What do Papua New Guinea, Suriname, and the United States have in common? None of them have a federal paid parental leave policy. The US is clearly out of step with the rest of the world when it comes to this issue. In Fixing Parental Leave: The Six Month Solution (2020, NYU Press), I look to the UK and Sweden for lessons about what might work and what might not work in the US.

What do Papua New Guinea, Suriname, and the United States have in common? None of them have a federal paid parental leave policy. The US is clearly out of step with the rest of the world when it comes to this issue. In Fixing Parental Leave: The Six Month Solution (2020, NYU Press), I look to the UK and Sweden for lessons about what might work and what might not work in the US.

I started with Sweden because that seemed like the obvious starting place. Sweden was the first country to introduce parental leave back in 1974. And gender equality, or jämställdhet, is a huge part of the cultural fabric in Sweden. But I was also worried that the US wouldn’t go from 0 to 480 days of paid parental leave. So I turned to the UK, our closest ally and fellow liberal market economy. I was also hopeful that the UK could offer some ideas after introducing shared parental leave in 2015. Unfortunately, their policy hasn’t panned out, with very low rates of take-up among British fathers. All the same, I learned a lot from closely examining the policies in Sweden and the UK, and I think these lessons pointed me toward the six month solution.

My book discusses 6 main points:

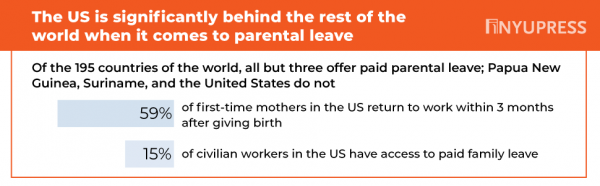

- The US is way behind the rest of the world

The US is the only industrialized country with no paid parental leave at the national level. We are literally in a category by ourselves. There are a handful of states that offer paid family leave, and these may offer insights into how to pay for a federal policy. There are also an increasing number of (mainly large) companies that offer parental leave, but many of these policies are gendered; I created a classification of policies – gender equal, gender modified, gender unequal, gender neutral gendering.

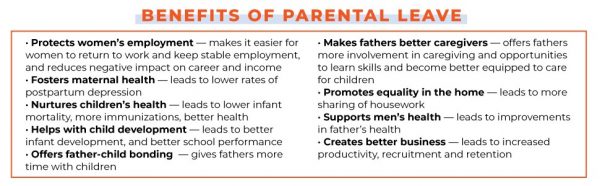

2. Parental leave is good

There are so many benefits of parental leave for mothers, fathers, children, and business. And it has the potential to promote gender equality in the home and workplace, if shared more equally.

3. Too much parental leave is not good

There is a catch. When leave is too long or taken mainly by mothers, it may actually discourage gender equality. It gets more difficult to return to work and mothers often face wage and career penalties. Another downside of too much leave is postpartum depression. Based on a number of studies, it looks like 6 months of leave is the “sweet spot.”

4. Fathers as partners, not helpers

It’s imperative that fathers are equal partners and not simply helpers. When fathers are given very short leave, they often use their limited time at home to support their partner who, by default, become the primary caregiver.

5. The UK is not a good model

When I first went to the UK, I thought surely any policy is better than no policy. Yet, the UK has a track record of a highly gendered model of parental leave with 52 weeks of maternity leave (39 weeks paid) and 2 weeks of paternity leave. Under this system, mothers are assumed to, and generally do, take at least nine months of leave, often returning to work part-time. It’s not surprising then that men don’t do much at home and women struggle to advance in the workplace. Shared Parental Leave, introduced in 2015, hasn’t been effective, mainly because it’s still attached to maternity leave (mothers have to give it up for fathers to take it) and is low paid.

6. The Swedish model is great – but not perfect

Sweden could be the closest to perfect (though Finland’s new policy is dreamy). With 240 days of leave for each parent, it’s clearly a generous policy. In an effort to get fathers to take more leave, Sweden has what’s known as pappamånader, or “daddy quota” of 90 days, meaning that it can only be used by fathers (though the actual policy uses gender-neutral language to apply to any two parents). It’s not really a question of whether Swedish fathers will take parental leave but how much leave, going so far as to say only “oddballs” don’t take leave. But it’s still not equal.

All this suggests the US needs to get its act in shape.

The good news is that the US has a clean slate (I’m a glass half full kind of person). So when we create a paid parental leave policy – and we should do this sooner rather than later – we can do our best to make sure it not only helps workers balance having a new kid with their job but also promotes gender equality at home and work.

Gayle Kaufman is Nancy and Erwin Maddrey Professor of Sociology and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Davidson College. Find out more at https://gaylekaufman.com/ and follow her on twitter @gakaufman22.

Comments 2

billy — May 7, 2024

Keep up the amazing billy nomates glastonbury work, your blog is a must-read for me.

Jennie Fitz — October 3, 2024

"Fixing Parental Leave: The Six Month Solution" advocates for extending parental leave to six months, emphasizing its benefits for family bonding, health outcomes, and workplace equity. This policy can improve employee satisfaction and retention while supporting child development, creating a more inclusive and nurturing environment for all aarpmembership