Digital dualism is pervasive, and the understandings that it informs—of ourselves, of our experiences, and of our very world—are a mess. Perhaps this can be chalked up to the fact that digital dualism arises from varying sets of flawed assumptions, and was never purposefully assembled as such by the people who embrace it. But guess what? As theorists, we have the opportunity not only to build new frameworks for understanding, but also to assemble those frameworks with both consciousness and intentionality. So with that in mind, what should a theory of augmented reality look like? What would we do differently from digital dualists?

Digital dualism is pervasive, and the understandings that it informs—of ourselves, of our experiences, and of our very world—are a mess. Perhaps this can be chalked up to the fact that digital dualism arises from varying sets of flawed assumptions, and was never purposefully assembled as such by the people who embrace it. But guess what? As theorists, we have the opportunity not only to build new frameworks for understanding, but also to assemble those frameworks with both consciousness and intentionality. So with that in mind, what should a theory of augmented reality look like? What would we do differently from digital dualists?

It is of paramount importance that theories of augmented reality acknowledge complexities and differences—whether between materials, media, degrees of access, or subjective experiences—without falling into dualisms. Toward this end, I’ve spent the past few weeks engaged in an activity somewhere between “essay writing” and “a thought experiment” geared around pushing my fellow augmented reality theorists and digital dualism critics (especially, but not exclusively) to strengthen our collective work through clarifying both our language and our theoretical frameworks. In Part I, I identified the three major dualisms of digital dualism: Atoms/Bits, Physical/Digital, and Offline/Online. In Part II, I broke all three dualisms apart to argue that none of them are zero-sum, and that furthermore, none of the six terms involved are interchangeable. But saying how a bunch of terms aren’t related is one thing; saying how they are related is another. In this third and final installment, I offer a rough draft of one way we might start to reorganize these terms within an augmented reality framework.

First, let’s get some objectives (alt: “lofty aspirations”) on the table. My thoughts include the following: As a theoretical framework, augmented reality must simultaneously reject binaries yet also articulate connections. It must reject strictly bounded categories generally, and it must recognize that both categories and terminologies are always historically and culturally contingent. It must emphasize that societies and technologies are co-produced, that technologies are not neutral, and that neither the meanings nor the impacts of technologies are intrinsically determined. It must account for complex differences between individuals’ experiences without resorting either to hierarchical ordering or implicit valuation, whether of the experiences themselves or of the people who have them. And it must do all of these things without erasing, ignoring, or neglecting critical issues of power and inequality.

No small task, so good thing this is a collective enterprise.

Over the past month or so, I’ve been thinking about whether intersectionality might not have something useful to teach us here. The term was initially coined by Kimberle Crenshaw [pdf] and then elaborated by Patricia Hill Collins, both of whom I highly recommend reading directly if you haven’t already. For the purposes of this post, however, I’ll offer a very (very) simplified synopsis: People like to think about stuff in binary terms, and they virtually never do this in a way that presumes two equal categories; rather, one category is privileged while the other category is denigrated (or “othered”). As much as people like thinking in binaries, however, they don’t tend to like thinking about more than one binary at a time. This is problematic just in general, but it is especially problematic when we start talking about identities and experiences of oppression.

For instance: consider the 1976 court case that led Crenshaw to begin theorizing intersectionality [pdf], Degraffenreid v. General Motors. The gist here is that General Motors had been hiring white women to work in administrative positions, and hiring Black men to work in industrial positions, but not hiring Black women at all. A group of Black women sued General Motors under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, alleging that they had been discriminated against on the basis of race and gender—which seems like a no-brainer, right? But incredibly, they lost the case: the US District Court found that, because General Motors had hired (white) women, the company wasn’t discriminating on the basis of gender, and that because General Motors had hired Black people (who were men), the company wasn’t discriminating on the basis of race. This might be one of the Top Ten Most Facepalm-Worthy Rulings of the last 50 years, but that’s seriously how it played out: the court simply refused to wrap its collective head around the fact that neither “women” nor “Black people” is a uniform group with uniform experiences.

Clearly, a new approach to thinking about identity categories—one that could actually handle the complexity of our social world—was in order.

Intersectionality starts by saying that, yes, people tend to think in binaries, and that yes, such binary thinking does have real effects in the world—but intersectionality also states loudly and clearly that boxing people up into binary categories is a gross oversimplification of reality. The experiences of all women, for example, are not interchangeable; moreover, the category “women” is neither determined nor strictly bounded in the first place. The same goes for categories based on race, class, sexual orientation, or type of embodiment (etc.). If we want to understand people’s lived experiences, the best way to go about that is a) to ask them, and then b) not to assume that those people speak for everyone who happens to share membership in one (or even several) of their demographic groups. To use myself as an example: I may be a white cisgender woman, but if you want to know about my experience of being in the world, Ann Coulter (for instance) is probably not the best person to ask.

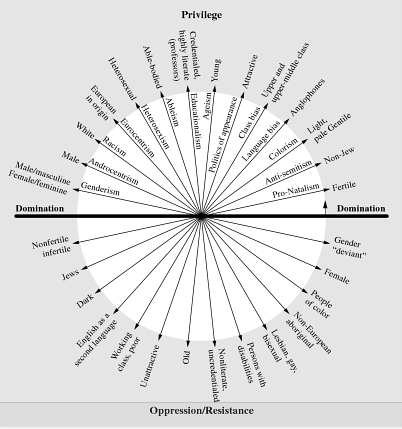

If we can’t understand people’s experiences based on oversimplified binary categories, then what? Intersectionality takes identity variables (such as race, class, sex, gender, embodiment, ability, sexual orientation, and nationality) and treats them not as determined, oppositional binary categories, but as intersecting axes of oppression. These axes of oppression form what Collins calls a matrix of domination, which people both experience and resist at three different levels: the personal level, the community level, and the institutional level. Importantly, intersectionality also rejects hierarchies: “white” is not any better than “not white” just because “white” is privileged along an axis of racial oppression, and oppressions are not additive. To use me again, I’m neither more oppressed than a cisgender white woman rolling in money, nor less oppressed than a transgender Black woman who is homeless; rather, all three of us have different experiences of both privilege and oppression in different contexts. This doesn’t give me the right to think that my experiences of oppression are central or most important—because holy crap, they are not—but critically, it does preempt any debates about which forms of oppression are primary to, or more important than, others. Intersectionality is called what it is for a reason: it refocuses attention from predefined groups (and all the problems with hierarchies and boundaries that those bring with them) to specific intersections of interlocking oppression.

So what’s all this got to do with avoiding or combating digital dualism? Hopefully it doesn’t need to be said, but no: I am not arguing that digital dualism is exactly the same thing as racism or sexism, or even that it’s equally harmful (though I will take this moment to restate that digital dualism often operates in the service of camouflaging or dismissing racism, sexism, and other *-isms when they manifest in digitally-mediated interaction). One theoretical framework to another, however, intersectionality has a lot to teach augmented reality. Intersectionality does a great job of handling complexity, of rejecting binaries, of recognizing differences within broad categories, of accounting for interrelationships, of valuing varying subjective experiences, of keeping an eye on both power and resistance, and of doing exactly what I argue we must do with augmented reality: acknowledge and highlight differences without falling into dualisms.

The question is what an intersectionality-inspired framing of augmented reality would look like. If we use intersectionality’s structural framework to order the concepts associated with augmented reality (and digital dualism critique), what goes where? We’ve got three subtypes of digital dualism identified; might it make sense to think of each occurring on a different level—say the ontological, the experiential, and the moral—the way Collins thinks of people’s experiences of and resistance to domination on the personal, community, and institutional levels? What would happen if we think about people’s experiences of differently mediated interaction not as “more or less real,” but as occurring at the intersections of different affordances? What about conceptualizing presence at the intersections of different awarenesses—eg, I am not “absent,” I am in this moment present at the intersection of a physically co-present party, an SMS-mediated conversation, and ten seconds of a show shared through Snapchat? What other ways are there to build out augmented reality as an analytical framework if we use the structure of intersectionality as a starting point? What other analytical frameworks offer useful inspiration?

The question is what an intersectionality-inspired framing of augmented reality would look like. If we use intersectionality’s structural framework to order the concepts associated with augmented reality (and digital dualism critique), what goes where? We’ve got three subtypes of digital dualism identified; might it make sense to think of each occurring on a different level—say the ontological, the experiential, and the moral—the way Collins thinks of people’s experiences of and resistance to domination on the personal, community, and institutional levels? What would happen if we think about people’s experiences of differently mediated interaction not as “more or less real,” but as occurring at the intersections of different affordances? What about conceptualizing presence at the intersections of different awarenesses—eg, I am not “absent,” I am in this moment present at the intersection of a physically co-present party, an SMS-mediated conversation, and ten seconds of a show shared through Snapchat? What other ways are there to build out augmented reality as an analytical framework if we use the structure of intersectionality as a starting point? What other analytical frameworks offer useful inspiration?

I’m particularly interested in the idea of intersecting affordances, especially as might relate to co-affordances (a concept on which I want to elaborate next week); I’m also interested in feedback about the intersectionality/augmented reality combination generally. What do you all think?

Whitney Erin Boesel is on Twitter: she’s @phenatypical.

Under construction image from here; screenshot of MacArthur Maze traffic from Google maps; axes of privilege image from here; “now what” image from here.

Comments 2

QRG — April 5, 2013

Hi

Thanks for explaining your use of intersectionality in relation to this subject.

And I do disagree with its use both in relation to gender and digital dualism. Did Butler use 'intersectionality'? Did Freud? No, because they did not need to 'complicate' or 'expand' the binary into a range of categories - they questioned all forms of categorisation in relation to gender, bodies and psyches.

My problem with 'intersectional' feminists is they don't reject the binary in the end. They still use the terms 'women' and 'men' as if they were real, useful categories. Remember your post on the lack of women in reports of digital dualist debates? Did that reject the binary? No, it just added 'white' to the category of 'men'. It prioritised the binary of men v women over other issues of gender etc.

Also at the top of your post you say 'digital dualism is pervasive'. To make a claim like that I think one would have to do some empirical research, looking at 'ordinary' (not journalists or academics or not just them) people's views and experiences of 'digital dualism'.

I tell you what's 'pervasive' - feminism. But I still don't see how or why feminist politics (for that is what feminism is - politics) are useful to our understandings of how our lives are changed by the growth of digital technologies. I reject digital dualism AND feminism, and that doesn't seem to stop me thinking about our contemporary world clearly.

My question is: apart from Haraway's influence, why does cyborgology need feminism?

Michael Fischer — April 5, 2013

Whitney Boesel presents an interesting and useful contribution that moves the conversation ahead considerably, and I am grateful for the references to intersectionality, some of which I was unaware. This is an excellent continuation of G. P. Murdock presentation in his 1971 Huxley Lecture to the Royal Anthropological Institute when he proclaimed that anthropologists and other social scientists had to abandon ‘organic’ approaches and recongnise that Culture and Social Structure existed as outcomes of the aggregate activity of individual people, not as drivers per se, or in the terms developed by Dwight Read and myself in the 1980s and 90s, as instantiations of more fundamental agent-centred relationships. The arguement does not go far enough, however. Categories such as ‘women’, ‘blacks’, ‘Ph.D. students’ and so on are emergent properties of people, not fundamental properties. It is not so much that people are embedded in different classificatory groups, but rather that a number of classificatory groups can be evoked based on a perspectual viewpoint of the productions of aggregates of people. Many different sets of categorial groups can be composed from a given aggregate of people, but the formation principles are based on properties of the individuals, not the groups. Such groups are social inventions, not social productions. So whereas, for example, modern ethnic studies often depict people as manipulating, negotiating or managing their different group identities in their navigation through life situations, it might make more sense to see this as people manipulating, negotiating or managing inter-group dynamics through their instantiating one group over another in different circumstances. Gender equality or ethnic equality made strides when these were mobilised in corporate groups rather than categorial groups. The ‘other’ as a categorial group can be disregarded; as a corporate group they must be confronted or consolidated.

Boesel argues convincingly that a focus on intersectional loci obviates the need for a ‘digital divide’. But likewise this obviates the need for ‘augmentation’ as well, unless one is going to press this into service for the whole of human evolution. There is some value in referring to the introduction of new knowledge and tools as an augmentation, in the sense that these new introductions introduce new opportunities for people and thus expand, or at least modify, their agency, and thus change the dynamics of what can be instantiated in the world. Thus we might find value in discussing the ‘digital augmentation’. But there is no need for a subsequent ‘augmented reality’ except in the weakest sense of the term. Although taking note of an important human capacity, invention, augmentation does not in itself take us closer to understanding the how intersectionality contributes to shaping dynamic human processes and productions.

This is what Applin and I have been examining over the past few years in looking at the impact of ‘digital’ and ‘mobile’ augmentations based on a framework comprised of polysocial networks; the abstract networks representing the union of all instantiable networks for each person in an aggregate; and the instantiation of a subset of these in a given context, which we have called PolySocial Reality. In terms of intersectionality, each person represents a perspectual intersection of many potential resources for information and interaction, only some of which can be instantiated in a given instance, considering constraints of time, cognitive capacity, and mutual exclusion. In past augmentations the changes in polysocial networks and the exercise of agency in instantiating these in different contexts have eventually been resolved in widespread practices that become regarded as ‘cultural’. The ‘digital’ and ‘mobile’ augmentations have yet to be so consolidated, although recognisable forms are emerging albeit with strong divisions by age and other factors influencing life experience.

Thanks again for a thought provoking piece.