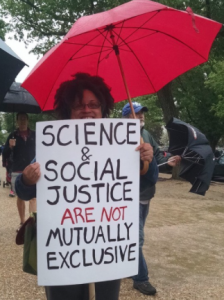

Scientists stepped out of their offices and labs to make a statement. On Saturday, April 22, the March for Science took place in Washington, D.C. along with over 600 satellite marches. With funding and facts under threat by the new administration, scientists from a wide range of disciplines and supporters of science filled the streets to advocate for the importance of scientific research and evidence. To get a better understanding of the significance of the March for Science and the threat of the current administration’s proposed policies, we spoke to Dr. Philip Cohen who marched in D.C. on Saturday. Cohen is a professor of Sociology at the University of Maryland and a senior scholar at Council on Contemporary Families. What did we learn? The March for Science is positive, but there is more to be done.

Q: What kind of impact (if any) do you think the March for Science could have on policy and public opinion?

PNC: We are at an amazing moment when the forces against science and reason and the public appreciation of science both seem to be peaking, which implies a heightened state of conflict. Like the Women’s March and the protests against Trump’s immigration and tax policies, I hope the March for Science helps to coalesce the movement against Trumpism and build solidarity for the long difficult times to come. Whether it will yield tangible policy results in the short run I have no idea.

Q: The American Sociology Association and other social science groups endorsed the March for Science. What do you think such groups are hoping to gain from their participation in the march? What would you like to see as a result of the March?

PNC: In addition to ASA, I was glad to see the Population Association of America, to which I also belong, sign on to the March. We have immediate concerns, especially around support for social science research through NSF, NIH, and other agencies — and also the federal data collection agencies, principally the Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Center for Health Statistics, National Center for Education Statistics, and others. Even without aggressive manipulation of their work, or opposition to their specific projects, just the budget slashing they’re talking about could be extremely bad. On the plus side, those agencies employ a lot of people, and their work has direct applications in all Congressional districts and for a lot of important constituencies, so I’m optimistic that mobilizing support for government data might yield positive results at the federal level. And the professional associations, including ASA and PAA, can play an important role in that. But it’s too early to tell.

Q: The new administration has shown that science programs are not a priority for them. More specific to social sciences, the National Endowment for the Humanities is on the chopping block in the administration’s proposed budget. What effect does this have on your research and others like you, and what would you recommend those who oppose such cuts do after the March for Science?

PNC: For social scientists, NSF and NIH are the most important agencies. Other research is funded by smaller agencies like NEH, and also by research divisions in other agencies, such as the Department of Defense, Environmental Protection Agency, and so on. Anyone whose research is federally funded right now has to be very concerned and thinking about alternative avenues for funding. Some philanthropic agencies will step in, but they can’t replace the big federal budgets.

One key area I’ve been very involved in, which is directly relevant here, is the open scholarship movement. This was already important, but with the assault on science and reason, and the potential slashing of research budgets, it’s even more vital to make our research more efficient, to reach more people more quickly, to maximize the potential for collaboration and information sharing — all the outcomes we hope to achieve through open scholarship. That’s why I’ve been involved in the SocArXiv project, which seeks to drive social science toward openness. American academia wastes billions of dollars propping up an exclusionary publishing system that is slow, inefficient, and deleterious to the cause of science and knowledge creation. We can do better with less, and now is the time to make that happen. I hope social scientists, in particular, will take the simple steps necessary to make their research freely available, which can be an important piece of building public support and trust in our efforts.

Megan Peterson is a senior sociology major at Framingham State University and a Council on Contemporary Families Public Affairs and Social Media Intern.