This year’s top ten sexual stories: an incomplete list from our subjective, North American perspective, containing a mixture of disturbing, entertaining, and hopeful developments.

10. Katie Perry got kicked off Sesame Street

“Thursday morning, the PBS children’s show announced that a scheduled appearance by Perry, queen of the most inappropriate whipped-cream bra ever, had been canceled. On Monday, a clip of Perrywearing a sweetheart-cut dress, singing a G-rated version of her hit “Hot N Cold” and begging to “play” with Elmo, was leaked on the Web. Parents, outraged by Perry’s C-cup-accentuating dress,immediately protested. “You’re going to have to rename [Sesame Street] Cleavage Avenue,” wrote one commenter, while another simply joked, “My kid wants milk now.” (LA Times, Sept. 23, 2010).

9. George Rekers got caught with “rent boy”

“Reached by New Times before a trip to Bermuda, Rekers said he learned Lucien was a prostitute only midway through their vacation. “I had surgery,” Rekers said, “and I can’t lift luggage. That’s why I hired him.” (Medical problems didn’t stop him from pushing the tottering baggage cart through MIA.)” (Bullock, P. and Thorp, B., Miami New Times, May 6, 2010).

8. Constance McMillen barred from her prom, becomes a Glamour Magazine “Women of the Year“

“Constance McMillen has been named one of Glamour Magazine’s ‘Women of the Year’ for 2010. We came to know Constance through her personal ordeal with Itawamba Agricultural High School in Fulton, Mississippi. The school board rejected her request to bring her girlfriend to the prom as her date, and even further, didn’t allow Constance to wear a tuxedo as she had planned.” (Sledjeski, J. GLAAD, Nov. 5, 2010).

7. This one is a tie between: a) Republicans got caught at W. Hollywood Strip Club

“The “family values” Republican National Committee spent almost $2,000 last month at an erotic, bondage-themed West Hollywood club, where nearly naked women – and men – simulate sex in nets hung from above.” (Bazinet, K, and Saltonstall, D. Daily News, March 29, 2010).

and b) Strippers protest Ohio church

“For the past four years, Pastor Dunfee and some of his New Beginnings church members have picketed and protested the strip club in their local community; they’ve even videotaped visitors to the club and posted the videos online in an attempt to hold them accountable for their actions. Pastor Dunfee said the regular protests were to avoid “sharing territory with the devil.”

Irritated by the protests, employees of the club have decided to protest the church—they arrived early in the morning Monday wearing swimwear and toting barbeques, picnic food, sunscreen, and lawn chairs, along with signs reading Matthew 7:15: Beware of false prophets who come to you in sheep’s clothing and Revelation 22:11: He that is unjust, let him be unjust still. ” (Aug.16, 2010; ChurchLeaders.com).

6. European Court of Human Rights Rejects Irish Ban on Abortion

“In December, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Ireland’s constitutional ban on abortion violates the rights of pregnant women to receive proper medical care in life-threatening cases. Each year, more than 6,000 women travel abroad from Ireland to obtain abortion services, often at costs of over $1,500 per trip. In a statement on the ruling, the Irish Family Planning Association—the IWHC partner that helped bring about this decision—said the court sent “a very strong message that the State can no longer ignore the imperative to legislate for abortion.” (Top Ten Wins, International Women’s Health Coalition, December 23, 2010).

5. Millions searched for their G-spot

“Asking if the “G-spot” exists can be a bit like asking if God (the other G-spot) exists: It depends on who you ask. And in both cases, science is (thus far) ill equipped to adequately measure either G-spot. ”

(Lerum, K. Sexuality & Society, Jan 6, 2010).

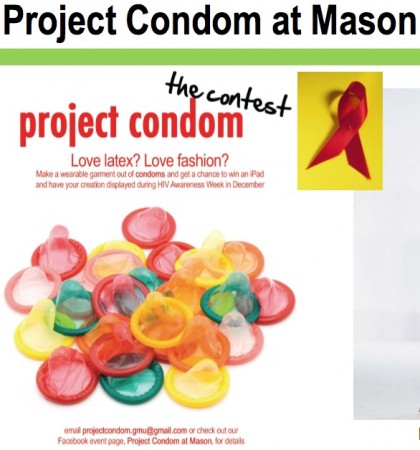

4. The Pope OKs condoms in some circumstances

“In a break with his traditional teaching, Pope Benedict XVI has said the use of condoms is acceptable “in certain cases”, in an extended interview to be published this week.”

“After holding firm during his papacy to the Vatican’s blanket ban on the use of contraceptives, Benedict’s surprise comments will shock conservatives in the Catholic church while finding favour with senior Vatican figures who are pushing for a new line on the issue as HIV ravages Africa.” (Kington, T., and Quinn, B. Guardian UK, Nov. 21, 2010).

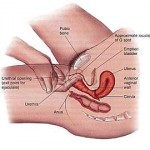

3. Microbicide Research offers hope for HIV prevention

“More than 20 years ago, the International Women’s Health Coalition (IWHC) convened 44 women from 20 countries who conceived of a substance, like contraceptive foam or jelly, which could be inserted vaginally to prevent HIV infection. We named it a “microbicide,” and set out to find scientists and money to develop it. Until recently, progress has been slow, but in July, results from a clinical trial in South Africa found a new gel to be nearly 40 percent effective in protecting women against HIV during intercourse.” (Top Ten Wins, International Women’s Health Coalition, December 23, 2010).

2. Gay Teen Suicide & Bullying as a Social Problem

“The recent rash of high profile suicides by boys who were bullied for gender and sexual non-conformity has created a wake up call for parents and school administrators in the U.S. To create a broader base of support from heterosexual allies, as well as to reach out to GLBT youth themselves, a number of new educational and activist initiatives have emerged. Dan Savage created the “It Gets Better”video project, directed at GLBT youth in despair over hostile treatment and at risk of killing themselves. The Gay and Lesbian Alliance against Defamation (GLAAD) declared Oct. 20, 2010 Spirit Day to call attention to and memorialize the recent suicides. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton even released her own version of an “It Gets Better” video. ” (Lerum, K. Sexuality & Society, Nov. 18 2010).

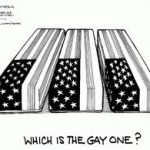

1. The Repeal of “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell”

WASHINGTON — “The military’s longstanding ban on service by gays and lesbians came to a historic and symbolic end on Wednesday, asPresident Obama signed legislation repealing “don’t ask, don’t tell,” the contentious 17-year old Clinton-era law that sought to allow gays to serve under the terms of an uneasy compromise that required them to keep their sexuality a secret.” (New York Times, Dec. 22, 2010).

——————————————————————–

Related Story: Top Ten Sexual Stories of 2009

This NYT piece focused on the number of U.S. high schools who have created dress codes that explicitly classify “unconventional gender expression” as violations warranting disciplinary actions. Hoffman also mentioned some high schools whose dress codes are more accepting of “gender-blurring clothing.” Hoffman’s recent NYT article includes arguments for and against dress codes that allow for a diverse range of gender and sexuality expressions, noting safety as “a critical concern.”

This NYT piece focused on the number of U.S. high schools who have created dress codes that explicitly classify “unconventional gender expression” as violations warranting disciplinary actions. Hoffman also mentioned some high schools whose dress codes are more accepting of “gender-blurring clothing.” Hoffman’s recent NYT article includes arguments for and against dress codes that allow for a diverse range of gender and sexuality expressions, noting safety as “a critical concern.” Morehouse College is a small all-male college in Atlanta Georgia with 2,700 students. It has recently instituted a ban on women’s clothing, high heels, and carrying purses within its student body. Dr. William Bynum, vice president for Student Services reported that “We are talking about five students who are living a gay lifestyle that is leading them to dress a way we do not expect in Morehouse men.” CNN reports that the college has stated that those who are found breaking the policy will not be allowed to go to class unless they change. The school also reports that “chronic dress-code offenders could be suspended from the college.”

Morehouse College is a small all-male college in Atlanta Georgia with 2,700 students. It has recently instituted a ban on women’s clothing, high heels, and carrying purses within its student body. Dr. William Bynum, vice president for Student Services reported that “We are talking about five students who are living a gay lifestyle that is leading them to dress a way we do not expect in Morehouse men.” CNN reports that the college has stated that those who are found breaking the policy will not be allowed to go to class unless they change. The school also reports that “chronic dress-code offenders could be suspended from the college.” Stuart Hall, in his seminal work on social inequality and culture (titled Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices), defines how a sense of “othering” develops among more powerless groups when marked as “different” from (and often inferior to) dominant groups. “Othering” as you can see is a verb and refers to how powerless groups are marked and viewed as different and then frequently treated differentially by dominant groups on the basis of such markings. Marginalized groups, in turn, frequently come to see themselves as “different from” dominant groups and, at times, take on the qualities of dominant groups so as to assure that the possibilities for acceptance and upward mobility are not squelched within “mainstream society.” For African-American men in particular, as a response to having a lack of access to traditional means of masculinity (e.g. the occupational structure and mobility within it), scholars have further suggested that many African-American men adopt a “cool pose” that exaggerates attributes of masculine prowess (physicality and sexuality) to compensate for the lack of empowerment in other areas of their lives (Staples, 2006; Majors & Bilson, 1993; Messner, 1997). This process is said to be due to institutional and personal racism and discrimination which deny many African-American men traditional opportunities for masculine affirmation (e.g., education, employment, etc.). Behaviors to constitute hegemonic masculinity (the most dominant form of masculinity in a given period–often middle class and heterosexual), often include those that conform to gender role expectations that signify masculinity not only in the African-American community but broader society more generally.

Stuart Hall, in his seminal work on social inequality and culture (titled Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices), defines how a sense of “othering” develops among more powerless groups when marked as “different” from (and often inferior to) dominant groups. “Othering” as you can see is a verb and refers to how powerless groups are marked and viewed as different and then frequently treated differentially by dominant groups on the basis of such markings. Marginalized groups, in turn, frequently come to see themselves as “different from” dominant groups and, at times, take on the qualities of dominant groups so as to assure that the possibilities for acceptance and upward mobility are not squelched within “mainstream society.” For African-American men in particular, as a response to having a lack of access to traditional means of masculinity (e.g. the occupational structure and mobility within it), scholars have further suggested that many African-American men adopt a “cool pose” that exaggerates attributes of masculine prowess (physicality and sexuality) to compensate for the lack of empowerment in other areas of their lives (Staples, 2006; Majors & Bilson, 1993; Messner, 1997). This process is said to be due to institutional and personal racism and discrimination which deny many African-American men traditional opportunities for masculine affirmation (e.g., education, employment, etc.). Behaviors to constitute hegemonic masculinity (the most dominant form of masculinity in a given period–often middle class and heterosexual), often include those that conform to gender role expectations that signify masculinity not only in the African-American community but broader society more generally.