Educational systems and school experiences were fraught with challenges during and following the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Without attending school, students across the country faced a unique form of isolation and lack of connectedness.

Given differential access to educational and social resources and technology amongst the families and communities of these students, we expect that challenges associated with the pandemic disproportionately impacted youth of color. To this end, we investigated whether youth of color differed from their white peers in their sense of belonging.

We defined a sense of belonging as feeling included, respected, and supported, rather than feeling isolated or excluded. Past research explains that sense of belonging matters for students’ well-being and academic success. This research has largely examined school belonging. We expanded past research by also examining social belonging—relationships that are trusting and supportive for youth to feel connected to school and social groups—and community belonging, or how youth felt a sense of connectedness and safety out of school. If minoritized youth report lower senses of belonging, that lack of belonging informs understanding of the compounded disadvantages these youth experience and underscores the need for educational policy and community initiatives to prioritize support for vulnerable youth.

Most survey research on belonging focuses on belonging within the school setting, but we conceptualize belonging as extending beyond the educational context. We emphasize that belonging can be shaped by perceptions of support from the broader surrounding community, and further, that belonging and the contextual factors that shape it may differ critically by demographic group: race, ethnicity, and gender.

Thus, we move beyond a focus on just school belonging to include three other types of social belonging: community belonging (referring to feeling discriminated against or unsafe in the community), out-of-school belonging (referring to experiences with extracurricular/after-school activities), and identity (whether students’ racial/ethnic identities are affirmed or rejected by those around them). We join with other scholars to assert that these measures of social belonging matter for students’ well-being and educational trajectories. In our study published in Educational Researcher, we investigated whether school belonging and social belonging varied by race, ethnicity, and gender for high school and middle school youth in a public school district. Our sample included 1233 youth from fifth to twelfth grade and 40 items about categories of belonging as well as an open ended response question where youth could add additional experiences they have had.

First, we focus on key findings regarding the high school youth in our sample. Using survey data in a midsize district in the Mid-Atlantic, we found that Black and multiracial high school students were less likely than others to feel a strong sense of belonging in their schools. Black high school students also were more likely than other students to feel discriminated against or unsafe in their communities. Hispanic and multiracial high school students reported lower out-of-school belonging, or a lack of connection to social activities and relationships outside of school. We also found that high school students who spoke English as a second language struggled to belong in the after-school setting.

The middle schoolers in our sample were similar, but with some differences. Black middle schoolers reported both struggles to belong within the school setting and in the out-of-school setting; further, Black, Hispanic, and Asian middle schoolers were less likely than other students to feel a lack of belonging in their communities. Middle school students who spoke English as a second language were also less likely than other students to report a lack of belonging in both the community and out-of-school contexts.

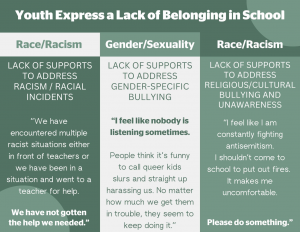

Indeed, minoritized students in our sample reported weaker senses of belonging, both in-school and out-of-school, compared to their white peers. Through analysis of over 600 open-ended response items in the survey, we found that youths’ lack of belonging often stemmed from negative experiences at school, few trusting relationships with adults, and little affirmation from adults in school of students’ identities (e.g., racial/ethnic and language backgrounds). Youth reported various forms of bullying in relation to race, gender identity and religious preferences as well:

Figure A: Youth perspectives on factors that inhibit belonging in schools

Our findings have implications for educational policies. If Black and Latino students, students of immigrant backgrounds, and nonnative English speakers report a lower sense of belonging than their White peers, schools should be intentional in seeking to understand and affirm students’ needs and racial/ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. As many school districts face challenges related to racial inequity, anti-immigrant rhetoric and policy, and anti-Black racism, systems and structures must transform to support marginalized youth. In fact, in the open-ended responses youth reported their desires for change, which included:

“We need to learn about black culture, and other cultures and races and identities generally. It would help to have a more welcoming school envirnment.”

These results underscore the importance of centering youth voices and experiences in efforts for improvement of racial inequity and reducing negative experiences of belonging. Going forward, we hope research further investigates specific reasons for lower belonging amongst racially/ethnically minoritized youth. Additionally, research should aim to identify how school districts can best address race-specific bullying and in the case of this district and districts alike gender, religious and culturally-specific bullying and lack of supportive relationships and affirmation of identities both within-school and in afterschool programs.

Belonging is critical for youths’ well-being and their educational and social trajectories—schools and communities must strive towards fostering belonging for marginalized youth who face compounding social inequities and need to feel safe and connected.

Sophia Rodriguez PhD (@SoRoPhD), is an associate professor of urban education at the University of Maryland, College Park. She is incoming (Fall 2024) associate professor of educational policy studies at New York University. With generous funding from the William T. Grant and Spencer Foundations, her research investigates how community-school partnerships and educators promote equity for immigrant youth; her research appears in AERA Open, Sociology of Race & Ethnicity, Teachers College Record, Urban Education, and the Washington Post.

Gabrielle Cabrera Wy, MA (@GabiCWy), is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her research interests focus on immigrant generational disparities in key life outcomes.

Comments