periodically fall into? A perspective that projects one’s own wit and cutting criticism onto the […]