Revisit this March 2018 interview with Jessica Fulton to celebrate her new position at the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies as their Economic Policy Director. As their twitter description puts it the Joint Center is currently focused on the future of work and congressional staff diversity. Jessica generously gave her time last spring to Framingham State University students seeking to learn about careers in public policy for Black women.

Last month I got to interview Jessica Fulton via Skype to learn more about her career and her work. She is the External Relations Director at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Equitable Growth is a research and analysis organization that is dedicated to finding ways to promote broad-based economic growth. Before Jessica was at EG, she was the Outreach Director at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute, an organization that focuses on budget issues for the District of Columbia. Jessica is an alum of the University of Chicago, where she received her Bachelor’s degree in Economics, and of DePaul University, where she earned a Masters in Economic Policy Analysis. Our conversation—and the interview below—focused on my desire to get some pointers on how more young women of color can make a difference in social policy.

EO: What are your top pieces of advice to young minority women seeking to work in social policy?

JF: If you’re able, try to get an internship in DC so that you’re able to learn more about how things work here. There are a few organizations and Members of Congress that pay their interns, and that’s obviously ideal, but many don’t. If you’re unable to find a paid internship, and can’t afford to take an unpaid one, consider alternate ways of getting into policy work. I know people who got their start by working in a paid position on a campaign of a candidate they really believed in. Others found entry level assistant positions to get their foot in the door. You can also consider getting an unpaid internship and supplementing it with a part time job, which is what I did.

Also, it’s much easier to get a job in DC if you’re actually in DC. It’s really expensive to live here, but if you can come sleep on a friend’s couch for a bit, you can set up interviews, informational conversations, and networking opportunities that could get you some meaningful connections. You should also try applying for jobs with a local address on your resume if possible.

EO: How do you advise people to zero in on areas of focus?

JF: I think one of the most important things that you can do is to start to get to know people who are working on the topics that excite you most. Ask people you know for introductions to people who might be willing to sit down with you to do informational interviews. If you don’t have connections already, think about your networks. Are there alumni from your university who might be willing to speak with you? Do your professors know people who work in social policy? Talking to those people about what they do and what their days look like can be a great way to figure out what you want to do.

You should also try to sign up for newsletters from the particular policy organizations or Members of Congress that you’re interested in. That way, you can get to know more about the topics different organizations work on and what they actually do. This could be helpful in future interviews, but also may help you to figure out which specific issue areas you have a passion for.

EO: Why are young minority women so important to the work of social policy?

JF: A good number of social policy issues disproportionately affect people of color, yet there are usually very few of us in the room when the problems or the solutions are being discussed. And while things are slowly getting better, often women of color, especially black women, aren’t at the decision making tables even if they are part of a policy organization. I think that’s actually really important. For example, when I walk into a room, I’m bringing my education and work experience, but I’m also bringing my life experience and that of my friends and family members. The other folks in the room have important perspectives as well, but my friends, family members, and even myself, are more likely to have experienced certain obstacles and situations that are more common in minority communities. So when I’m thinking about problems and solutions, I can’t help but to look at it through that lens as well. And I think in the end, when you consider how any kind of problem solving works, the most effective solution is one where you’ve considered a diverse set of perspectives to arrive at your conclusion.

Jessica Fulton is now Economic Policy Director for the Joint Center. You can follow her on twitter at @JessicaJFulton, and follow them on @JointCenter. Eunice Owusu is a Council on Contemporary Families Public Affairs Intern and a 2018 graduate of Framingham State University in Sociology with a minor in Political Science.

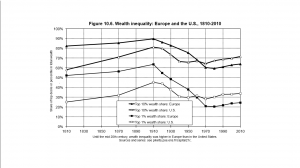

Heather Boushey, Executive Director and Chief Economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, discusses French economist Thomas Piketty’s new book on global economic inequality and spells out its relevance for feminists.

Heather Boushey, Executive Director and Chief Economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, discusses French economist Thomas Piketty’s new book on global economic inequality and spells out its relevance for feminists.

Guest poster

Guest poster