I wasn’t part of this past weekend’s mad AWP melee but I was thinking about how the influx of an estimated 10,000 attendees filled with literary ambition creates its own kind of adrenaline and angst-filled elixir. It led me to dig out a piece I wrote for an online magazine last spring, yet unfortunately, they never ran. I corresponded with several major female poets to ask what their experience of gender bias in the literary world has been. Plus ca change, I want to say, but the irony is that for women publishing, so very little has.

Just before this year’s AWP conference began, VIDA: Women in Literary Arts released this year’s “The Count” which starkly portrayed the woefully small pieces of the literary pie served up by women writers in major literary sources. I wish I could say much was different from last year’s report, but it’s not the case. One thing that is rising, however, is awareness of the gross discrepancies about who is published in the literary world. Here is the article I wrote last year, with excerpts from several prominent writers I was thrilled to correspond with:

Although T.S. Eliot called April “the cruelest month,” the first signs of spring bring the annual celebration of National Poetry Month. This year, however, interest began to blossom early with the February release of “The Count” by the literary organization VIDA: Women in the Literary Arts.

Founded by poet Cate Marvin in 2009 during a moment she describes as an homage to Tillie Olsen’s iconic story “I Stand Here Ironing,” Marvin, while folding her infant daughter’s clothes, began to contemplate why her panel on contemporary American women poets had been rejected for the competitive national Associated Writing Program conference. An email “seemed to blast right out of my head,” she writes, and within months her cri de coeur about lack of gender parity in the literary world had picked up a fierce momentum. A year later, VIDA is thriving, with plans for a conference focusing on women’s writing, and moreover, a community that has the desire to shake up an imbalance that has been tolerated for too long.

The Count 2010 revealed stark pie charts that indict the top literary journals and highly regarded magazines for their abysmal inclusion of women — whether as contributors or authors reviewed or book reviewers. Immediately, both outrage and “it’s about time” comments appeared as some editors went on the defensive about the results. One humbled male reviewer called the study “in many ways a blunt instrument” with the suggestion that breakdown of its statistics would further illuminate the nuances of bias that surface in, as he writes, “the staggering differences between male and female representation.” Meghan O’Rourke on Slate lauds the study but adds, “a task VIDA might usefully take on is a breakdown, by gender, of the genres reviewed and represented.” Shock, debate and denial quickly raged in many literary sources with a mix of defensiveness and admirable get-to-the-bottom-of-this persistence. But, as O’Rourke tackles, the fundamental question behind the thin pie slices served up for women is, Why?

The answer, of course, is complex. The oft-cited information that women enroll in MFA programs at an equal, if not higher, rate than men is clear, as is the fact that more women buy books in the United States, and are likely to be readers. But breaking into the journals and magazines that can “make” a writer’s career by laying a direct pipeline to a high-profile agent or a publishing contract, or can compound the cultural capital of a positive review into a prestigious grant or even tenure-track job interview, seems to be about something else — the tactics of how one gains ground in the po’biz world or becomes part of the g/literati.

As talk swirled around the indisputable net effects of the VIDA stats, attention began to focus on the subtler issues surrounding how ambition and promotion are gendered. Blogosphere debate raged around topics such as how networks of male influence hold impact; the subtle, but real, assumptions behind who deserves a job; how fame is won; as well as the intangible but real sense that putting oneself forward as a writer requires a certain kind of brash ego more often cultivated by men. And while most editors responded with culpable awareness, some offered that the flip solution of tokenism doesn’t solve the root problem.

The topics raised afresh by VIDA, unfortunately, are hardly new. Just four years ago, an essay entitled “Numbers Trouble” co-written by Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young in The Chicago Review targeted gender representation in the experimental poetry world. The two women counted bylines by women within anthologies, journals, major awards and blogs, confirming a rather dismal ratio. The blog site of the venerable Poetry Foundation responded swiftly, in part, trying to parse the social conditions surrounding women and time, caring for children, encouragement of ambition, cultivation of career, and its much-vaunted Poetry Magazine had even commissioned an essay years before (in 2003) trying to root out why women are represented in such unequal numbers. As Spahr and Young write in “Numbers Trouble”: “We are also suspicious of relying too heavily on the idea that fixing the numbers means we have fixed something. We could have 50 percent women in everything and we still have a poetry that does nothing, that is anti-feminist.”

Spahr and Young also counted women’s bylines at a variety of small, independent presses and hardly found parity there, although “University presses are a little more skewed to gender equity.” But even Wesleyan University Press, which they point out is known for publishing mainly women, “has 90 books by men and seventy by women (44 percent); a better number, but far from ‘mainly.'”

I corresponded with four poets of different generations who published with Wesleyan, and they each came back to the idea that it’s not a question of quality that keeps them from being published–it’s systemic bias.

This past week you might have noticed something different around here.

This past week you might have noticed something different around here. This is the fifth and final in a series this week from Girlw/Pen writers on Stephanie Coontz‘s new book,

This is the fifth and final in a series this week from Girlw/Pen writers on Stephanie Coontz‘s new book,  Mama lost her pen today, but she’s working on a post about her current configuration of childcare and work and how things are shifting…soon. Please stay tuned.

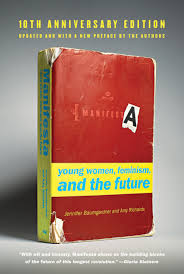

Mama lost her pen today, but she’s working on a post about her current configuration of childcare and work and how things are shifting…soon. Please stay tuned. Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards’ ManifestA turns 10, and an anniversary edition has just been released from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. For a great retrospective, see Courtney Martin’s piece this week at The American Prospect,

Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards’ ManifestA turns 10, and an anniversary edition has just been released from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. For a great retrospective, see Courtney Martin’s piece this week at The American Prospect,