This briefing paper, prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families, was originally released on January 16, 2019.

Although many sexist prejudices have weakened over time, gender stereotypes still influence employers’ decisions during the hiring process, and those stereotypes disadvantage both women and men. In a forthcoming article in Social Forces, I show that employers continue to assume that men and women have “naturally” different skills and preferences that make members of each sex better or less suited for different types of jobs. They associate men with physical prowess, leadership, mechanical aptitude, and competitiveness, whereas they associate women with nurturance and “people skills” such as tact, patience, cooperation and communication. Women are assumed to be less capable or interested in the first set of qualities and men are assumed to be less capable or interested in the second set.

We have long known that sexist stereotypes hurt women’s hiring prospects in the labor market, but my research shows that it hurts some women more than others and that it also hurts men. I find that employers tend to discriminate against female and male applicants when either applies for a job typically associated with the other sex. Think of a woman applying to a manufacturing job, or a man applying to an administrative support position. Surprisingly, however, I found no discrimination against women in the early hiring phases when they applied for male-dominated middle-class jobs, at least in the mid-status, entry-level positions that I tested. By contrast, working-class women applying for traditionally male-dominated working-class jobs faced significant discrimination, while men applying for jobs that have traditionally been staffed by women faced discrimination in both working-class and middle-class contexts.

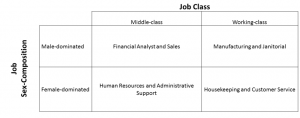

Using a field experiment, I submitted fictitious male and female resumes to openings for more than 3,000 jobs. Specifically, I sent resumes for male-dominated and female-dominated jobs in both middle-class and working-class occupations, as indicated in the chart below. The middle-class jobs were entry-level, required a bachelor’s degree, and paid well above minimum wage but well below high-paying professions. The working-class jobs paid minimum wage or higher and had few educational requirements. In each class of jobs, the average pay rate varied by gender, with jobs that mainly employ men typically paying more than the jobs that mainly employ women.

Each job opening received one male resume and one female resume. The male and female resumes were comparable in education, skill, and work experience. I then recorded the callbacks that the male and female applicants received from real employers for a job interview.

Discrimination against Female Applicants

My findings show that employers discriminated against female applicants for working-class jobs primarily occupied by men. For example, in manufacturing and janitorial positions, male applicants were 44 percent more likely than equally qualified female applicants to receive a callback from employers. Discrimination was particularly pronounced when male-dominated working-class jobs also emphasized masculine attributes in their job ads, such as requiring job seekers to demonstrate physical strength or mechanical aptitude. In these cases, male applicants’ probability of a callback for an interview was double that of female applicants (.10 versus .05).

By contrast, I found no discrimination against female applicants during the early hiring process in middle-class male-dominated jobs, likely because these jobs stress attributes, such as general cognitive ability, that have become less exclusively associated with men. As late as the 1960s, most Americans did not view women and men as equally capable of rationality and critical-thinking. This seems to be one area in which sexist prejudices have been greatly reduced, to the benefit of women seeking entry into jobs that require educational credentials. In contrast, masculine cultures in working-class employment continue to stress attributes that are stereotypically linked to men, such as mechanical aptitude or physical strength. This is true even when few real differences exist in requirements. For example, female applicants faced hiring discrimination in janitorial work even though a female-dominated working-class job such as a house cleaner often requires similar strength and stamina.

Despite the fact that women of all education levels have incentives to enter male-dominated jobs because they pay significantly more than comparable female-dominated jobs, only women with bachelor degrees or higher have done so in significant numbers. The fact that working-class employers exclude women from initial job-candidate pools might help explain why many working-class jobs remain as segregated today as they were in the 1950s.

Discrimination Against Male Applicants

Male applicants also faced discrimination during the hiring process due to sexist gender stereotypes surrounding men’s fit with female-oriented work, and in this case, discrimination occurred in both working-class and middle-class occupations during early hiring processes. I found that regardless of the occupational class or educational requirements of a job, employers were significantly less likely to extend an interview invitation to a male applicant compared to a female applicant for a job in a female-dominated occupation. Female applicants were 52 percent and 21 percent more likely than male applicants to receive a callback in middle-class and working-class contexts, respectively. So, in contrast to my findings about women, discrimination against men entering female-dominant occupations was highest in middle-class jobs.

Male applicants were particularly disadvantaged when a job was both female-dominated and the job ad emphasized feminine attributes. For example, when a middle-class female-dominated job emphasized supposedly feminine attributes, such as friendliness and good communication skills, in the job ads, a female applicant was almost twice as likely as the male applicant to receive a callback (.10 versus .06).

One possible reason for this discrimination is that “women’s work” is generally considered beneath men, suggesting that there might be something “wrong” with a man who wants to do it, or raising suspicion that the man would leave as soon as he got a better, more “masculine” job. Indeed, research shows that men in female-dominated jobs have a higher turnover rate, tending to leave soon after their entry.

Alternatively, employers may assume (or fear that customers will assume) that the stereotypes associated with masculinity will make a man less competent at the work and that he will be less patient, less tactful, less nurturing, and so forth.

Sexism thus limits men’s career choices as well as women’s. Although restricting men’s entry into female-dominated jobs, which are typically lower–paying, is less costly than barring women from typically higher-paying male-dominated jobs, such discrimination could be increasingly problematic for men, since industries dominated by women, such as service and healthcare, are projected to add the most jobs in the future.

Still, it does not follow that men are now more disadvantaged by sexism than women. For one thing, once men do gain entry to female-dominated jobs, they continue to earn higher wages than similarly qualified women, and in some cases are actually promoted more quickly. So while men may struggle to get an interview, these disadvantages often quickly dissipate (particularly for White men) if they land a job in a female-dominated field.

Second, it is important to note that although women have had success entering middle-level jobs that were traditionally occupied by men, they have had limited success entering or being promoted equally in elite male-dominated jobs. Coupled with my findings about discrimination against women entering male-dominated working-class jobs, this suggests that women are still discriminated against in work thought to require any of the physical OR mental prowess, leadership, and status traditionally associated with men.

Conclusion

In conclusion, gender stereotypes and biases during the hiring process limit both men’s and women’s career options. For women applying to male-dominated jobs, hiring inequality seems to be most pronounced at both the bottom of the occupational hierarchy and at the very top, where rewards are exceptionally high. For men applying to female-dominated jobs, hiring inequality exists across the occupational structure. Although this discrimination is less costly than the kind experienced by women, it may hamper working-class men in particular from adjusting to the changing occupational structure of America, as blue-collar jobs continue to shrink. And until we stop prejudging people’s interests and capacities on the basis of sexist stereotypes, we will continue to steer men and women into different and unequal jobs, denying them the opportunity to develop a well-rounded combination of human, as opposed to gender-specific, capacities.

By Jill Yavorsky, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Organizational Science, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, jyavorsk@uncc.edu. CCF advisory available here.

Will Meghan Markle be welcomed in the royal family? The recent wedding of Markle, a biracial woman of Black and White heritage, and Prince Harry, a White male member of the British royal family, marks a social milestone. More than fifty years out from the Supreme court decision that legalized interracial marriages across all 50 states in the U.S., this wedding has inspired a new conversation about racial inclusivity infusing

Will Meghan Markle be welcomed in the royal family? The recent wedding of Markle, a biracial woman of Black and White heritage, and Prince Harry, a White male member of the British royal family, marks a social milestone. More than fifty years out from the Supreme court decision that legalized interracial marriages across all 50 states in the U.S., this wedding has inspired a new conversation about racial inclusivity infusing