Sociologist and Associate Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Jessica is an award-winning teacher, a leading expert on inequalities in family life and education, and the author of the forthcoming book Holding it Together: How Women Became America’s Social Safety Net (Portfolio/Penguin, 2024). Her previous books include Qualitative Literacy: A Guide to Evaluating Ethnographic and Interview Research (with Mario Small; University of California Press, 2022), Negotiating Opportunities: How the Middle Class Secures Advantages in School (Oxford University Press, 2018), and A Field Guide to Grad School: Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum (Princeton University Press, 2020).

Jessica has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Atlantic, and CNN. She also blogs at ParenthoodPhD and is a mom of two young kids.

Here, I ask her about her new book, Holding it Together: How Women became America’s Safety Net, which is out now from Portfolio. You can find out more about Jessica at her at website. And you can follow her on Twitter @JessicaCalarco

AMW: How do we groom girls to stand in for the social safety net and when does that grooming start?

JC: Other high-income countries have invested in social safety nets to help people manage risk. They use taxes and regulations, especially on wealthy people and corporations, to protect people from falling into poverty, give people a leg up in reaching economic opportunities, and ensure that people have time and energy to help take care of their communities, their families, their homes, and even themselves.

In the US, we’ve tried to DIY society. We’ve kept taxes low, slashed huge holes in the meager safety net we do have, and we’ve told people that if they just make “good choices,” they shouldn’t need a safety net at all.

The problem, of course, is that we can’t actually DIY society. Forcing people to manage all that risk on their own has left many American families and communities teetering on the edge of collapse.

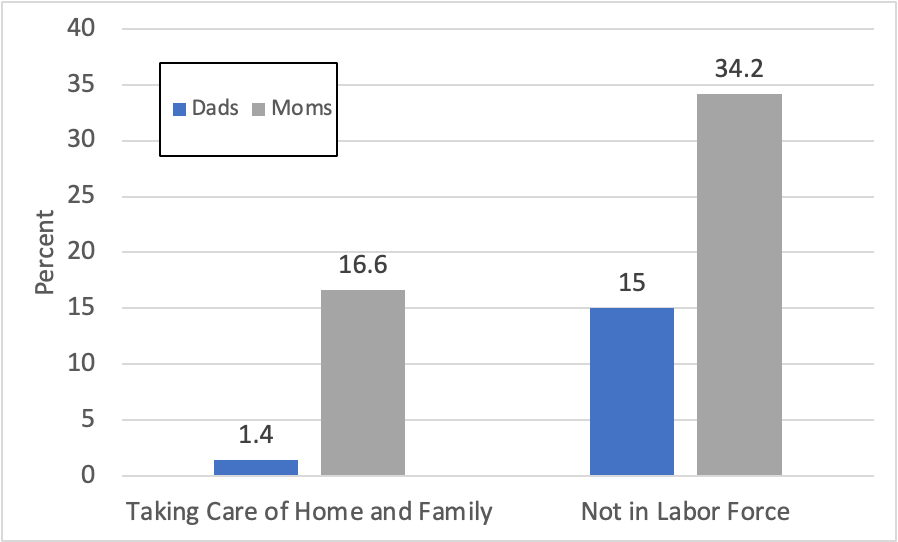

And yet, we haven’t collapsed because women are holding it together, filling in the gaps in our economy and the gaps in our threadbare safety net. In the US, women are disproportionately the default caregivers for children and for the sick and elderly and destitute. They’re also the ones who disproportionately fill the lowest-paid jobs in our economy—jobs in essential service sectors that are too labor-intensive to be both profitable and broadly accessible, including jobs in childcare and home health care.

As I show in Holding It Together, women’s unpaid and underpaid labor helps maintain the illusion of a DIY society by making it seem as though we can get by without a net. And American culture grooms, guilts, and gaslights them into fill those gaps.

From the time girls are old enough to hold a babydoll, they’re taught to see themselves as helpers and treated by adults as mothers-to-be. Young girls are tasked with caring for their siblings, cleaning up around the house and the classroom, and even being teachers’ assistants and keeping their peers on track at school.

This early socialization grooms girls to stand in for the social safety net. It leads many girls and women to see themselves as “naturally” suited for caregiving and thus to accept both paid and unpaid caregiving roles. At the same time, and even if girls are skeptical of the idea of “naturally” gendered caregiving proclivities, their early experiences with caregiving also teach them that if they don’t do this work or do it well enough, there’s a good chance that no one else will. Which means that the choice not to step in and fill those gaps means letting down their family members, friends, and communities, who, in the context of a DIY society, may have nowhere else to turn for support. Which is part of why women in the US experience a disproportionate amount of guilt.

Meanwhile, a lack of similar socialization for boys grooms them to buy into the idea that caregiving is women’s work. That belief, as we saw on full display with NFL kicker Harrison Butker’s recent graduation speech, then allows boys and men to exploit the labor of girls and women without any feelings of guilt. Put differently, those beliefs allow boys and men to see themselves as “good guys” even if they do little or none of the work of care.

AMW: What is the Supermom myth?

JC: The Supermom myth is one of a set of myths that I talk about in the book—myths that operate to delude Americans into believing that we can get by without a decent social safety net and to divide us by race, class, gender, religion, politics, and other life circumstances in ways that keep us from coming together to demand the kind of net that would better support us all.

The Supermom myth, in particular, is the idea that American children are under threat and that only their mothers can protect them from harm. As I show in the book, many Americans believe this idea, at least in part, because of fear-mongering efforts intended to persuade them to think that way. And believing that myth operates to create the perception that we don’t need a social safety net, because mothers are the only ones capable of keeping their children safe.

Take, for example, the Satanic Panic around childcare in the 1980s/90s. Conservative pundits and policymakers used wildly inaccurate allegations against childcare providers to stoke parents’ fears and create the perception that children are only safe at home. In light of those fears, and despite clear evidence of the benefits of communal care for both children and parents, many families pulled their children out of childcare centers or tried to avoid enrolling them if they could. And that pullback on trust in formal childcare also helped stemmed the tide on maternal employment, which had been increasing for decades and suddenly stalled.

This fear of childcare has also persisted and continued to drive down maternal employment and drive up the guilt that American mothers feel when they engage in paid work. In a representative survey of more than 2,000 parents of children under 18 from across the US, I found that almost half (47 percent) of parents believe that it’s best for children if their mothers stay home and don’t work for pay. As I show in the book, those beliefs are attractive to women, particularly if their paid work opportunities are limited, or if they struggle to find the affordable childcare they would need to engage in full-time paid work, because being the Supermom offers them a way to feel that their work is valuable, even it isn’t highly paid or paid at all. At the same time, those beliefs also discourage mothers from fighting for a stronger social safety net, because, despite the toll this work takes on them, they’ve made doing the work of holding it together the source of their self-esteem.

In the book, I also extend these analyses to include newer fears around childhood, including the panics around Critical Race Theory and transgender kids. And I show how conservative Christian mom-fluencers are stoking these fears and using them to undermine trust in schools and other government institutions while also promoting the “tradwife” trend.

AMW: What would a better net mean?

JC: A better social safety net would use taxes and regulations, especially on wealthy people and corporations, to protect people from poverty, give people a leg up in reaching economic opportunities, and ensure that people have the time, energy, and incentive help take care of their communities, their families, their homes, and even themselves. As we saw with relief programs put in place during the Covid-19 pandemic—which included everything from student loan moratoriums to child tax credits and stimulus checks to rent relief and universal free school lunches—supporting people can dramatically improve their lives.

In practice, a better net would strengthen the formal care system and make it more possible for families to outsource the help they need with caregiving through programs like free universal healthcare, eldercare, childcare, and education from early childhood through post-secondary school. Ideally, those programs would also be funded not only to a high level of quality but also to the level of sustainability—ensuring that caregivers are cared for, as well. At the same time, a better net would also strengthen the informal care system, allowing people to contribute more equitably to a shared project of unpaid caregiving by guaranteeing them universal paid family leave, ample paid vacation time, limits on paid work hours, and stipends for families with dependent-care responsibilities. And finally, a better net would also allow all people to live with dignity, regardless of their choices or their circumstances. It would raise the minimum wage, increase protections for paid workers and their unionizing efforts, ensure access to affordable food, housing, communication, transportation, and other basic necessities, and eliminate the punitive checks on “deservingness” we have built into the meager safety net we currently have.

We got close to building key parts of this net with Build Back Better. And there’s no reason we couldn’t try again.

Alicia M. Walker is Associate Professor of Sociology at Missouri State University. She is the current editor of the Council of Contemporary Families blog. Follow her on Twitter at @AliciaMWalker1.