The Changing Lenses project, as a conversation between a photographer and a sociologist, is very much based in the interaction of images and stereotypes, assumptions and visions, contexts and the understandings of those contexts.

Trayvon Martin was killed in late February 2012, and the case against his shooter, George Zimmerman, continues. So, too, do public reactions to Martin’s death and Zimmerman’s defense. Perhaps no combination of image and stereotype was more prominent or controversial in American culture this past spring than hoodies and race. For a sociological perspective and relevant research on the controversy and media coverage of it, we can recommend Jeff Dowd’s rich post on our TSP Community Page Sociology Lens, “Disembodied Racism and the Search for Racist Intent.”

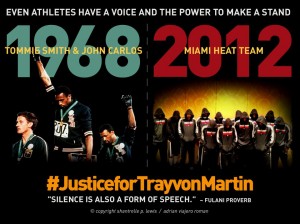

For our part, our conversations have taken us in two directions. First, informed by interests in sport, race, and politics, Doug Hartmann found himself ruminating on the photo of LeBron James and the Miami Heat posing, heads down as if in silent reflection, in hoodies. The moodily lit image prompted thoughts about social consciousness and the political voice of athletes in America (more on this recently), thoughts on Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s Olympic victory stand demonstration back in 1968. Both incidents share the fact that athletes’ may most effectively make political expressions through their bodies and actions—ironically, not a point Hartmann got into in his TSP White Paper with Kyle Green, “Sport and Politics: Strange, Secret Bedfellows.”

Second, Wing Young Huie set out to consider hoodies as one symbol of “otherness” and breaking down stereotype. Since March, he has undertaken a project called “We Are the Other,” which includes the diptych above, Roland.

Perhaps these two approaches don’t come together, but when you read reactions to both Martin’s death and the case that has unfolded in the media and in the public consciousness, as covered in our TSP Roundtable “Thinking about Trayvon: Privileged Response and Media Discourse,” more questions than answers will necessarily be raised. In that Roundtable, for instance, sociologist Enid Logan raised the idea that perhaps protestors should have been holding signs reading “I am George Zimmerman,” as it “would have implied a truer, more honest understanding of the relations of power, privilege, and economic and social violence that contribute to the devaluation of black life.” Or maybe, as fall comes on, we’ll all just raise our hoodies against the cold and take a moment to consider how symbolic this clothing has become.

Comments 1

Sarah Van Valkenburg — December 13, 2012

I think that this type of "otherness" dispay while powerful, could be considered different things depending on where a person lives. If a person lives in a poverty stricken area where crime is commonplace, it could be taken as an act of defiance and get them more singled out by the police for punishment. In Punished, by Victor Rios, he was a PhD student that dressed like the kids that he shadowed in Oakland, and was regularly stopped and quesitoned by the police along with the boys. The police assumed that just because he dressed and looked a cerain way that that he fit a certain sterotype. The hoods statement could be connected to this becuase a person could be singling themselves out to be thought of as suspicious by wearing a hood if they lived in a place like Oakland where the police are always stopping people. Now, if a person tried the same thing in a different neighborhood, the outcome may not be the same. Also, if a person of a different race was wearing a hood, I doubt the same thing would happen either. For example, if I were to wear a hood in my neighborhood, it would not be thought of as an act of defiance or a statement, everyone would just think I am cold. That just goes to show how racial thinking still exists in our world today, even if people refuse to believe it.