A briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families Online Symposium on Gender and Millennials, originally released March 31, 2017.

As Pepin and Cotter’s new work shows, attitudes towards gender equality across different domains have diverged. Although young people hold increasingly egalitarian views about women’s role in the workplace, the increase in their support for egalitarian attitudes about women’s role in the household has stalled and even seems to have slid.

Why the lag? Old masculinity scripts, perhaps. Part of the reason for this divergence may be that changes in the labor force have driven changes in how men view women’s roles at home. As women get closer to equal footing outside of the home, men may be compensating by stressing the importance of traditional women’s roles in the home. In essence, saying that women should be the primary caregivers in the household may be a powerful way for young men to assert their masculinity and for women to assert their support of traditional gender roles in a world in which the dominant economic role of men is no longer a given.

In a 2012 article, Yasemin Besen-Cassino and I showed that men who earned less money than their wives did less housework than those men who earned the same or more than their wives. Interestingly, and in a twist on other research in the same area, we found that this behavior was conditional on total rather than relative income – men were threatened only by high-earning wives, regardless of their own income – and that the reduction occurred in only one type of housework — cleaning. They made up for their cutbacks in cleaning by an increase in cooking, a behavior that has become effectively de-gendered in recent years.

We theorized that this was likely the result of men’s adopting symbolic masculinities in response to a gender role threat: In this case, the threat was the loss of their traditional economic dominance within the household, and the symbolic response was a reduction in the amount of time spent on cleaning. Men who experienced income loss relative to their wives did not cut back on the total time they spent on housework but only in the type of housework most traditionally associated with the feminine role.

Our finding that relative income only mattered when a wife had relatively high earnings may have implications for the recent slippage in support for male breadwinning families noted by Pepin and Cotter. A wife who earns more than her husband only constitutes a threat if she actually earns what is an objectively high amount of money. All of this means that, until recently, direct economic threat to men was limited to a relatively small group. However, as women gain standing in the workplace, and men increasingly view the world as being slanted towards women economically (whether it is or not), that small group has been growing. Of course, high school seniors are unlikely to have been directly threatened by women’s higher earnings, so they may be absorbing the message that male privilege is under assault from media accounts or the experiences of others in their family or community.

Refusing to clean the house is just one way in which men can symbolically express their masculinity in response to earning less money than their spouses: The political and social realms may offer men an even more potent way to display their masculinity to themselves and others, something that we may be seeing in the exit polls analyzed by Kawashima-Ginsberg. In a survey experiment carried out last year, my colleagues at the PublicMind poll and I primed men to think about how, in an increasing number of households, women now earn more money than their husbands. Men who were made to think about this sort of gender threat became dramatically less likely to support Hillary Clinton in a head-to-head match-up with Donald Trump, though no less likely to support Bernie Sanders. This suggests that when men are nudged to think about situations in which they lose traditional economic sources of masculine prestige, they become less willing to accept women’s political leadership, at least from women who embrace non-traditional gender roles.

However, qualitative research shows that that not all men adopt traditionally masculine roles in response to gender role threat. Some men may instead go the other way, creating new masculine roles. For instance, instead of seeking alternative ways to buttress traditional masculinity, they may begin to stress their roles as fathers, or craftsmen, or activists as alternative sources of masculinity. Still others, as Sullivan (2011) has argued, may not feel threat at all.

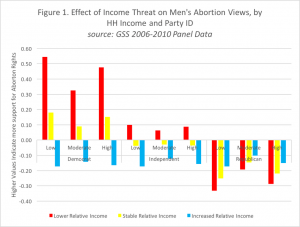

Men’s political views polarize more when it seems like they are losing ground. Men might also be more or less threatened because of their pre-existing social and political outlooks. To examine this, I made use of the 2006-2008-2010 General Social Survey Panel Study, which contacted 2000 Americans up to three times during those years, and looked for changes in men’s political and social views that were associated with changes in their relative earnings within the household. The panel design is ideal for this sort of study, as it means that we’re not looking at whether men support or oppose abortion rights, for instance, but whether they’ve become more or less supportive over the last two years. The period is also perfect for this sort of analysis, given the economic disruptions suffered by many households over the course of the 2008 recession.

I expected that men would feel the greatest gender role threat – and therefore, the greatest need to compensate for it by expressing symbolic masculinities – when they had lost larger amounts of income relative to their spouses. For example, I found that over a period of two years, 10 percent of respondents ended up contributing about 40 percentage points less towards the household income than at the start of the period, dropping, say, from 60 percent of the household income to 20 percent. Such men, I reasoned, were far more likely to feel a great deal of gender role threat arising from their economic status than men who maintained or improved their share of household income over the two-year period. This is slightly different than the sort of threat induced in the survey experiment above (where we primed respondents to think about women getting ahead) – men here were threatened by their loss of earnings, rather than the gains of women, but the type of economic threat to breadwinner status is the same in both cases.

To test the effects of this sort of gender role threat on men’s political and social views, I looked for changes in their views on two issues that have a significant liberal-conservative divide: support for abortion rights and support for government financial aid to African-Americans.

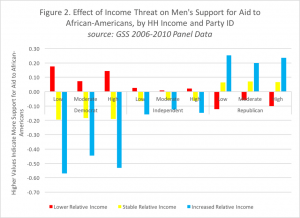

Republican and Democratic men changed in different ways. For one group of respondents, the results confirmed the long-standing belief that men who experience gender role threat become more supportive of traditional ideals and conservative politics. Men who started the period as Republicans but ended up contributing less to their household income compared to their wives at the end of the two years become significantly less supportive of abortion rights over the period. While other Republican men also tended to become less supportive, the decline was largest for men who lost the most income relative to their spouses. (See Figure 1.)

But among Democratic men, the results were strikingly different. Those who lost income relative to their wife over the period became, on average, 0.5 points more supportive of abortion rights. While conservative men came to hold more conservative views on abortion under conditions of economic gender role threat, liberal men come to hold more liberal views.

To add to the complication, Democratic men who gained income relative to their spouses actually became less supportive of abortion. Among liberal men, it seems, those who came to fill the traditional role as a breadwinner became more conservative in their views as well as their economic role in the household.

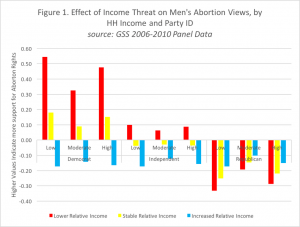

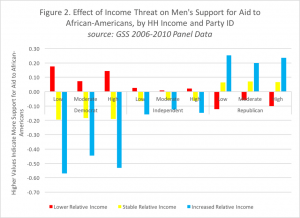

Similar effects hold for views on government aid to African-Americans in the same GSS panel data. The specific question asked respondents whether African-Americans should “work their way up,” rather than receiving “special favors,” an item that has frequently been used to measure support for government aid to African-Americans[1]. In general, Democratic men became a little less supportive of such aid over a two-year period, and Republican men became a little more supportive, a result indicative of expected reversion to the mean. However, men who lost income relative to their spouses moved in a direction different than the rest of their fellow political thinkers. Republican men who lost income became even less supportive of government aid to African-Americans, while Democratic men in this position became even more supportive. (See Figure 2.)

[1] The questions used in the GSS panel survey ask respondents: “Do you agree strongly, agree somewhat, neither agree nor disagree, disagree somewhat, or disagree strongly with the following statement: Irish, Italians, Jewish and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without special favors.” Responses range from “Agree Strongly” (27percent in first year) to “Disagree Strongly” (4 percent in first year), along a 5 point scale, in which higher responses indicate more support for aid to African-Americans, and lower responses indicate less support. Overall, the sample in the GSS panel was 73 percent white, 14 percent African-American, and 13 percent belonged to other racial categories.

Results like this suggest a few conclusions. First, a variety of political and social views, not limited to those involving gender, can serve as symbolic masculinities, allowing men to bolster their gender identities by adopting certain attitudes. They may become less supportive of abortion rights, or parental leave laws, or less likely to support a woman candidate for high office.

Second, instead of uniformly making men more conservative, gender role threat seems to lead to attitude polarization, with men who start off with more liberal views becoming more liberal, and those who start off holding more conservative views becoming more conservative. Men who have a more generally liberal worldview seem to react to threats to traditional masculine identity by further rejecting traditional masculinity, while conservative men react by becoming embracing it more.

Third, this sort of compensating mechanism doesn’t work equally well for all men. Men without strong political views to start with (political independents in the results described above) don’t seem to change their political attitudes very much in the face of economic gender role threat. It seems that if politics isn’t very important to you, you can’t compensate for a loss of relative income by embracing one set of political views or another. This isn’t to say that these men aren’t compensating in some way – but they may be doing it in some fascinating new way that we just haven’t noticed or yet recognized as compensatory behavior.

Dan Cassino is Associate Professor of Political Science in the Department of Social Sciences and History at Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Look on Pinterest, on the front page of the newspaper, and even in our own hands as we scroll through social media feeds on our smartphones: the importance of our home objects is everywhere. I see bestselling books about how to make getting rid of our things (category by category, that is – preferably starting with those seven extra crates of shoes) joyful. I notice how there is a whole host of professions, self-help manuals, and even TV shows dedicated to dealing with the hoarding of home stuff. I see tragic reports of lead-poisoned water coming out of kitchen sinks and into cups that children drink from. I see commentary on how Millennials and Gen Xers don’t want their parents’ heirloom furniture (unless it is midcentury modern, that is). And I come across countless articles and concomitant comments articulating competing sides of the “should our kids have smartphones” debate.

Look on Pinterest, on the front page of the newspaper, and even in our own hands as we scroll through social media feeds on our smartphones: the importance of our home objects is everywhere. I see bestselling books about how to make getting rid of our things (category by category, that is – preferably starting with those seven extra crates of shoes) joyful. I notice how there is a whole host of professions, self-help manuals, and even TV shows dedicated to dealing with the hoarding of home stuff. I see tragic reports of lead-poisoned water coming out of kitchen sinks and into cups that children drink from. I see commentary on how Millennials and Gen Xers don’t want their parents’ heirloom furniture (unless it is midcentury modern, that is). And I come across countless articles and concomitant comments articulating competing sides of the “should our kids have smartphones” debate.