My sister-in-law Charlotte was recently loudly admonished by a flight attendant on an international flight for allowing her “breast to fall out” after she fell asleep while nursing her baby. A strong advocate for breastfeeding, Charlotte has shared with me her own discomfort with public breastfeeding because it is considered gross, matronly, and “unsexy.”

I heard this over and over again from women I have interviewed for my research: Women who breastfed often feel they have to cover and hide while breastfeeding at family functions. As one mom noted, “Family members might be uncomfortable so I leave room to nurse—but miss out on socializing.” This brings on feelings of isolation and alienation. Because of the “dirty looks” and clear discomfort by others, women reported not wanting to breastfeed in any situation that could be considered “public.”

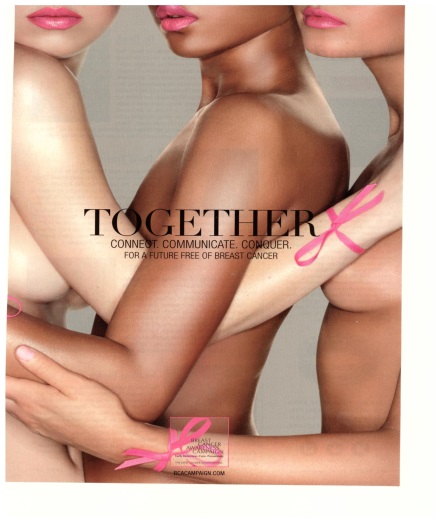

Meanwhile, I flip through the June 2012 issue of Vanity Fair and see this ad:

We capitalize on the sexualization of the breast to raise awareness about breast cancer. Yet, we cringe at the idea of a woman nursing her child on an overnight flight.

What’s happening here? These campaigns send contradictory messages to women about their breasts and the way women should use them, but they have something in common as well: both breastfeeding advocacy and breast cancer awareness-raising campaigns tend to reduce women to body parts that reflect the social construction of gender and sexuality.

Breast cancer awareness campaigns explicitly adopt a sexual stance, focusing on men’s desire for breasts and women’s desire to have breasts to make them attractive to men. Breast milk advocates focus on the breast as essential for good motherhood. Breastfeeding mothers sit at the crossroads: Their breasts are both sexualized and essential for their babies, so they can either breastfeed and invoke disgust, or feed their child formula and attract the stigma of being a bad mother.

Both breastfeeding advocacy programs and breast cancer awareness-raising campaigns demonstrate how socially constructed notions of ownership and power converge with the sexualization and objectification of women’s breasts. And, indeed, whether breast feeding or suffering breast cancer, women report feeling helpless and not in control of their bodies. As Jazmine Walker has written, efforts to “help” women actually “[pit] women against their own bodies.”

Instead, we need to shift away from a breast-centered approach to a women-centered approach for both types of campaigns. We need to, as Jazmine Walker advocates, “teach women and girls how to navigate and control their experiences with health care professionals,” instead of pushing pink garb and products and sexualizing attempts to raise awareness like “save the ta-tas.” Likewise, we need to support women’s efforts to breastfeed, if they choose to, instead of labeling “bad moms” if they do not or cannot. Equipped with information and bolstered by real sources of support, women will be best able to empower themselves.

Jennifer Rothchild, PhD is in the sociology and gender, women, & sexuality studies departments at the University of Minnesota, Morris. She is the author of Gender Trouble Makers: Education and Empowerment in Nepal and is currently doing research on the politics of breastfeeding.

Comments 24

Bill R — December 16, 2014

I am with you 100% and I would take it even further.

Forget about limiting this to the breast cancer and breast feeding "campaigns" and let's put an end to the entire dress-to-be-sexy "campaign". Lifting, separating, cleavage, for chrissake already, haven't we had enough? Can't women simply dressed nicely, to be comfortable?

Let's stop dressing to emphasize sexuality. If we do we will not have breast-feeding in public problems…

Elias — December 16, 2014

Nice article, I only wish you'd avoid language like "social construction of gender and sexuality", "socially constructed notions of ownership and power".

I live for the day when sociologists will perceive their duty to be towards common people, not fellow sociologists

Esme — December 16, 2014

This image also demonstrates another awful thing in breast cancer cause related marketing: decapitation. These ads frequently shoot from the neck down, dehumanizing the subjects and further reducing them to walking pairs of breasts.

LauraTee — December 16, 2014

Anyone who thinks that fighting breast cancer is about saving breasts (as in the ridiculous "Save the Tatas") hasn't had a loved one die a horrible death from the disease. It's come to a point that I'm just instantly livid when I see another one of those inane Facebook posts (from people who I'm sure are well-meaning).

Because you know what breast cancer looks like for me? It looks like my aunt, the kindest, most generous person I've ever known, learning three days before her 60th birthday that her entire spine and skull had been completely replaced by cancer. She suffered in agony for months, out of her mind due to either pain or morphine 24/7. She was terrified to die and clung to the impossible hope of recovery. And in the midst of the horror of witnessing her big sister die in this tortuous way, my mom was diagnosed with breast cancer too. She went through her treatments while watching the inevitable outcome of what would happen if they didn't work.

None of it had anything to do with cutesy "campaigns" or pink merchandise. It had barely anything to do with breasts at all. Breast cancer isn't about that. Breast cancer is about pain, suffering, and death. It is about a horrific disease, and there is something so disgusting about trying to make that somehow upbeat or cute or positive.

Sofia — December 16, 2014

This reminds me of the Terror Management Theory (http://www.tmt.missouri.edu). According to this theory, human beings are faced with an existential paradox as they strive for survival; but, unlike other living beings, are aware of their own mortality. The theory goes on to propose a dual defensive system against the terror that the thought of death could arise on us. Then, some of the research, propose that the clearest confrontation with this existential paradox is our own body: we need our body to live, but it is the part of ourselves that we can't deny that it will die. Then it says that the female body might arise more concerns about death than the male body because "its closer to nature" (?!) and its body fluids (such as menstrual blood and breast milk) remind us of its mortality. Then it says that the objectification of the female body "serves the function" (?!) of transforming it into a symbolic object of beauty and value, and this way try to escape the existential anxiety.

I don't agree with this theory, and specially with its idea of the body, but some cultural references to the body keeps reminding me of the TMT.

Guest — December 17, 2014

Breastfeeding women continue to face social stigmas and institutional barriers as well as pressure corporate marketing strategies to use formula. In the past, these campaigns have played on race and class stereotypes to convince mothers that breastfeeding was unsanitary, uncivilized and "gross," which breastfeeding advocates have tried to counter by supporting breastfeeding mothers, emphasizing the advantages breastmilk and trying to ban infant formula marketing campaigns from maternity wards.

It is possible women who can't or choose not to breastfeed feel stigmatized by efforts to highlight its value. At the same time, those efforts have led to laws being passed to make it easier for women to choose that option. For example, ObamaCare amended the Fair Labor Standards Act to give nursing mothers the right to breaks and private rooms so they can pump during the workday. This is great for nursing mothers, and a historic advance for the feminist project of workplace equality.

Andrew — December 17, 2014

Exposed breasts, be they in Vanity Fair ads or in public places, are perfectly normal in the US (which I assume to be the cultural reference point here). It's exposed nipples that people seem to be freaking out about. Even when we're sexualizing breasts as in the homoerotic ad above, nipples have to be airbrushed out - otherwise it's deemed to be pornography. Similarly, a ludicrous distinction is drawn between a breastfeeding mom whose nipple has "slipped" out and the exact same woman wearing a low-cut blouse revealing lots of cleavage.

We expect female celebrities to present their breasts on sparkly silver platters every time they get dressed up for the cameras, but if their nipples become visible it's deemed a "wardrobe malfunction" and it makes the news - with the offending body part dutifully pixellated out.

This is extremely silly and juvenile. But when female nipples are routinely censored out of ordinary content, it's understandable that people's reflexive reaction to the sight of one is going to be shock. Like, "oh no, the airplane has suddenly become R-rated!" I'd suggest that the same standards be applied to nipples of all genders, and we'll see what that does for breastfeeding.

The Paradox of Women’s Sexuality in Breast Feeding Advocacy and Breast Cancer Campaigns - Treat Them Better — December 17, 2014

[…] (View original at http://thesocietypages.org/socimages) […]

Rebecca — December 18, 2014

I do get tired of scholars and journalists telling the world everything that is wrong with breastfeeding advocacy, without ever speaking with an actual breastfeeding advocate or looking at what breastfeeding advocacy is actually saying nowadays. It's almost de rigeur for many feminist scholars to prove their feminist cred by casting all efforts to promote and support breastfeeding as moralistic, judgmental, classist, etc.

Of course, there's a history to this troubled relationship between breastfeeding and feminism, but there is actually a LOT of fabulously feminist breastfeeding advocacy and scholarship out there now. It would be nice if this essay had linked to some actual breastfeeding advocacy sites rather than assuming that all of us are just doing the same thing LLL was doing back in the 1970s and 80s (when, yes, it was largely about calling breastfeeding "good mothering" and telling women to stay at home with their children.)

Today's breastfeeding advocacy includes a great deal of the woman-centered messaging and support that this piece calls for. See Best for Babes, Breastfeeding USA, KellyMom, the United States Breastfeeding Committee, the Breastfeeding and Feminism International Conference, the work of scholars like anthropologist Penny van Esterik, critical theorist Bernice Hausman, historian Jacqueline Wolf, blogs like PhD in Parenting, Evolutionary Parenting, and the Feminist Breeder ... just to list a smattering of available sites and resources.

Breast are Beautiful Except When Feeding Babies | bestieswithablog — December 18, 2014

[…] Being interested in sociology, I am naturally intrigued by why our society so readily accepts women baring all on the beaches at spring break but as soon as a baby is brought into the picture and boobs are used they were intended to be it is all of a sudden revolting. I ran across this gem and thought I need to share: The Paradox of Women’s Sexuality In Breastfeeding Advocacy and Breast Cancer Campaignes […]

Sexy Cancer, Obscene Eating, and the Social Breast | human with uterus — December 18, 2014

[…] Sociological Images addressed two issues that have been pet peeves of mine for a long time, namely the sexualization of breast cancer and the sexualizing of breastfeeding. The piece compares the admonishment of the author’s sister-in-law for allowing her “breast to fall out” when she fell asleep nursing on a plane and this 2012 ad for breast cancer awareness: […]

The Woman in Shorties – Bridget Magnus and the World as Seen from 4'11" — December 19, 2014

[…] Finally: Boobs and Man […]

Sexualization of Breasts in Breast Cancer Ad Campaigns and Breastfeeding Advocacy | floweren — December 19, 2014

[…] a look at this article from Sociological Image about the sexualization and body fragmentation of women’s breasts […]

Daily Feminist Cheat Sheet — December 24, 2014

[…] is public breast-feeding considered unsexy and inappropriate, but we normalize breasts as sexy when it comes to campaigns to fight breast […]

thebreastfeedinglady305 — December 26, 2014

How bout uniting thr two? Maybe there should be an add saying..." Breastfeed! It reduces the risk of breast cancer by 35℅." Or " The longer you breastfeed the more percentage rate you have to save your breast from ever developing breast cancer." Or " Love the women in your life, encourage her to breastfeed to help protect herself from breast cancer."

The Paradox of Women’s Sexuality in Breast Feeding Advocacy and Breast Cancer Campaigns - Breast Cancer Consortium — May 9, 2016

[…] is currently doing research on the politics of breastfeeding. Her essay was originally published on Sociological Images at The Society Pages on Dec. 16, 2014, with a Creative Commons […]