In a recent post titled “Digital Dualism of the Real,” Nathan Jurgenson (@nathanjurgenson) wonders if there are several kinds of digital dualisms and, if so, how we should label them. I am a bit surprised by such a concern as I don’t consider digital dualism theory to be divisible or “splitable,” given that I started to develop it in my own way in France. I have found Nathan’s theory of digital dualism very useful; however, because this new idea of different kinds of digital dualisms appears to me as an unwanted consequence of the recent debate with Nicholas Carr, I would like in this post to help him further develop his theory and make it even stronger. That’s why I will start my reflection here by coming back to Carr’s arguments, in order to deconstruct them in greater detail. Because, unfortunately, I think they all are false.

In a post published on his blog only two days before the Theorizing the Web conference, Nicholas Carr is trying to invalidate the digital dualism critiques coming from the Cyborgology’s blog authors. We can wonder why a Pulitzer Prize nominee author of influential books translated into more than 20 languages is so interested in the digital dualism theory. It is easy to answer that: Carr is clever enough to detect that a new generation of digital scholars is developing very strong ideas. And, because he is targeted by them as a digital dualist, he is compelled to attempt to demonstrate the contrary. But he is wasting his time. What are the main objections of Carr?

Carr’s first objection

The observation that “our reality is both technological and organic, both digital and physical” is banal. I can’t imagine anyone on the planet disagreeing with it. […] Nor can I imagine that anyone actually believes that the offline and the online exist in immaculate isolation from each other, separated, like Earth and Narnia, by some sort of wardrobe-portal.

Mr Carr, it is easy to explain why you cannot imagine it: You refuse to admit that many people do believe such a thing, including yourself. It is absolutely not banal to observe that our reality is both digital and physical, once you consider the reality as made of one unique substance. There is a major difference between conscious, logical judgements and value judgements influenced by the unconscious. Using a logical judgement, everybody can describe reality as made of different aspects, such as digital and physical or whatever, as you do in this quote. But what really creates problems in this debate is that, although everybody is able to logically describe (from the consciousness) the enmeshment of the digital and the material, everybody still fantastically believes (from the unconscious) that the digital and the physical are “separated worlds” or spheres. That’s why, in my #TtW13 presentation, I argued on that digital dualism is mostly a phenomenological issue based on a metaphysical fantasy (more than a fallacy, even if a fantasy is obviously a fallacy).

My point is that there does exist nowadays, in dominant mentalities, a fantasy of the difference between the virtual and the real. It can be described as an ontological value judgement coming from the unconscious and shared by many people, according to which the digital and the physical, the online and the offline, are separated realities or worlds. That’s why Nathan is perfectly right when he states that digital dualism is “the belief that online and offline are largely distinct and independent realities” (the word “belief” is much better than the word “bias” or “tendency”). The Cyborgologists do not simply describe digital dualism as a logical judgement, so please don’t behave as if you had not understood. In my interpretation, they are talking about digital dualism as a psychological fantasy that relies on an ontological value judgement, which is mostly rooted in belief. And, Belief is not Reason.

(I tried to explain where this belief comes from in my presentation when I talked about the “phenomenological violence” of digital revolution. You’ll find more about it in my forthcoming book, Being and Screen: How Technology affects the Way we Perceive [to be published in French in next September]).

Carr’s second objection

We’ve now entered a realm of very fuzzy semantic distinctions. What the terms “worlds” and “reality” actually denote is not at all clear.

Sure! I could not agree more. But, Mr. Carr, cannot you see that those fuzzy distinctions are not scholarly distinctions offered by researchers (Cyborgologists or others); rather, they are popular distinctions coming from the everyday ontology of regular folks? No serious philosopher would admit such a stupid divide between the Real and the Virtual. It is completely opposed to the Western philosophical tradition–from Aristotle to Deleuze–according to which the Virtual is a kind of Real, and not the contrary of the Real. (If you are not familiar with this philosophical tradition, I recommend the (1995) book by French philosopher Pierre Lévy : Becoming Virtual: Reality in the Digital Age).

Ontology is not only an academic affair. Everybody does ontology in their everyday lives, because everybody needs a representation of the world in order to live within it. However, because most of people are not professional ontologists, they have built a popular ontology in order to try understand what’s happening to them into the digital era. This is the origin of the deceptive divide between the Real and the Virtual. That’s why those terms “world” and “reality” seem to you so unclear. Because they are not well-reason concepts; they are fantasies or beliefs from popular ontology.

On the contrary, “digital dualism” is a proper philosophical concept. “Virtual,” “World,” “Reality” are each deceptive names for the same fantasy: the (neo-Platonic) belief in a place that is separate and distinct from our physical place. The concept of digital dualism confronts this fantasy with philosophical reasoning. There is no difference between the real and the virtual, there are no separated worlds, there are no worlds. There is only one reality, one single continuous substance, which is the fundamental principle of what I call now digital monism. And, it is absolutely not banal to promote awareness of this, because most of people have so great desire to believe in digital dualism.

People really do feel a difference and even a conflict between their online experience and their offline experience. They’re not just engaged in posing or fetishization or valorization or some kind of contrived identity game. They’re not faking it. They’re expressing something important about themselves and their lives—something real.

Don’t deny it, Mr. Carr: There does exist a “general and delusional dualist mentality.” That’s obvious. That’s exactly why, as you say, “people really do feel a difference and even a conflict between their online experience and their offline experience.” Yes, I really do feel myself this difference in my own life, but I absolutely don’t feel this difference as a conflict or a problem. And, I think that our kids will be less and less likely to feel this difference as a problem or a conflict. It does not mean that they will stop feeling the difference. The difference will always be perceptible. One century after the invention of the telephone, we still know the difference between the face-to-face presence and the telephonical presence. But we don’t feel it as a problem or a conflict anymore. We know how to enmesh them peacefully. That’s the same with the difference between the digital and the physical: We are learning how to enmesh them peacefully and, very soon, we will no longer feel them as a conflict.

Carr’s third objection

Nature existed before technology gave us the idea of nature. Wilderness existed before society gave us the idea of wilderness. Offline existed before online gave us the idea of offline.

This is a very famous Rousseauian naive illusion. Since Homo habilis started to use stones as tools, more than 2 million years ago, Nature has never existed. Any serious philosopher knows that. I can remember what Prof. Jean-Claude Beaune, my old professor of philosophy of technology in Lyon, wrote in 1972 (!):

The world we are facing, in our most daily experience, is cultural, that is to say technical and technicized in all parts. We have no natural experience of the world and of ourselves. (1)

We never lived in a “state of nature” because Nature has never existed for us, as Humans. Our human world has always been “technologically textured” (2), more or less (and today, more than less). Of course, mountains and rocks are real. But, please, do we live in mountains? Only with technical stuff. Otherwise, we don’t live there. The human lifeworld has always been a techno-Nature.

So, Mr Carr, you have a logical fallacy on your hands: “Nature = Wilderness = Offline.” It is completely wrong. Nature and Offline encompass the presence of humans (and have always technical aspects) whereas wilderness is based on the absence of humans (which therefore excludes any technical aspects). So you cannot refer to the Wilderness in order to give sense to the Offline. Not comparable.

(Nathan also responded very well to this objection by arguing on that “Nature is always a social construction.”)

Carr’s fourth objection

“A mode of human experience is being lost.”

This is absolutely invalid. Techniques always accumulate. Modes of experiences conditioned by techniques are never lost, but just add up, enhancing the possibilities of human experience. More than one century ago, we invented the telephone and it affected our lives as much as digital media do now. This is what Herbert N. Casson said in his early (1910) The History of the Telephone:

What we might call the telephonization of city life, for lack of a simpler word, has remarkably altered our manner of living from what it was in the days of Abraham Lincoln. It has enabled us to be more social and cooperative. It has literally abolished the isolation of separate families, and has made us members of one great family. It has become so truly an organ of the social body that by telephone we now enter into contracts, give evidence, try lawsuits, make speeches, propose marriage, confer degrees, appeal to voters, and do almost everything else that is a matter of speech.

We could say exactly the same today about the digitalization of life. We had not lost the face-to-face mode of human experience because of the telephone. We added it up to our experience possibilities. And we’re doing the same today with the Internet. That’s why I agree with Carr when he admits that, actually, he is afraid :

“We sense a threat in the hegemony of the online because there’s something in the offline that we’re not eager to sacrifice.”

Thank you for admitting it, Mr Carr. You’re afraid by new technology. And that’s because you believe in the logic of substitution of technologies instead of the logic of accumulation.

Why spliting digital dualism theory?

Let’s now go back to Nathan’s post on “Digital Dualism of the Real.” It seems to me that this is an overreaction to Carr’s comments, perhaps because Carr is a famous columnist and writer in the United States (whereas he is known as an alarmist thinker in France)? Nathan says:

Nick Carr, as much as we disagree, has always been right that the terms being used here are less than clear.

As I just explained above, those terms are not academic terms. They are people’s terms, coming from the popular dualist ontology. If those terms are not clear, it is because the popular dualist ontology is not clear. And it is not clear because, of course, it is wrong! That’s exactly why the digital dualism theory is true. So, when Carr said this, he was just giving another proof in favor of digital dualism critique.

Anyway, Nathan says he would like to switch gears. So he reminds us the classic philosophical distinction between the real (what includes existence) and the true (what holds authenticity). He correctly points out that we often use the term “real” to capture both meanings. But he explains that, on the one hand, if you focus on the real as what includes existence, you’re led to an ontological digital dualism critique, only concerned with objective realities, i.e. isolated from subjective concerns of people and of what people think is important/human/deep. On the other hand, if you focus on the real as what holds authenticity, you’re led to some kind of ethical digital dualism, mostly concerned with value statements (i.e., isolated from ontology).

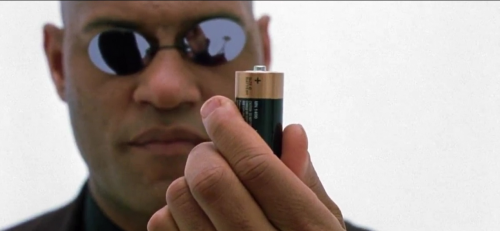

What are the implications of inserting this philosophical dualism within digital dualism theory? I think it is a mistake and not a good solution for the future of digital dualism critique (of which I am a staunch defender from France, following my presentation at the Theorizing the Web 2013 conference). Because, since Plato, ontology has always founded ethics. Only because there are two separated worlds in Plato’s metaphysics can Plato argue on that the philosophers must quit the Cave in order to access the real world. Only because you know that the Conscious and the Unconscious are real can you act as a psychoanalyst in your office. Only because Neo knows that the Matrix is real can he get out from it and change his life. Knowing the truth is the surest way to make value statements and therefore take decisions and actions in your life. It is your idea of the real that determines your actions in life.

Ontology and Ethics are not severable. Just because you refuse to employ the term “real” does not mean that you are not making ontology (and this term is unclear only for Carr). Ontology is not a sham. Ontology is the foundation. “Cultural value statements based on the idea that the on and offline are distinct rather than enmeshed” are more deeply based on ontological fantasies and beliefs. Digital dualism cannot ignore that. When Nathan says:

Thus, digital dualism is the tendency to see the digital and material as too distinct, rather than enmeshed,

he is still discussing ontology. Adding the “too” does not (and cannot) change anything. It is just impossible “to place ontology largely on the back-burner.” Because it always comes from the back to the front with more power, as fantasies do from our unconscious life to our consciousness. Why dismiss ontological digital dualism? Confrontation is inevitable. We must live with it and clarify it again and again. Everyday ontology makes everyday ethics. And, professional ontology makes professional ethics. Even with regards to technology.

I do agree that the goal is not to make ontology because it’s fun to make ontology. The goal is to change mentalities and turn people into digital monists, so that they can act differently with digital media and stop making fallacious statements such as “these kids with their Facebooks are trading reality for the virtual!” When they change their ontological assumption about what is real changes, new value statements, new decisions, and new life experiences–enmeshing more and more the digital and the physical–will be possible.

So, Mr Carr and all digital dualists should wonder this: When our kids become adults, following years and years spent on Facebook and video games, which ideas will they admit as true: digital dualist or digital monist?

I’m Stéphane Vial. I’m a Digital French Theorist at Technophilosophy. And I’m on Twitter [@svial].

This post was directly written in English without any help from my usual translators : please forgive tactlessness. It can be offered to Cyborgology readers thanks to the great editing work from PJ Rey. My warm thanks to him, that’s the way I like sharing ideas across oceans in the age of the Internet.

Notes

1. Jean-Claude Beaune, La technologie, Paris : PUF, coll. “Dossiers Logos”, 1972, p. 5.

2. Don Ihde, Technology and the Lifeworld, Bloomington and Indianapolis : Indiana University Press, 1990, p. 1.

Comments 30

Digital Dualism and Lived Experience: Everyday ... — April 9, 2013

[...] [...]

quiet riot girl — April 9, 2013

Hi Stephane - a very thought provoking piece (and thanks PJ Rey too for the 'editing'! ).

Rather than respond directly to any particular words, of Stephane, Nathan, Nick Carr (do we have that 'great men' of history issue raising its ugly head again @phenatypical ?) I want to insert another word beginning with D:

Discourse.

I am trained in discourse analysis and my Phd study involved uncovering and examining some discourses and discursive practices around the 'creative industries'.

So, it's possibly not surprising the way I have come to look at 'digital dualism' is as a discourse.

I don't think the employment of discourse is a 'fallacy'. So when people resort to 'digital dualist' discourse, and they often do, I don't think of them as being 'wrong' or 'false'. It is just a response to our contemporary world and a way of discussing/presenting that world that 'makes sense' in certain contexts to certain people. I believe people are capable of (and probably can't help) drawing on both digital dualist and non-dualist discourse in different situations and different times.

I wonder if Mr Carr and others might be objecting to being labelled as certain types of people, people who lack the intelligence of, say, cyborgologists, people who use 'digital dualism' and who think 'fallacies' are 'true'? When maybe Carr and others do have a more complex understanding of this complex world we live in but have been 'caught out' for employing a simplistic but useful (and yes potentially damaging) discourse?

I think some of us could be 'caught out' in similar ways if someone was to carefully analyse our texts.

Because discourse is impossible to avoid when expressing oneself.

And , if we use Foucault's approach to the 'truth' or the 'true' we start to see these concepts as very nebulous. As are 'right' and 'wrong'.

I still believe and have said so to Nathan and others a number of times that 'digital dualism' is a great concept. But maybe now I don't think it is necessarily useful to reveal a 'fallacy' but rather to examine a 'discourse'. And a discourse that is powerful and interesting and difficult to escape, even if we might be the person who first identified it!

- QRG

Digital Dualism and Lived Experience: Everyday ... — April 10, 2013

[...] In a recent post titled “Digital Dualism of the Real,” Nathan Jurgenson (@nathanjurgenson) wonders if there are several kinds of digital dualisms and, if so, how we should label them. [...]

Stéphane Vial — April 10, 2013

We can try to understand better each other, I can see some misunderstandings in your comments.

1. What do you think about my considerations above on the difference between a "Discourse" and a "Feeling"? I made it for you, in order to make my argument clearer, you should pay more attention for it, I would be glad to hear you on that. Cannot you see that, when "people express themselves through language", they add fantasies (in a Freudian sense) to their discourse (which are feelings)? My background is both philosophical and psychoanalytical and I consider all discourses as always rooted in uncouscious fantasies.

2. About the true and the false of Discourse, I think we are not talking about the same thing when we say Discourse. I'm talking about Scientific Discourse, because I'm a Scholar and a Researcher, and not a Writer (as Carr), a Believer (as a Creationist), a Priest or whatever you want. Considering Discourse as a Scientific Discourse, Discourse is necessarily a matter of true or false, and always have been. If you don't agree on that, then you have against you Aristotle, Euclid, Stoics, Avicenna, Averroes, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Kant, Frege Husserl and many others! Good luck because those guys existed a few thousand years ago too :)

3. Last point: actually, we must not be impressed by thousands of years of ideas. Aristotle was not, Descartes was not too, Kant was not too, Freud was not too. None philosopher or thinker in the past had an experience of the digital. We are the first generation of scholars trying to tackle the digital.

Nick Carr — April 10, 2013

>>I wonder if Mr Carr and others might be objecting to being labelled as certain types of people, people who lack the intelligence of, say, cyborgologists, people who use ‘digital dualism’ and who think ‘fallacies’ are ‘true’? When maybe Carr and others do have a more complex understanding of this complex world we live in but have been ‘caught out’ for employing a simplistic but useful (and yes potentially damaging) discourse?<<

Well put, QRG. The popular use of terms like "online" and "offline" shouldn't be taken as indicating a rigid "zero sum" view of existence. Those terms are, as you suggest, a useful means of distinguishing between modes of experience that people view as different (and sometimes impinging on each other) without being mutually exclusive.

As to Monsieur Vial:

1. "You refuse to admit that many people do believe such a thing, including yourself."

Critical rigor, not to mention intellectual honesty, would require that you back up such statements with some proof. So until you can point to the actual texts where I and others announce our belief "that the offline and the online exist in immaculate isolation from each other," I will need to treat this point of your polemic as frivolous posturing. I realize that, in again asking for close readings of actual texts, I may well be beating a dead horse, but so be it.

2. "But, Mr. Carr, cannot you see that those fuzzy distinctions are not scholarly distinctions offered by researchers (Cyborgologists or others); rather, they are popular distinctions coming from the everyday ontology of regular folks?"

That's been my point all along, actually. So, yes, I can see it.

3. "Since Homo habilis started to use stones as tools, more than 2 million years ago, Nature has never existed."

If you take a close look at what I actually wrote - "Nature existed *before* technology gave us the idea of nature." - you will discover that it is pretty much identical to what you wrote. So I'm not sure we disagree here.

4. You quote me as writing, “A mode of human experience is being lost.” Actually, if you look back to my post, you'll find that I did not write that. That's a quote from Michael Sacasas. You then argue, "Modes of experiences conditioned by techniques are never lost, but just add up, enhancing the possibilities of human experience." That's highly dubious. You're certainly free to take the optimistic view, but to argue that technology simply piles new possibility atop old possibility is a bit silly. Of course there are loses to go along with the gains. Do people have the memory skills they had pre-alphabet? Of course not. Do people in contemporary society have the navigational skills that people in ancient hunter-gatherer societies had? Of course not. As to the telephone making us members of "one great family," I note that that was written just before the outbreak of the First World War.

You quote my sentence, "We sense a threat in the hegemony of the online because there’s something in the offline that we’re not eager to sacrifice.” And you then write, "You’re afraid by new technology." Surely you're twisting my words in a grotesque way. And then you write, "And that’s because you believe in the logic of substitution of technologies instead of the logic of accumulation." I believe in neither "logic." Progress is a complicated process that involves both substitution and accumulation. You're the one guilty of oversimplification here, not me. And, unfortunately, it's an oversimplification, bordering on utopianism, that underpins your entire argument.

Nick

Stéphane Vial — April 10, 2013

Mr Carr,

Thank you for responding. It is difficult to target someone in a blogpost as I did there. Hope I'm not tactless. I'm just excited by ideas.

1. You know that I cannot provide you any irrevocable proof of this statement, if you mean by proof some explicit quote of you saying that you do believe in digital dualism. As a philosopher, I'm tracking underlying assumptions, and when I read your post, I thought I could detect this belief in the fact that you don't admit the interest of "digital dualism denialism". Why? I think that to deny the separateness between the offline and the online is useful and necessary. Because they are not separated. They are just different. And that matters in order to stop believing in the so-called danger of Facebook and other online experiences. Because ontology produces ethics, and so on, as said in the post.

2. Good. That's why, for me, digital dualism denialism is necessary in order to dismiss "those fuzzy distinctions". Because those fuzzy distinctions are typically dualist. So if you admit that dualist distinctions are fuzzy distinctions, why not admitting the interest of digital dualism denialism?

3. If you take a close look at what I actually wrote - "Nature and Offline encompass the presence of humans (and have always technical aspects) whereas wilderness is based on the absence of humans (which therefore excludes any technical aspects)" - perhaps you will understand me better: Nature existed before technology gave *us* the idea of nature but *we* ("us") had never existed before technology! So we had never known Nature (considered as mere Wilderness).

4. It is true that, in your post, “A mode of human experience is being lost" is a quote from Michael Sacasas. But did you quote it because you don't agree with it? English is not my native language but it seemed to me that you quoted it in order to point out that digital dualism denialists "avoid seeing" something. Anyway, of course there are loses to go along with the gains. But alphabet still does exists and the telephone too. Major innovations are not lost but added up. That's what I meant. And the Internet is a major innovation, I think you agree on that.

5. You're right on this: "Progress is a complicated process that involves both substitution and accumulation". In order to present my main argument in this post (which is about digital dualism), I focused only on accumulation. My idea is actually much more complex. It is close to Kuhn's paradigm shift. In a word, I think that "technical revolutions" are based on a few major technologies which are something like a "technical paradigm". Those paradigms are evolving in history following a logic of substitution (steam engine mostly disappeared) while some other main innovations are following a logic of accumulation (alphabet, printing, Internet…).

I realize it's very hard to discuss about all that in an another language than my native language. It prevents me to explain correctly details and shades of difference, giving you the impression of "oversimplification". I'll try not to forget that in the future and will not write more in this too long comment.

At least, I hope I could respond correctly above about the main point: the *digital dualist belief*. That was the main focus of this post. My forthcoming book will be a better respond.

Thank you.

Stéphane.

quiet riot girl — April 10, 2013

I think the notion of 'failing to see' something is interesting.

I suspect we all fail to see some things by taking positions and choosing our sides and looking at the world in certain ways from certain vantage points.

What I would like to *see* is more rapprochement in terms of accepting there is no viewpoint that is 'all seeing' - except maybe 'God's'. And we're not the types to believe in Him right?!

To be honest I have found some of the recent cyborgology posts attempting to 'define' the non-dualist perspective using diagrams and jargon quite soulless. Isn't this confusing changing environment something that may resist pigeonholing? I hope so!

Maybe it is the 'digital dualists', ironically, who have accurately conveyed some of the awe, fear, disconcertion that must inevitably come with fast technological/social/economic change? They may have then reached overblown conclusions but I am inclined currently to respect some of their - yes - feelings.

nathanjurgenson — April 13, 2013

Stéphane, thanks for the terrific thoughts!

I very much agree that ontology and ethics are very related projects, and I did admit as such in my post you are responding to here. However, for practical reasons, different conceptual angles of a larger single project can be tackled independently--and always with the goal of unifying them when possible. In my estimation, much of the digital dualism debate was getting too concerned with atoms and bits and not explicitly discussing the moral/ethical/political matters. As such, I want to balance the discussion, not to create division but for better unification, a goal we share. I have found splitting and naming the various (interlinked!) trajectories of digital dualism critique conceptually and strategically useful.

One more point: the philosopher in me finds most intuitive the idea that values are built on ontology (e.g., dismissing people on phones as less-human robots is a consequence of downplaying the embodiment, social, material in digital connection). Correct me if I am wrong, but this is the logic I find implicit in your posts (but please correct me if I am wrongly putting words into your mouth here). However, the sociologist in me instead assumes that, for many, the ontology (I know I am using that term a bit messy in this comment!) is more likely a consequence of the ethics (e.g., in order to justify the belief that others are less human, one develops a dualist ontology). Logically, this isn’t very satisfying, but may very well be more common in practice. As such, it might very well be that convincing people that the digital dualist dehumanization happening here is ethically wrong might be the more convincing route to change underlying and unconscious ontology than the reverse (asking people to change their ontology in order to change their ethics). Did that make any sense?

But to be clear, I think we only slightly disagree here on tactics, and not at all on the conceptual issues. And I say “slightly” because I do agree ontology/epistemology/ethics are all wrapped up and best integrated; I just think to do so we need to put more energy in the ethics side of things to make this happen.

Hope all is well in France!

Digital Dualism and Lived Experience: Everyday ... — April 13, 2013

[...] RT @Soc_Imagination: Digital Dualism and Lived Experience: Everyday Ontology Produces Everyday Ethics http://t.co/FTUmZWWfRG [...]

Week in Review – 19 April 2013 | USMA Library Beta Blog — April 19, 2013

[...] “One century after the invention of the telephone, we still know the difference between the face-to-face presence and the telephonical presence. But we don’t feel it as a problem or a conflict anymore. We know how to enmesh them peacefully. That’s the same with the difference between the digital and the physical: We are learning how to enmesh them peacefully and, very soon, we will no longer feel them as a conflict.” – Digital Dualism and Lived Experience: Everyday Ontology Produces Everyday Ethics » Cyborgology [...]

Internet detox promotes the myth of web toxicity – The Guardian – internet news | Fonte English — May 6, 2013

[...] up digit in visit to undergo the another truly. Academics intend to this simulated star as “digital dualism“, coined by the sociologist Nathan Jurgenson who defines it as “the belief that online [...]

Internet detox promotes the myth of web toxicity – The Guardian – internet news — May 6, 2013

[...] up digit in visit to undergo the another truly. Academics intend to this simulated star as “digital dualism“, coined by the sociologist Nathan Jurgenson who defines it as “the belief that online [...]

shtecker.com | Internet detox promotes the myth of web toxicity — May 7, 2013

[...] give up one in order to experience the other truly. Academics refer to this false binary as “digital dualism“, coined by the sociologist Nathan Jurgenson who defines it as “the belief that online [...]

ArtSmart Consult — May 23, 2013

Stéphane:

First, "digital" is an oversimplification of virtual reality. Virtual reality consists of both analog and digital information. More accurately, digitizing information is only one way of processing analogue information. Fuzzy logic is only made crisp by means of simplification and often oversimplification. Your use of the word "digital" is more problematic than digital dualism.

Second, virtual reality is a part of physical reality, but is different in nature because it doesn't contain the same combination of elements or particles. That is a fact. Virtual reality is to physical reality what oxygen is to water. Information processing with physics will never be as predictable as physics without information processing. If that's what you call digital dualism, then digital dualism is factual.

It appears your only problem with digital dualism is a fear that it will lead to dismissing the virtual reality part of physical reality as "not real." That would be a rational fear. But attacking what you think is a false dichotomy will not advance the cause. It's not a science problem. It's a language problem.

Week 7 Discussion | New Media & Communication — October 6, 2014

[…] Digital Dualism and Lived Experience: Everyday Ontology Produces Everyday Ethics by Stéphane Vial. […]

Miss Emma Nicole — October 10, 2014

[…] would have to agree with this to some extent, but I lean more towards the contradiction of Vial in Digital Dualism and Everyday Experience. Vial uses the term digital monism to express his disagreement that we exist in two different […]