Gun ownership and the decision to carry a gun in public may seem like an individual choice. However, in a recent Vox podcast, sociologist Jennifer Carlson explains that carrying a gun in public is intertwined with cultural understandings of gender, race, and family. Carlson interviewed dozens of gun carriers and NRA instructors. She even went through the training herself, received her license to carry, and became a certified instructor to understand the culture of individuals who regularly carry guns.

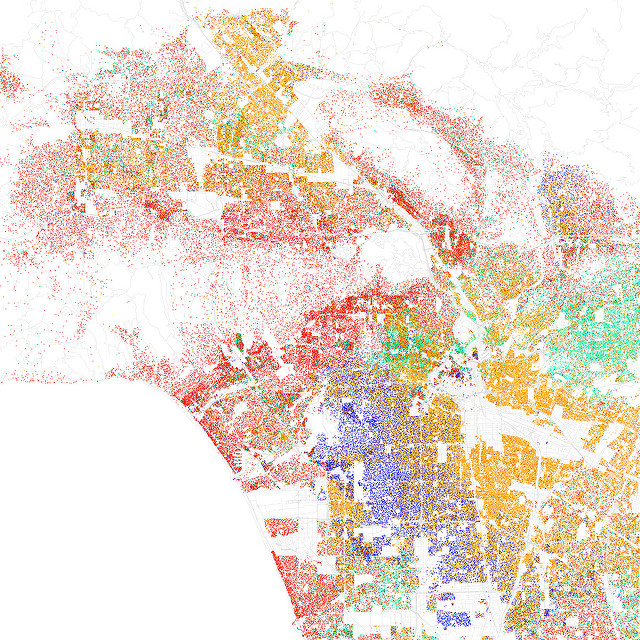

Regarding race, NRA courses often neglect lessons about the impacts of racial bias in determining who may be a threat, for example. In terms of gender, Carlson finds that men — who carry firearms more often than women– are influenced by feelings of a loss of masculinity, socioeconomic decline, family histories, and ideas around civic responsibility.

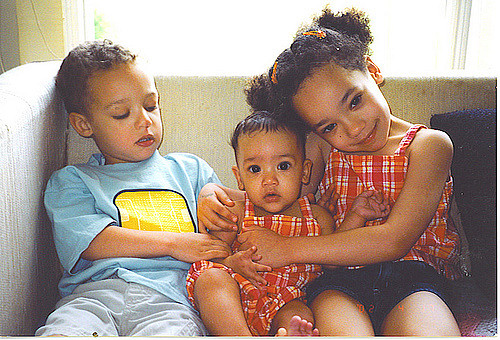

“When I talked to [women] I got a very different narrative [than men] about why they are carrying guns… If we [go] back to the Second Amendment debate, it’s often ‘This is my individual right,’ ‘This is about my individual right to self-defense,’ or ‘It’s about self-protection.’ And when I talked to men…oftentimes it was about self-defense but it also was about family protection — family protection was a huge piece of the puzzle. This idea, if I’m working a job at night, and my wife is at home and she’s alone, there needs to be a firearm there so that she can be protected. And that’s a really interesting move because that’s [about an] absent male protector, [whereas] women were individualistic in terms of ‘This is my right to self-defense,’ ‘My life is valuable in and of itself,’ and ‘I can have a gun to protect myself.’

In other words, both men and women valued owning firearms for protection, but women framed their gun ownership in terms of self-protection, while men viewed gun ownership as a way to protect others.