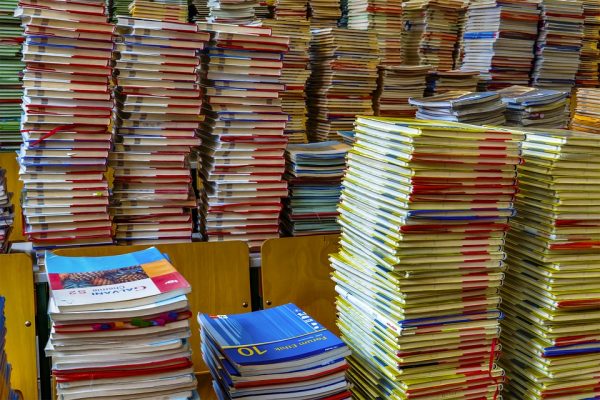

Textbooks are more prevalent in American history courses than in any other subject, and a recent article from The New York Times revealed how geography has influenced what U.S. students learn. Despite having the same publisher, textbooks in California and Texas (the two largest markets for textbooks in the U.S.) vary wildly in educational content. Researchers have also found numerous inconsistencies and inaccuracies in American history textbooks, resulting in the glorification of national figures and spread of national myths.

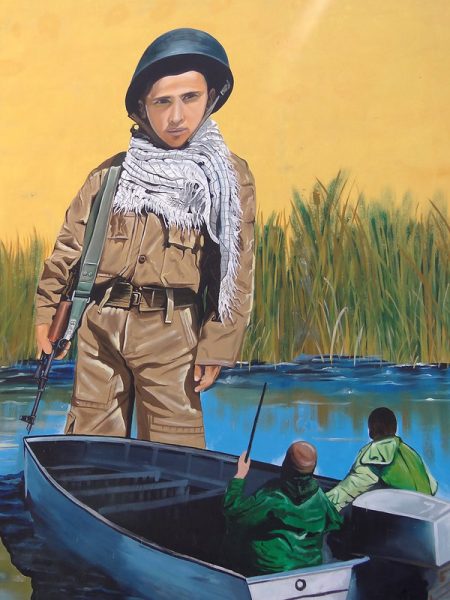

Depictions of violence in textbooks are also highly politicized. Episodes of violence are often muted or emphasized, based on a country’s role in the conflict. For example, conflicts with foreign groups or countries are more likely than internal conflicts to appear in textbooks. Additionally, American textbooks consistently fail to acknowledge non-American casualties in their depictions of war, citing American soldiers as victims, rather than perpetrators of the horrors of war. Depictions of conflicts also vary over time, and as time passes, textbooks move away from nationalistic narratives to focus instead on individualistic narratives.

- Elizabeth Cole, ed. 2007. Teaching the violent past: History education and reconciliation. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Sylvie Guichard. 2013. “The Indian nation and selective amnesia: representing conflicts and violence in Indian history textbooks.” Nations and Nationalism, 19(1), 68-86.

- Lachmann, Richard and Lacy Mitchell. 2014. “The Changing Face of War in Textbooks: Depictions of World War II and Vietnam, 1970-2009.” Sociology of Education 87(3): 188-203.

- Joachim Savelsberg and Ryan D. King. 2011. American Memories: Atrocities and the Law. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Public figures, like Hellen Keller and Abraham Lincoln, tend to be “heroified” in American textbooks. Rather than treating these public figures as flawed individuals who have accomplished great things, American textbooks whitewash their personal histories. For example, textbooks overlook Keller’s fight for socialism and support of the USSR and Lincoln’s racist beliefs. The heroification of these figures is meant to inspire the myth of the American Dream — that if you work hard, you can achieve anything, despite humble beginnings.

- Barry Schwartz and Howard Schuman. 2005. “History, Commemoration, and Belief: Abraham Lincoln in American Memory, 1945-2001.” American Sociological Review 70(2): 183-203.

- James W. Loewen. 1995 [2007]. Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. New York: Touchstone.

Symbolic representation of the past is important in stratified societies because it affects how individuals think about their society. Emphasizing the achievements of individuals with humble beginnings promotes the belief among American students that if they work hard they can achieve their goals, despite overwhelming structural inequalities. Furthermore, as historical knowledge is passed down from one generation to the next, this knowledge becomes institutionalized and reified–making it more difficult to challenge or question.

- Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Anchor Books.

- Karl Mannheim. 1936. Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge. San Diego: Harcourt.

- William L Griffen and John Marciano. 1979. Teaching the Vietnam War. Montclair, NJ: Allanheld.