On April 24, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services rang the death knell on work authorization for spouses of high-skilled immigrant workers. Under the direction of the White House, the USCIS conducted an audit of the H-1B guest worker program, specifically to see if it complies with the President’s Buy American, Hire American executive order. In a report submitted to the Senate Judiciary Committee, the director of the USCIS proposed sweeping changes to the program, including removing regulations that would allow the spouses of H-1B workers to obtain work permits.

Despite being an established program for almost thirty years, the H-1B program has become a target for the current administration. The H-1B visa program first came into existence after the passage of the 1990 Immigration Act. As the tech boom of the 1990s and rising fears about “Y2K” created a demand for technically-trained labor, U.S. companies began to seek workers from around the world. The H-1B is given to workers in “specialized and complex” jobs. Typically issued for three to six years, the visa allows employers to hire foreign workers.

While the visa has always been classified as a “temporary nonimmigrant visa,” employers can sponsor the visa holders for permanent residency. The program also created the H-4 family reunification visa, which go overwhelmingly to the women spouses of workers. Children under the age of 21 years are also eligible for the H-4 visa.

The H-4 visa has real benefits for foreign workers, as it allows hundreds of thousands of family members to migrate to the U.S. along with the primary visa holder. Employers have supported the H-1B and H-4 visa, arguing that companies can bring the “best and brightest” to work in the U.S., particularly if they can also bring their families along. However, the visa also comes with restrictions: H-4 visa holders can’t work legally, apply for a social security number, or qualify for many federal education programs.

In my ethnographic study of H-1B and H-4 visa holders, I document the long-lasting negative impacts of these work restrictions on women’s careers, emotional health, and economic well-being. Many spouses of H-1B workers are also well educated and have advanced degrees, but after moving to the U.S., they become housewives. Their dependency creates other problems as well. In cases of domestic violence, H-4 visa holders have difficult leaving their partners without putting their own visas at risk.

There has been some relief for H-4 spouses who were already in the process of applying for their green cards. In 2015, the Obama administration issued an executive order that allowed H-4 visa holders employment authorization. But that authorization is contingent on the good standing of the primary H-1B visa holder. In other words, if their partner loses the H-1B, the spouse also loses her work authorization.

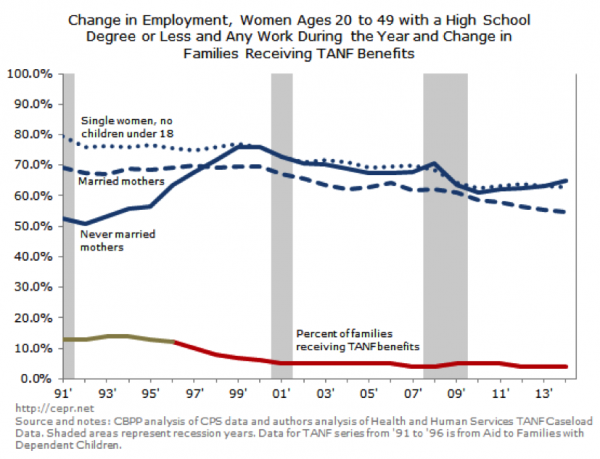

Even with this risk, the ability to work has provided welcome respite for tens of thousands of dependent spouses. After spending years stuck at home, the chance to join the workforce is important both psychologically and economically vital. As my study and recent reports have shown, many families delay making major life choices or even having children until both partners are able to work. Having two incomes also offsets the high cost of living in regions where H-1B workers are concentrated. In addition, women’s participation in the workforce can translate into greater gender equity at home.

However, with this most recent report by the USCIS, we not only see a mandate to severely curtail the number of H-1B visas granted, but also to eliminate rights for their family members. As my research has shown, when immigrant women are given opportunities to become economically productive, they are more likely to stay in the U.S., and receive numerous other benefits. Ending the ability of immigrant spouses to work will undoubtedly reduce the amount of highly skilled workers willing to move to and stay in the U.S.

Amy Bhatt is an Associate Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies at University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Contact her at abhatt@umbc.edu.