For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2012.

Today, most people in the U.S. see childhood as a stage distinct from adulthood, and even from adolescence. We think children are more vulnerable and innocent than adults and should be protected from many of the burdens and responsibilities that adult life requires. But as Sidney Mintz explains in Huck’s Raft: A History of American Childhood, “…childhood is not an unchanging biological stage of life but is, rather, a social and cultural construct…Nor is childhood an uncontested concept” (p. viii). Indeed,

We cling to a fantasy that once upon a time childhood and youth were years of carefree adventure…The notion of a long childhood, devoted to education and free from adult responsibilities, is a very recent invention, and one that became a reality for a majority of children only after World War II. (p. 2)

Our ideas about what is appropriate for children to do has changed radically over time, often as a result of political and cultural battles between groups with different ideas about the best way to treat children. Most of us would be shocked by the level of adult responsibilities children were routinely expected to shoulder a century ago.

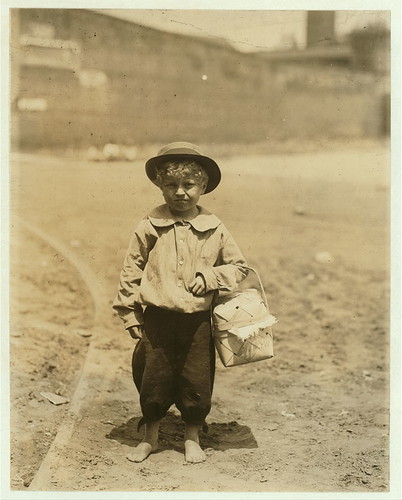

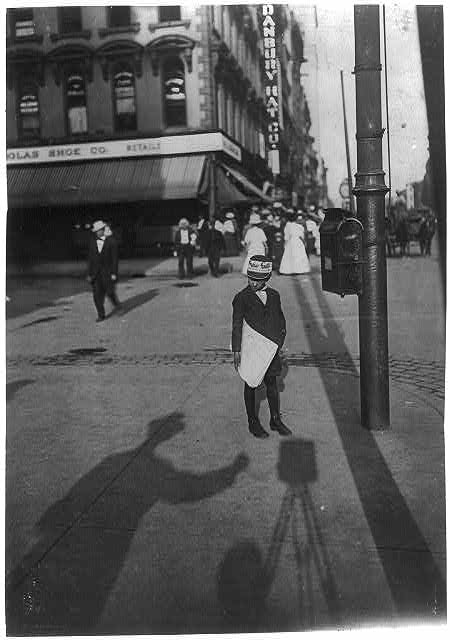

Reader RunTraveler let us know that the Library of Congress has posted a collection of photos by Lewis Hine, all depicting child labor in the early 1900s in the U.S. The photos are a great illustration of our changing ideas about childhood, showing the range of jobs, many requiring very long hours in often dangerous or extremely unpleasant conditions, that children did. I picked out a few (with some of Hine’s comments on each one below each photo), but I suggest looking through the full Flikr set or the full collection of over 5,000 photos of child laborers from the National Child Labor Committee:

“John Howell, an Indianapolis newsboy, makes $.75 some days. Begins at 6 a.m., Sundays.” 1908. Source.

“Interior of tobacco shed, Hawthorn Farm. Girls in foreground are 8, 9, and 10 years old. The 10 yr. old makes 50 cents a day.” 1917. Source.

“Interior of tobacco shed, Hawthorn Farm. Girls in foreground are 8, 9, and 10 years old. The 10 yr. old makes 50 cents a day.” 1917. Source.

“Eagle and Phoenix Mill. ‘Dinner-toters’ waiting for the gate to open.” 1913. Source.

“Eagle and Phoenix Mill. ‘Dinner-toters’ waiting for the gate to open.” 1913. Source.

“Vance, a Trapper Boy, 15 years old. Has trapped for several years in a West Va. Coal mine. $.75 a day for 10 hours work. All he does is to open and shut this door: most of the time he sits here idle, waiting for the cars to come. On account of the intense darkness in the mine, the hieroglyphics on the door were not visible until plate was developed.” 1908. Source.

“Vance, a Trapper Boy, 15 years old. Has trapped for several years in a West Va. Coal mine. $.75 a day for 10 hours work. All he does is to open and shut this door: most of the time he sits here idle, waiting for the cars to come. On account of the intense darkness in the mine, the hieroglyphics on the door were not visible until plate was developed.” 1908. Source.

“Rose Biodo…10 years old. Working 3 summers. Minds baby and carries berries, two pecks at a time. Whites Bog, Brown Mills, N.J. This is the fourth week of school and the people here expect to remain two weeks more.” 1910. Source.

“Rose Biodo…10 years old. Working 3 summers. Minds baby and carries berries, two pecks at a time. Whites Bog, Brown Mills, N.J. This is the fourth week of school and the people here expect to remain two weeks more.” 1910. Source.

Hine’s photos make it clear how common child labor was, but their very existence also documents the cultural battle over the meaning of childhood taking place in the 1900s. Hine worked for the National Child Labor Committee, and his photos and especially his accompanying commentary express concern that children were doing work that was dangerous, difficult, poorly-paid, and that interfered with their school attendance.

In fact, the NCLC’s efforts contributed to the passage of the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act in 1916, the first law to regulate the use of child workers (limiting hours and forbidding interstate commerce in items produced by children under various ages, depending on the product). The law was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1918. This resulted in an extended battle between supporters and opponents of child labor laws, as another law was passed and then struck down by the courts, followed by successful efforts to stall any more legislation in the 1920s based on states-rights and anti-Communist arguments. Only in 1938, with the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act as part of the New Deal, did child workers receive specific protections.

Even then, we had loopholes. While children working in factories or mines was redefined as inappropriate and even exploitative and cruel, a child babysitting or delivering newspapers for money was often interpreted as character-building. Today, the cultural battle over the use of children as workers continues. This year, the Labor Department retracted suggested changes that would restrict the type of farmwork children could be hired to do after it received significant push-back from farmers and legislators afraid it would apply to kids working on their own family’s farms.

As Mintz said, childhood is a contested concept, and the struggle to decide what kind of work, if any, is appropriate for any child to do continues.

For more examples, see Lisa’s 2009 post about child labor.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

Comments 43

Tyler Bickford — September 4, 2012

It's Steven, not Sidney, Mintz

glaborous_immolate — September 4, 2012

So if i think its not appropriate for a kid to work in a factory, i'm not more humane and moral and ethical and caring? And if kids stop working in factories it isn't progress towards justice?

I'm just contending for my preference, like telling people chocolate is really tasty?

Vadim McNab — September 4, 2012

This sentence is a social construct.

Guest — September 4, 2012

I live in a city where companies employ sign holders. People are paid to stand on busy streets holding signs for the thrift store, etc. Yesterday I saw a boy of about 9 holding a sign for a pizza place. I was surprised and figured he must be related to the business owner, because otherwise it would not be allowed. He was standing directly in front of the business, but I saw no adult on the street with him. It made me uncomfortable.

Tusconian — September 4, 2012

"While children working in factories or mines was redefined as

inappropriate and even exploitative and cruel, a child babysitting or

delivering newspapers for money was often interpreted as

character-building."

There are fundamental differences between a 7 year old working in a 1900s era factory and a 12 year old minding a couple of toddlers or flinging newspapers, though. Sure, there are risks to all of these things (a young babysitter may be more likely to accidentally hurt a child, a kid on a paper route may be at risk of abduction or falling off a bike and not being missed for hours), but there's the difference between "actively dangerous" and "a bit risky." Also, those things don't inherently interfere were schooling. Paper routes tended to be early in the morning, before school, and babysitting in the evenings or on weekends. Yes, some things are socially constructed, but most social constructs are based on real things. Children AREN'T just tiny adults. Biologically, emotionally, physically, or mentally.

decius — September 4, 2012

I think the shift away from child labor is mostly due to the decrease in labor requirements overall; what was the unemployment rate in areas where children were being used for agriculture or factory work?

robyn krafterson — September 5, 2012

Last year I went through a phase of eating up Horatio Alger books

written for adolescent boys featuring child laborers

(http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/168). Some of the series are

about orphans working on the street as newsies, bootblacks, luggage

smashers, etc. -- eg: The Ragged Dick Series, and The Tattered Tom Series. In The Brave and Bold Series,

boys young as 10-12 yrs farming in lieu of a dead parent to save their

home from foreclosure, or set off cross-country to NYC in search of

fortune to support a farm family.

Neverminding the "be

industrious to pull yourself up by your bootstraps" narrative, the

stories in the series helped shed light on the poor living conditions

and general hard times of the child orphans left to fend for themselves

on the streets or working to save their families. They're quick fluffy

reads, and I highly reccomend them (I read most of them even though the

plot is basically the same in each book).

In the beginning of

several of the books, there was a note from Alger explaining that the

characters were based on boys he met on the street. Before they were

published as books many were released as serials in the papers. Alger

wanted the books/stories to raise awareness of the boys' plight, and he

intended for them to be published and left in the lodging-houses to help

and encourage the boys to learn to read.

So for anyone

interested in some context for child labor, or especially the freedoms

that kids had that differ so much from today, read up public domain

books written for children or adolescents. They obviously won't tell the

whole story, and the meme of the times was to write books of glowingly

virtuous children being and doing good, but they paint a cultural

picture. A lot of it makes for a quick easy read.

Here's a link to children's fiction: http://www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Children%27s_Book_Series_%28Bookshelf%29

(I happened to enjoy The Automobile Girls series myself.)

CHILD LABOR AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF CHILDHOOD #GreatRead « Welcome to the Doctor's Office — September 5, 2012

[...] from SocImages [...]

famousblueraincoat — September 5, 2012

it is quite possible that the clothes I am wearing were made by a child working in a factory. I am sure there are many photos from 2012 that show children working in factories. Should this be seen as part of a developing countries evolution as the case of America in 1900 or just the global west willing to exploit workers so they can sell me cheap clothes. I wish I could take the moral highground here but I am not sure if I would be willing to pay more for my clothes. This in itself is quite depressing.

4. Socialization & the Construction of Reality: Inventing Childhood | Angel Huipio — September 6, 2012

[...] Sharp, G. (2012, September 4). Child labor and the social construction of childhood. Sociological Images. Retrieved from http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2012/09/04/child-labor-and-the-social-construction-of-childhood... [...]

Photos of the Day: CHILD LABOR « lara harlow-hentz — September 17, 2012

[...] Child Labor and the Social Construction of Childhood by Gwen Sharp, http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2012/09/04/child-labor-and-the-social-construction-of-childhood... [...]

Donnette Lee — September 21, 2012

The concept of Childhood is interesting, because of its evolution. However, the reality of the 1900s has not disappeared, where children still have to work to provide for their family. The forgotten Children of Zimbabwe is a documentary that was created two years ago that reflects a similar idea of childhood in the 1900s:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDezIzugLXU . I still never really considered how ambiguous the concept of childhood could be.

Dječji rad i društvena konstrukcija djetinjstva » Centar za društveno-humanistička istraživanja — October 15, 2012

[...] Sharp, autorica na thesocietypages.org, osvrće se na promjene tijekom prošlog stoljeća koje se odnose na prikladnost korištenja djece [...]

Through the Eyes of a Working Child | Children, Youth and Society — March 10, 2014

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2012/12/28/child-labor-and-the-social-construction-of-childhood… […]

vintage florals, spiderwebs, & watermelon | My Kingdom for a Hat — March 12, 2015

[…] I think the blurring of age distinctions is great. Age categories are fluid and socially constructed, not immutable. I’ve never been a fan of segregating media by age, anyway. Art is art. Why […]

POW! Right in the childhood! | steveboutilier — June 13, 2016

[…] media represents a huge threat to childhood. While there is no doubt that childhood is a fairly modern social construct, I still believe that it should be protected vigorously. I often tell my students to treasure this […]